Any discussion of who controls Russia typically focuses on the ruling tandem and the differences between the two leaders’ public statements and political positions.

Often, that discussion widens to include officials who were Putin’s friends or colleagues during his St. Petersburg days, members of the siloviki and others who came to prominence under St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak. Sociologist Olga Kryshtanovskaya, director of the Institute of Applied Politics, has written extensively about how most senior officials working under Prime Minister Vladimir Putin and President Dmitry Medvedev have come from the Federal Security Service, armed forces, law enforcement and other siloviki structures.

But this discussion does not fully answer the question of how the elite are perceived by Russians and how stable the social order in the country is. We know the attitude of society toward the president, prime minister and political parties, but we know little about what the people think about the ruling elite.

In the 1990s, a crisis of legitimacy applied exclusively to the business elite who had accumulated enormous wealth by privatizing former Soviet government assets. The word “oligarch” became a pejorative term to denote the nouveau riche who most Russians felt had illegally seized enormous wealth and acquired unwarranted political influence.

Nevertheless, even those who sincerely hated President Boris Yeltsin, Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar and Anatoly Chubais, who headed the privatization program, never questioned their political legitimacy. This is because Yeltsin came to power in a landslide victory in the 1991 election and won a hard-fought victory over Communist leader Gennady Zyuganov in the 1996 election. In 2000, Putin triumphantly won the last relatively free election on a wave of popular enthusiasm and the expectation that he would bring order and rapid economic growth to the country.

But in the 2000s, the authorities seriously undermined their legitimacy. Putin’s run for re-election as president in 2004 was a showcase of political manipulation and abuse of Kremlin administrative resources. During the 2007 State Duma elections, single-mandate districts were eliminated and the authorities refused to register numerous opposition parties. Elected governors were replaced by a system in which Moscow appointed its own loyal servants. In addition, mayors of most large cities were effectively replaced by city managers, who are appointed by the Kremlin and are accountable to Moscow, not the people.

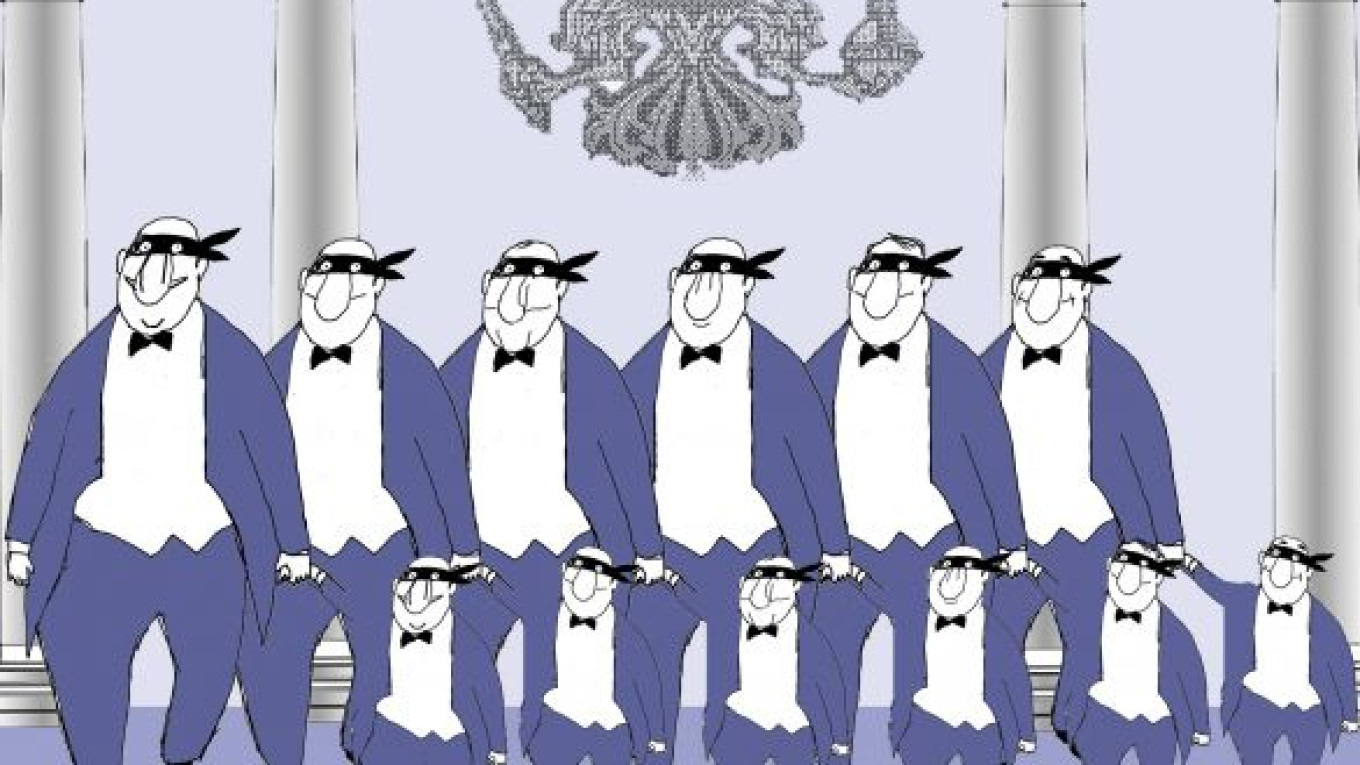

Putin has built a power vertical for himself that is staffed with servile bureaucrats. But in the eyes of the people, that vertical consists of irresponsible and corrupt officials. The people view their relationship with government officials as adversarial — “us versus them.” The people have no say in the way the state is run.

Moreover, members of Russia’s ruling elite are attempting to pass on their power to their children to create a self-perpetuating “bureaucratic aristocracy.” For example, Sergei Matviyenko, 38, the son of? St. Petersburg Governor Valentina Matviyenko — a Kremlin favorite who is slated to become the next speaker of the Federation Council —? has achieved mind-boggling success in banking during his mother’s reign. Deputy Prime Minister Sergei Ivanov’s son Sergei Jr., 31, is the chairman of Sogaz Insurance, which is closely affiliated with Gazprom. Ivanov’s other son, Alexander, 34, is a top executive at Vneshekonombank. Andrei Murov, 41, son of Federal Guard Service director Yevgeny Murov, heads Pulkovo Airport. Denis Bortnikov, 37, son of Federal Security Service director Alexander Bortnikov, heads the VTB North-West bank. Dmitry Gryzlov, son of Duma Speaker Boris Gryzlov, works for the Dar foundation that has close ties to businesses run by Putin’s friends. Anastasia Misharina, daughter of Sverdlovsk Governor Alexander Misharin, runs a large real estate and timber business in the region.

There are thousands of these types of examples. Having amassed significant fortunes under the patronage of their influential and powerful parents, don’t be surprised if within five or 10 years many of these privileged sons and daughters enter politics and occupy key positions at the pinnacles of federal and regional authority — all in an effort to continue their “family businesses.”

But by seizing power and wealth through murky deals that are not subject to public scrutiny, the business and political elite alienate themselves further from the people.

This is risky business. They may think they can hide from the people forever in their luxurious villas with hundreds of bodyguards and an entire army on their side. But, then again, so did former Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak and former Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and their cronies, to name only two recent examples of the thousands that history has to offer.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio and is a co-founder of the opposition Party of People’s Freedom.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.