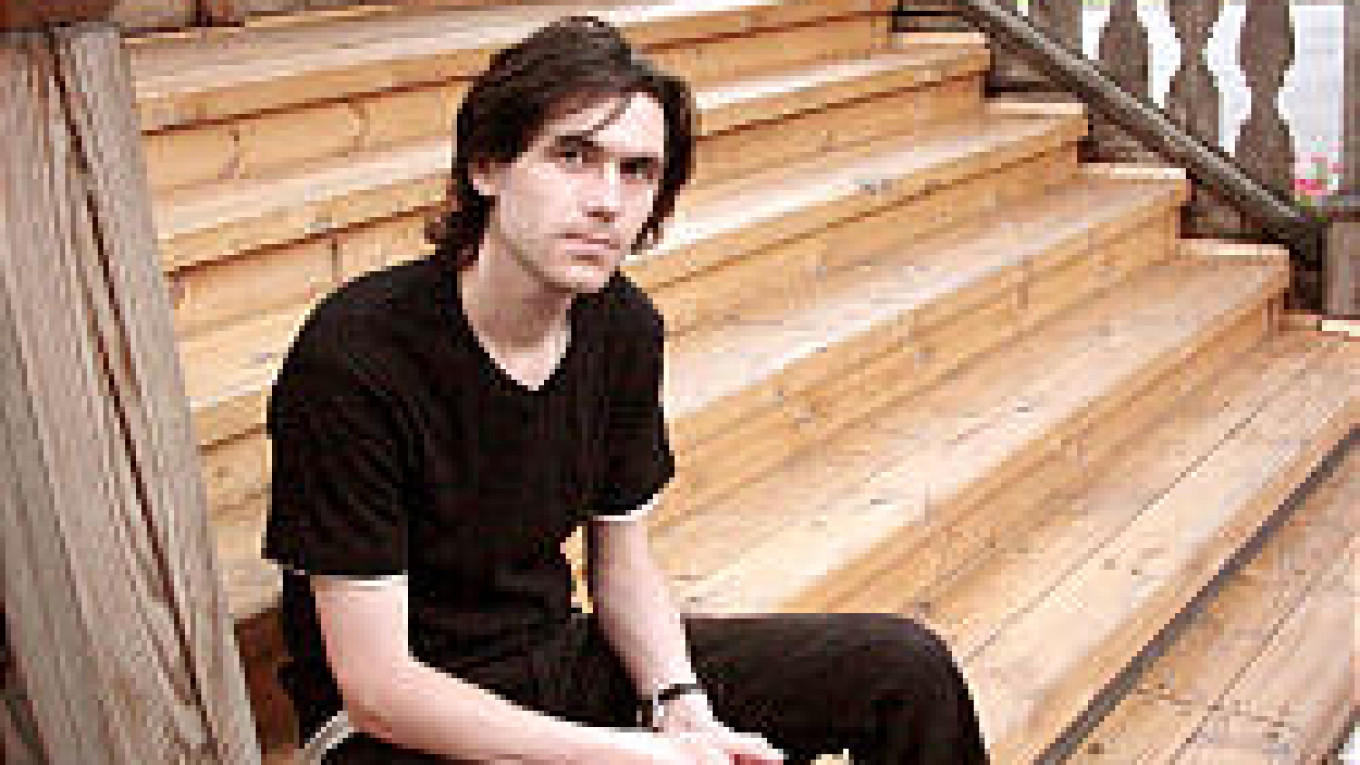

"The situation with drugs is terrible. ... For me, the song was a chance to do something [about the problem], but in a funny format," said Denis Alexandrov, the man behind "Stop Narkotix!," an oddly powerful anti-drug song with nonsense lyrics.

The song, which Alexandrov sings as "Doctor Alexandrov" in a made-up language that is a mix of Latin, Italian, German, English, Russian and French, tells the story of young Pedro, who falls in love with a girl while under the influence of drugs. Alexandrov provides a simultaneous voice-over translation into Russian.

"Je suis la la del country Pedro tarantas/Garanto damages furtu a pas il caballero/Jurago ambraziro je vrai smokin' cannabis," he sings, providing the following spoken translation:

"He was an ordinary boy from a Russian village. His name was Pedro/He fell in love with a local girl/But he was afraid to tell her of his love."

"I had the idea to tell some kind of medical story, but it turned into something like a film, where one man sings and another provides translation," said Alexandrov, who intended the song's preposterous translations and bewildering combinations of words from several languages as a reference to the badly dubbed foreign films that are common fare on Russian television and in theaters.

"For doctors, the song was easy to understand since it's full of Latin medical terms. Plus, it gives a stupid Russian translation for comical effect," said Alexandrov, 27, who wrote the song while still a medical student in his native Irkutsk in 1995.

"And now he sorry 'cuz he's impotento," for example, is translated as "A horrible fate has befallen Pedro -- he's blind."

The song's end is simple, if a bit shocking: Pedro's beloved gives birth to a baby with birth defects (which the Russian language lyrics blame on the lovers' cocaine use) after Pedro discovers that he has become impotent.

"Goodbye narkotix, drugs in uno momento/Stop narkotix, narcomano stoppo!" Alexandrov sings.

"Stop Narkotix!" might have remained a private joke among Alexandrov's medical-student friends if the young doctor hadn't moved to Moscow to begin his career. Alexandrov found work as an X-ray technician at Moscow's Sklifosovsky Institute, the city's largest emergency-care facility.

"Sklifosovsky is a real school of life. I've seen everything there, and now it's difficult to shock me," said Alexandrov, who said a typical night shift at the hospital would have seen him treating an average five or six knife wounds.

While working at the hospital, Alexandrov wrote songs in his spare time, sending tapes to radio stations and record labels. It was "Stop Narkotix!" that got him into rotation on popular FM music station Nashe Radio. The song spent a month on the station's list of hits, finally climbing to No. 1.

But his newfound popularity on the radio didn't save Alexandrov from losing his job at the Sklifosovsky Institute this September -- his Moscow residency permit had expired and the hospital was forced to let him go.

"I was sad, but I understand that music and medicine are separate things," said Alexandrov, who recently released his debut album, also called "Stop Narkotix!"

Alexandrov, whose parents are also doctors, avoids drawing comparisons between himself and another Russian doctor-turned-writer, Anton Chekhov. Instead, Alexandrov likens himself to deceased doctor-turned-revolutionary Ernesto Che Guevara.

"I respect him a lot. The man was able to start a fight against an entire society," said Alexandrov, who dedicated a song to Guevara on his album.

Nevertheless, Alexandrov said that he's not ready to follow in the footsteps of Guevara.

"I haven't grown up enough yet to write prescriptions for society," he said.

Doctor Alexandrov performs often at local venues. See future events calendar listings for information about upcoming shows.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.