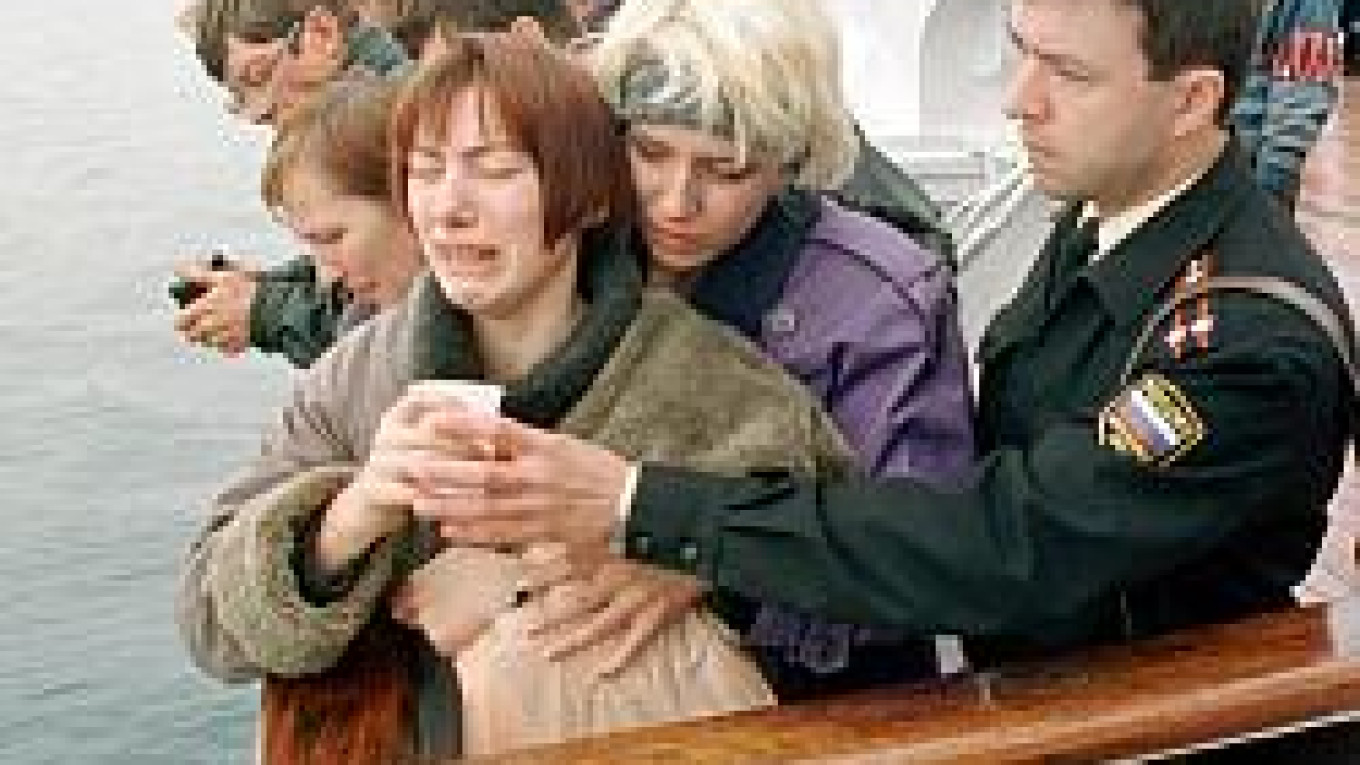

"I know it isn't nice to say this, but I couldn't stop thinking why my husband was not rescued," Gadzhiyev said, her voice throbbing.

"I saw on television how the wives of the rescued Priz crew embraced their husbands. If only I could, I would also hug mine warmly, tightly," she said.

The Kursk sank during a war game in the Barents Sea when a powerful explosion ripped through the nuclear submarine at 11:28 a.m. on Aug. 12, 2000. According to investigators, fuel leaking from an outdated torpedo exploded, causing other torpedoes to detonate.

The military located the Kursk 17 hours later at a depth of 109 meters, and it brushed off foreign offers to help for six days, insisting that it could deal with the accident on its own.

President Vladimir Putin remained on vacation in Sochi for four days, while a shocked nation slowly lost hope and grew resentful toward the authorities.

At least 23 of the 118 sailors survived the explosion and waited for rescuers in the rearmost, ninth compartment of the submarine. Prosecutor General Vladimir Ustinov has said they lived only eight hours after the explosion -- the exact amount of time that it took a Norwegian rescue team to get inside the ninth compartment when the Navy finally sought assistance on Aug. 20.

But military technicians told a commission that investigated the sinking that they detected an SOS signal being tapped inside the submarine as late as 11:08 a.m. on Aug. 14, two days after the sinking.

The Kursk was retrieved 14 months after it sank, but its first compartment, where the blast occurred, was sawed off and remains on the seabed.

Mamed Gadzhiyev, an engineer from the Dagdiezel torpedo-building plant, was one of three submariners whose bodies were not found in the wreckage. He is believed to have been near the exploding torpedoes.

As with every close relative of the Kursk's perished sailors, his family received state compensation above and beyond what families of other dead servicemen had ever gotten. His widow, Safinat, said she received a three-room apartment in Moscow and a two-room apartment in the Dagestani town of Kaspiisk, where the Dagdiezel plant is located. Her two daughters were accepted without the mandatory entrance exams into the prestigious Moscow State Institute of International Relations and Moscow State University, respectively.

Families of the Kursk victims have moved from the northern city of Vidyayevo, where the sailors had been stationed, to settle in the cities where the retrieved remains of their loved ones were buried.

AP Kursk crew members standing on the deck of the submarine during a naval parade in Severomorsk on July 30, 2000, 13 days before the vessel sank. | |

In Moscow, a service will be held at the Church of the Resurrection at Serpukhov Gates, and relatives will visit sailors' tombs at the Vostryakovskoye, Nikolo-Arkhangelskoye and Perepechinskoye cemeteries.

Acting Navy Commander Vladimir Masorin will attend a ceremony near a monument to Kursk victims on the square in front of the Central Museum of the Armed Forces.

Viktoria Stankevich, whose 26-year-old son Alexei was the medical officer on the Kursk, said she would commemorate the fifth anniversary at home with her family in St. Petersburg.

Stankevich said that watching the mini-submarine crisis had forced her to relive a five-year-old nightmare. "For me, it was all the same. I did not sleep for two nights and was praying all the time," she said. "I wanted to hope that those men would be saved, but it was so hard after my own experience."

She said that every time August rolled around with its seasonal naval exercises, she felt overwhelmed with worry and fatigue.

"Every time I see naval officials repeat the same mistakes again and again after the Kursk. And they failed to rescue nine men from another submarine two years ago," she said, referring to the sinking of a decommissioned K-159 submarine as it was being towed in the Barents Sea on Aug. 30, 2003.

Stankevich also received an apartment from the Defense Ministry, but the cash compensation, equal to what her son would have earned over 10 years, went solely to his widow.

"It looks like mothers are not close-enough relatives," she said, bitterly.

Compensation also came from a charity fund, which accumulated donations from all over the world, divided the money into 352 equal shares and handed it out to close relatives.

Controversy, however, continues to swirl over how the money was used. About 15 percent of the fund's more than 100 million rubles ($3.5 million) has been taken by Northern Fleet officials and funneled to private and municipal firms in Vidyayevo, said Boris Kuznetsov, a lawyer who represents the interests of 55 Kursk families.

"The bank account for the donations was opened by the Northern Fleet, and the money was spent with the consent of naval officials," Kuznetsov said, producing a notarized copy of an order by then-Northern Fleet Commander Vyacheslav Popov that appointed his deputy, Vladimir Dobroskochenko, to head the commission that managed the money. No relatives of the Kursk victims were listed among the commission members in the order, dated Aug. 22, 2000.

The federal Audit Chamber reviewed the fund's books in December 2000 and concluded that the money had been spent properly.

But Kuznetsov said that millions of rubles were directed to Vidyayevo companies for what was described in an official account of expenditures as construction and renovation works.

"I myself donated money to this fund twice and wanted it to be passed over to the relatives of the deceased. What I didn't want was my money to be used to finance the renovation of a cafe in Vidyayevo," Kuznetsov said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.