From St. Petersburg to Tbilisi, through art and exile, Leda Garina is a feminist artist and activist who has turned her flight from Russia into a radical form of resistance.

Founder of the feminist cultural project Eve’s Ribs, she has used body, language and irony to challenge authoritarianism, patriarchy and war.

In this interview, Garina, who fled to Georgia in 2022, discusses her commitment to opposing Russian militarism, her critique of imperialism, the necessity of provoking through art and the importance of communication as a political act.

“I don’t want to be a silent survivor,” she says. “I’d rather be a voice that insists on being heard, even if that comes at a risk.

Is war the main issue in Russia today?

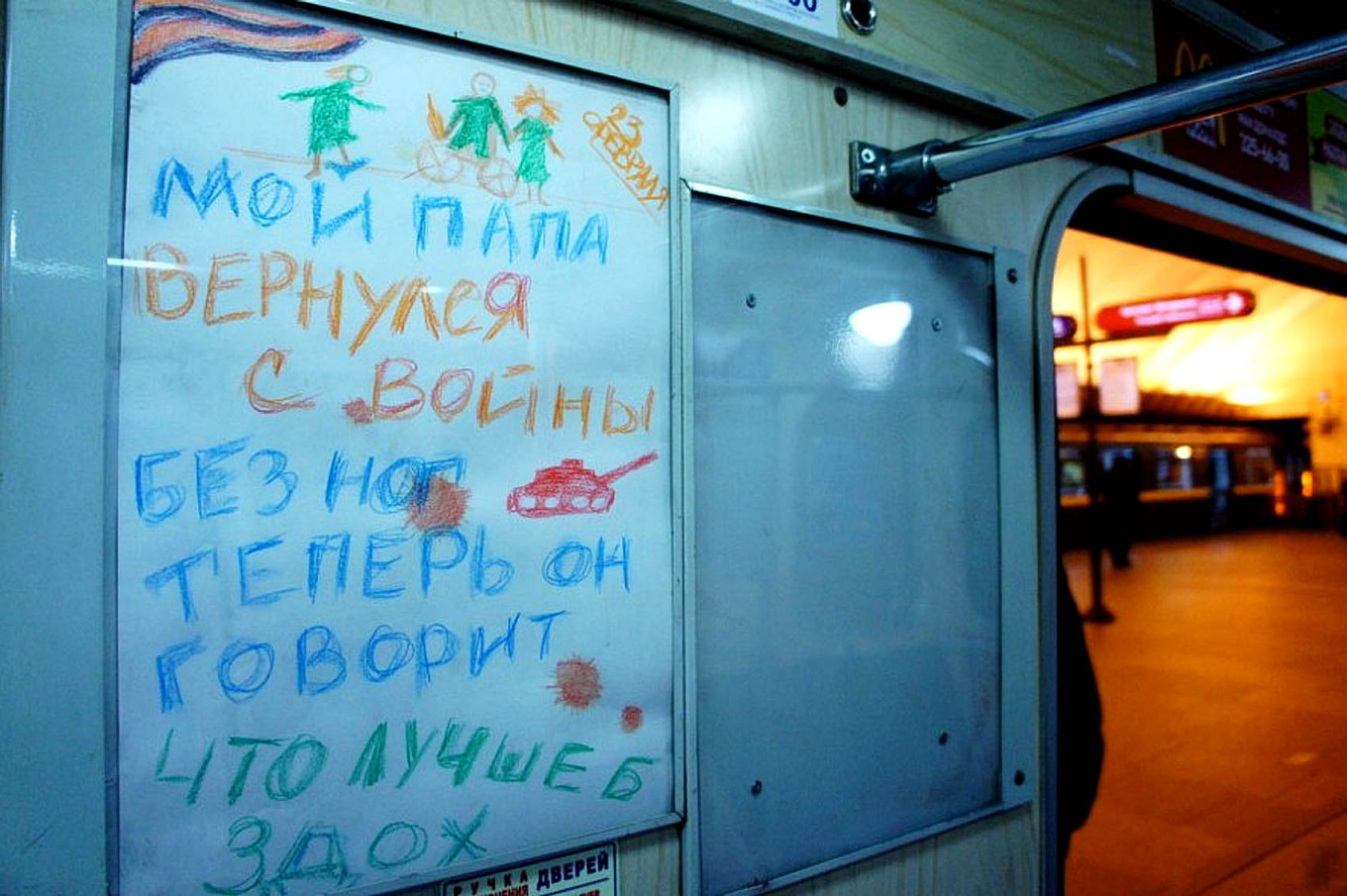

“Absolutely. For years, we fought on many fronts — environmental issues, women’s rights, freedom of expression — but today, everything is overshadowed by the war machine. If we truly want to stay connected to Russian society, we need to deconstruct its darkest core: militarism and imperialism. The narrative of ‘Great Russia,’ of military power, is a toxic fiction. It only serves to justify internal repression and external aggression.”

According to Leda, this ideological construction is not new — it is rooted in Russia’s colonial history. “Through our artistic performances and communication channels, we try to get people to reflect on how the idea of an empire legitimized to destroy, subjugate and erase the independence of other nations came to be. We are not a great country. We are a country that built itself by erasing others.”

Leda speaks with clarity, but also with visible pain: “Those who refuse to recognize Russian imperialism choose not to see it. But it’s there — in every war, every repressive law, every act of conquest disguised as national pride.” For her, cultural deconstruction is a necessary foundation for any political opposition. “We cannot fight for civil rights without dismantling the power structures that systematically deny them, at home and abroad. War is the symptom, not the disease.”

What role do feminism and art play in resistance?

“Fundamental. Feminist activism shaped me — it saved me.”

In St. Petersburg, Leda founded the region’s only independent feminist space, where she spent eight years organizing festivals, workshops, lectures and educational events.

“[Eve’s Ribs] was open to everyone, free of charge, built with care. But after the invasion of Ukraine, I realized we needed to expand our focus: it was no longer enough to fight only against cultural patriarchy. We also had to confront the armed patriarchy, which today is called war.”

Leda does not separate art from activism. On the contrary, she believes every artistic gesture is political. “The problem is that many activists today stop at expressing anger, without direction. We see symbolic actions, but there’s no real strategy. If we want to change something, we have to be ready to give something up.”

“It’s the same with other social struggles, like climate change. Everyone talks about saving the planet, but no one wants to give up their cars, flights or comforts. To truly change, we’d have to rethink our everyday habits, even the most intimate ones. But the system we live in has trained us to be lazy. We prefer to believe we’re in control rather than embrace uncertainty and make difficult choices.”

Leda observes that “political art” often stops at the surface. “Many actions seem provocative, but leave no trace. I want my art to truly disturb. When I receive insults or angry reactions, I know I’ve struck a nerve. If no one gets upset, then you haven’t said anything worth listening to. Art is an act of war against indifference.”

How can Russian citizens be moved to a broader reflection?

“That’s the question that haunts me most. Many people inside Russia claim to be against the war, but very few are truly willing to take risks. Most settle for a post or a hashtag on social media. There’s this idea that holding a moral position is enough to feel on the right side. But if you’re not willing to risk something — your job, your safety, your freedom — then you’re not truly resisting.”

Leda recounts an emblematic moment that she says happened after a TV interview: “An elderly woman came up to me and whispered, ‘You were rude — you interrupted a man.’ She didn’t care what I said, just that I broke the rules. That’s the tragedy: form matters more than truth.”

Even among radical groups, she has seen fear override action. “Once in Moscow, I proposed a concrete plan to free a detained activist. They told me we needed at least 100 people. Only four were willing to take the risk. Everyone else preferred posters and performances. It’s like we’ve convinced ourselves that looking good is enough to be good.”

To her, even many protests in Europe ring hollow. “A march in a European capital, holding a ‘No to War’ sign, isn’t dissent. It’s an exercise in moral hygiene. I respect it, but it’s not enough. It’s more about not feeling complicit than about changing anything. It doesn’t shake anyone.” And among younger people, she adds, “inertia is stronger than anger. Maybe because no one ever really taught us what disobedience means.”

And exile? Can you really speak of freedom outside Russia?

“There’s no truly safe place in the world,” she says. “In Georgia, I feel relatively freer, but I know it’s a conditional, precarious freedom. It’s an illusion. I carry the prison I came from inside me. And wherever I go, repression follows me.” She says there are rumors of Russian agents monitoring activists in exile. “I know I’m being watched. I know that if I returned to Russia, I’d be arrested immediately. Even staying here, every action carries risk.”

Still, she has not stopped. “To me, freedom is a daily practice, not a given condition. It’s something you defend every day, even when no one is watching.” She no longer expects protection from institutions. “Governments — even democratic ones — are slow, ambiguous. But communities can still make a difference. When you find a space where you can speak, create, help others — that’s your front line. That’s where you fight.”

She does not want, she says, to be a silent survivor. She prefers to keep speaking, even with a fragile voice — if it can help break the silence that protects power.

What actions lead to change, and how can they be carried out effectively?

“In a context of war and censorship, communication becomes an act of resistance,” she says. It’s a theme she returns to often: the idea that words, gestures and images must be intentional, precise, and meant to disturb. “Russian public communication is built on an illusion: the state tells you that you’re not responsible, that the enemy is outside, and that your suffering is justified. And many people choose to believe it — it’s easier.” But for Leda, dissent cannot be comforting. “You have to choose: do you want to communicate to look good, or to change something? I chose the latter. And that means losing support, frightening people, creating division.”

Based on these principles, Leda has not only organized political performances and protests but has also remained active online, using platforms like YouTube to rigorously dismantle imperialist narratives. “We don’t always know who’s listening, but we know why we’re doing it. Inside Russia, people need to know that someone is still speaking.” Even ironic actions, like dressing up as a squirrel to save a public park, can create attention and dialogue, she says. “Sometimes it’s through paradox that consensus begins to crack. It’s a slow process, but one I believe in.”

For her, effective communication is not about making people feel better — it is about moving them. “If even one person begins to question the propaganda they’ve internalized, that’s already a beginning.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.