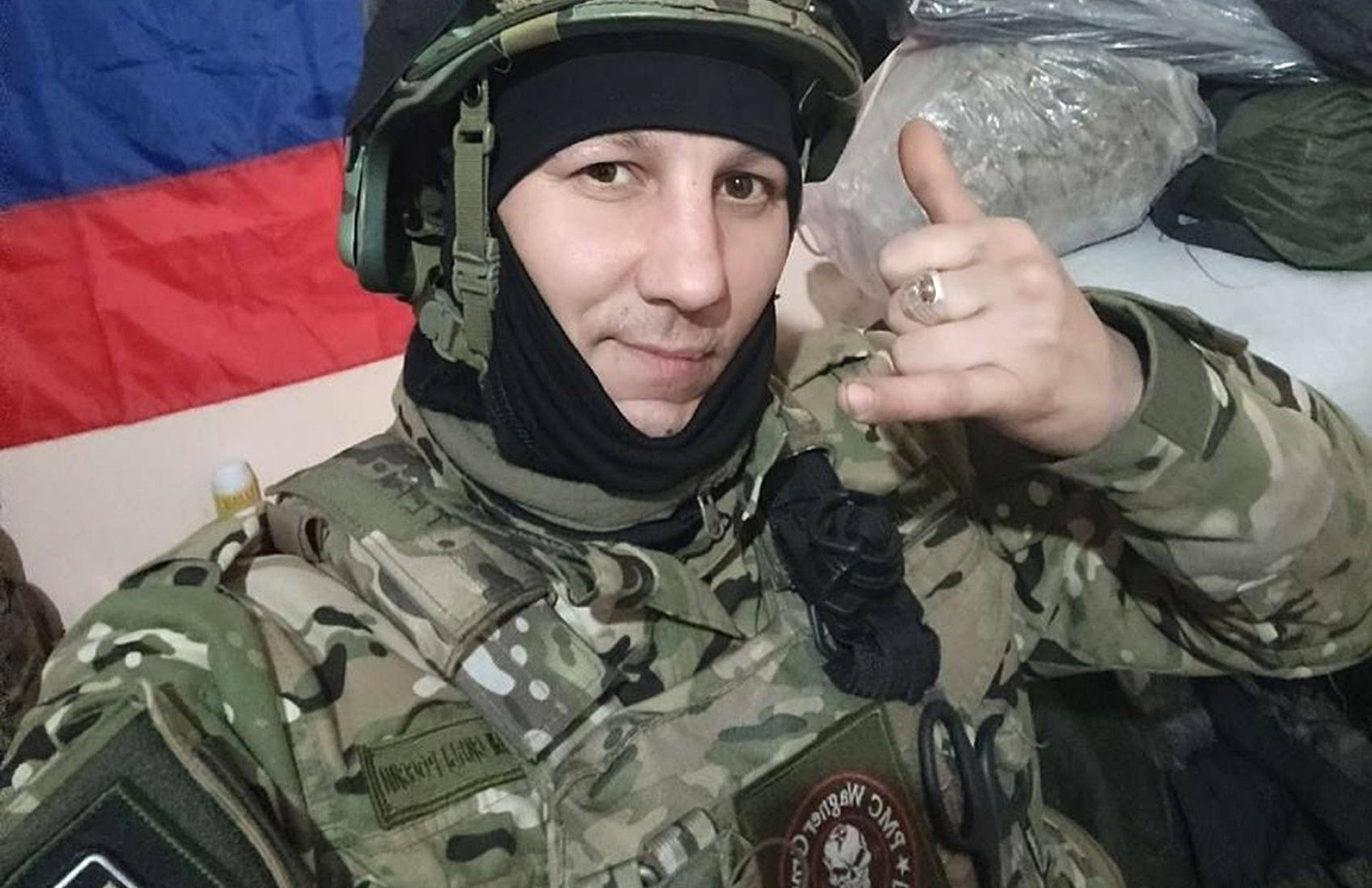

Alexander Platov was in prison for murdering his wife when an unexpected opportunity arose. In 2022, he was recruited into the Wagner mercenary group to fight in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in exchange for a pardon. Six months later, he was a free man.

Unable to reintegrate into civilian life, Platov signed a new contract with the Defense Ministry and returned to the front at the end of 2024. But this time, the former mercenary and his fellow ex-convicts were treated as expendable.

After surviving a suicide assault and sustaining severe shrapnel wounds, Platov shared his story with The Moscow Times.

While The Moscow Times could not independently verify all of Platov’s claims, reporting by exiled media and Russian and Ukrainian sources corroborates some of the details of his account.

The Defense Ministry did not immediately respond to The Moscow Times’ request for comment.

"Life on the outside was hard. I’m a f***ing convict, everyone knew I was in jail several times. Plus, I’m known as someone who likes to drink. I thought I’d be seen as a hero [after fighting in Ukraine], but they looked at me like I was a piece of trash," said Platov, 35.

Born in the late 1980s into a poor family in Ulyanovsk, a city on the Volga River, Platov first broke the law at 17.

"I was jailed for car theft. Eight years. Then I got married. She cheated. I stabbed her. Thirteen more years. That’s where Wagner came in," he said.

In October 2022, Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin landed in his prison yard by helicopter to personally recruit inmates.

"We didn’t take him seriously,” Platov recalled. "I talked back. Then the screws [prison guards] pulled me aside. Uncle Zhenya [Prigozhin] grabbed my ear and said, 'Join Wagner or rot here.' You know, in jail, the convicts were ready to do anything to get out. I joined for freedom too, and the money was good, but I intended to wash my sins away with blood and sweat."

Yuri Borovskikh, a human rights activist from the Russland hinter Gittern (Russia Behind Bars) NGO, said Prigozhin recruited around 50,000 inmates into his Wagner Group during the invasion. Since taking over convict recruitment from Wagner in early 2023, the Defense Ministry has signed up over 100,000 prisoners, he said.

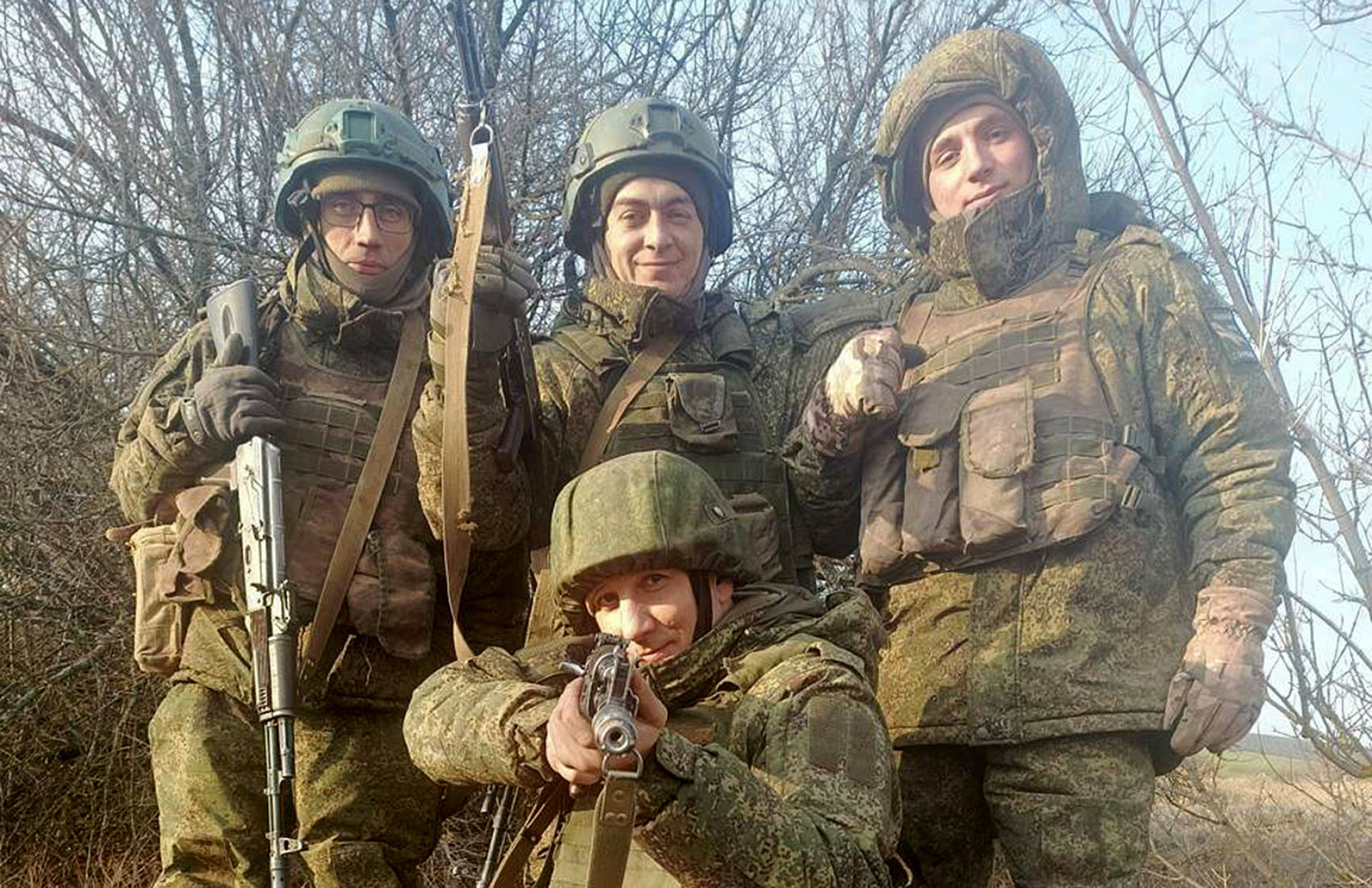

As a Wagner fighter, Platov led a reconnaissance team in Bakhmut.

"I got a silver medal for bravery. From Putin. Imagine that — after two serious convictions. They gave me veteran status. When I came back, I bought a house and got a job, but nobody respected me. People thought I got out just to save my ass and that I bought the medal. So I went back to the draft office and signed another contract — to ‘defend the Motherland’ — or so I thought.”

Borovskikh said people like Platov suffer from compounded trauma. Many reoffend, return to prison and sign up for military service again.

After signing a contract with the Defense Ministry, Platov was deployed near the Ukrainian stronghold of Pokrovsk, where he led a storm group under the 110th Motor Rifle Brigade.

"The Defense Ministry tossed us into this militia like dogs. On paper, it’s the spetsnaz. In reality, they’re sending ex-cons and Chechnya vets. No retreats, no vacations. Maybe [you’ll get one] in two years, if they find your skeleton and identify it," he said.

The treatment Platov described is similar to how newly recruited convicts are handled today. According to Borovskikh, military contracts for convicts now last until the end of the war, and men who sign them have virtually no rights.

"Several penal battalions exist, like this brigade or Storm Z. Most have no families. Their lives are entirely in the hands of their commanders. Those with experience may be useful. The rest? Just meat for assaults," Borovskikh said.

Platov said he believes the 110th Brigade exists in part to “punish” former Wagner fighters.

"There are no real Wagner guys here, just ex-cons, the leftovers. If the real Wagner units came back from Africa or Belarus, Ukraine would be f***ed. Russia would be f***ed too,” he said. “The only thing they gave us was a rifle. Everything else, from underwear to helmets, we had to buy ourselves. Our salaries, ranging from 210,000 to 250,000 rubles ($2,300 to $2,750), get eaten up by food, gear, everything. You survive however you can."

Platov said the brigade made no progress near Pokrovsk. His first mission was to capture the village of Zelene Pole, which his platoon managed to do. Then came rotation.

“They sent in replacements: naval infantry. Contract soldiers from the Black Sea Fleet. The fleet doesn’t even exist anymore. Twenty-five ships sunk,” he said. “One marine hadn’t held a rifle since his oath ceremony 20 years ago. They told him he’d be guarding f**king kindergartens in Donetsk.”

Instead, he said, the marines were thrown into the frontline forests with only basic assault rifles and two magazines each. Soon after arriving, an American Bradley fighting vehicle approached, opened fire at 200 meters, deployed infantry and wiped out the detachment before pulling back.

"They [the Ukrainians] didn’t even bother to occupy the position," Platov added. "If they had known how bad the situation was, they would have taken all three of our lines."

The platoon’s next mission proved to be fatal to Platov’s comrades and nearly killed him as well. He blamed not the enemy, but the incompetence and brutality of his own command.

The platoon was dropped 25 kilometers ahead of friendly lines near Ocheretyne with no support and minimal supplies.

"We were told to bring our own food and water. I led the storm group, but we never reached enemy positions," he said.

Three stayed behind to maintain communications. The rest moved forward and were torn apart.

"The command told us, 'Advance, we’ve got our drone guiding you.' I said, ‘Which f***ing drone? There are three enemy drones to our right and two to the left. Are you nuts?' They answered, 'If you don’t move right f***ing now, our own kamikaze drone will hit your trench.' So we charged ahead. We didn’t even reach the contact line before Ukrainian drones destroyed us," he said.

Platov was hit in both legs, his back and his spine. There was no medical evacuation.

"I crawled for four days, 25 kilometers. Only two of us survived out of nine. We pissed in bottles, took antiviral meds and drank. That’s how we survived," he said.

Upon his return, Platov said he was treated like a traitor.

“They said, ‘You're the commander, right? Where’s your group? You’re a Wagner guy, weren’t you supposed to be tougher?’” he recalled. “But I wasn’t the one giving the orders — it was those idiots sitting in their cozy headquarters.”

Ordered to return to the front immediately, Platov refused what he saw as an “insane” demand. Only then did commanders approve a temporary pullback.

"In Wagner, it was brotherhood. No ranks, no insults. Everyone was 'brother.' You fought for the guy next to you. Here? You’re dirt," he said.

Serving in the Donetsk People’s Republic’s 110th brigade (formerly the 100th), he said Russian military police in the occupied Donetsk region would forcibly conscript men.

"They say Ukrainians kidnap men for mobilization. It’s the same s*** here. The military police stop buses, pull the men out, including students and seniors, and send them to the front," he said.

BBC reporting supports Platov’s claim that Wagner treated inmates more leniently. Life expectancy for ex-convicts in the mercenary company was higher than for those recruited by the Defense Ministry.

The “brotherhood” Platov described may stem from prison dynamics carried over into Wagner’s units.

Borovskikh suggested that Wagner’s recruitment practices allowed the informal prison hierarchy to carry over onto the battlefield, fostering a sense of loyalty and solidarity, although only among select groups.

"Wagner was Prigozhin’s project — less bureaucratic. They recruited anyone and formed separate units. The Defense Ministry has a list: crimes like extremism, terrorism or pedophilia disqualify you. Otherwise, they will take you," he said.

Platov now lives in a dormitory in occupied Ukraine, paying out of pocket after being denied hospitalization. Still, he hasn’t changed his mind about re-enlisting.

“Of course, I’m going back,” he said. “I’m not going home till I get payback for my leg. It’s not just revenge. I love my country. People say I went for the money. Sure, I got 2.5 million rubles ($30,441) for a contract. But I would’ve gone anyway. I just didn’t know I’d end up in this f***ng militia.”

Borovskikh said that while Russia sells the war as a patriotic cause, most prisoners join for money and freedom, with patriotism serving as a post-rationalization.

According to Russland hinter Gittern, about 25,000 convicts were pardoned and freed after serving with Wagner in Ukraine. Including Defense Ministry contracts, this total nears 50,000.

According to the independent news website 7x7, ex-combatants have committed at least 294 murders after returning home from the war. An earlier estimate by the independent news outlet Vyorstka said as many as 750 people may have fallen victim to violence at the hands of Ukraine war veterans.

Reports from exiled media and Russian and Ukrainian sources corroborate some of the details of Platov’s story:

- Reports surfaced in autumn 2022 of a man resembling Prigozhin visiting prisons in the Saratov region, where Platov had been serving his sentence for murder.

- The Mediazona news website reported that soldiers from the 110th Brigade locked servicemen and even a Chechen businessman in dog kennels as punishment.

- Another former prisoner who fought in the 110th Brigade after fighting for Wagner told Mediazona that he faced similar abuse.

- The 110th Brigade has been active on the Pokrovsk front, with fierce fighting around Zelene Pole confirmed by both Russian and Ukrainian military sources.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.