In the past weeks and months, the attention of Russian, Ukrainian, and international human rights defenders has been focused on negotiations to end the war in Ukraine.

Back in January 2025, addressing the parties and participants in the negotiations, human rights defenders drew attention to the situation of prisoners of war from both sides, illegally detained Ukrainian citizens, Ukrainian children brought to Russia and Russian political prisoners. The resulting international campaign, ”People First,” called for making their fate one of the priorities in the negotiations.

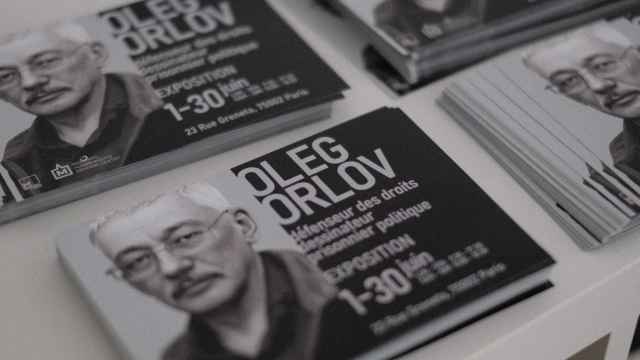

In February, on the third anniversary of the start of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, a group of UN special rapporteurs and experts repeated the call. They stressed that the Russian state must be held accountable for the aggression against Ukraine, including the war crimes committed during the aggression and for the repressive policy inside its country. After all, the invasion of Ukraine became possible thanks to the system of retaining power through political repression created in Russia over the decades. According to experts, the cases of more than three thousand prisoners in Russia are perceived as politically motivated on the part of the authorities. There are reports of them being tortured and held in life-threatening conditions, even to the extent that they died.

However, reports on the progress of the peace talks make it more and more doubtful that negotiations are based and focused on humanitarian issues, human rights and even the law.

Human rights as the foundation of the post-war world

In the 20th century, the concept of human rights, which formed the basis of international law and is enshrined in numerous international documents, became perhaps the main achievement of the humanitarian progress of humankind, which survived the horrors of two world wars.

After World War II, the countries participating in the coalition against the Nazis initiated the creation of the United Nations. The United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, from which a number of pacts and agreements have emerged. In 1975, the Helsinki Final Act was signed, which established the relationship between military-political security, and respect for human rights and democratic principles.

Respect for human rights was affirmed as a necessary condition for maintaining and strengthening international peace and security and developing cooperation between states. These documents and mechanisms were supposed to prevent World War III and guarantee the observance of the inalienable rights of every human being, regardless of race, gender, language, religion, political or other beliefs, national or social origin.

This system was not, and could not be, perfect. Wars broke out, crises erupted, and dictatorships continued to arise all over the world. The Western and Eastern blocs were in a state of Cold War while the world was on the verge of a hot war.

But still, World War III did not happen: nuclear catastrophe was prevented and humanity survived.

Important norms and values were established in world politics, anchored within the framework of the United Nations and the OSCE — values that could and should have been aspired to. Europe was assured decades of lasting peace. Humanity entered a period of economic growth, technological development and global cooperation — for a long time, it seemed.

After the collapse of the Eastern bloc — and then the U.S.S.R. — the formerly “socialist” and post-Soviet countries had the opportunity to independently build a democratic future. They opened their borders and internal markets, beginning to look for their place in the global community. The jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights was recognised by many of these new countries, including Russia.

An important participant in this movement towards progress was the United States of America, which became the source of advanced legal and human rights practices and institutions operating in many countries today. This movement itself was non-linear, and the United States has by no means always played a positive role. But in the end, its contribution to promoting democratic values and norms of international humanitarian and human rights law has been significant. Washington’s commitment appeared indisputable.

A return to a world without rules

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine became a decisive challenge to this all too fragile established system of international relations. For most countries, the Putin regime’s preferred principle of solving interstate problems based on the “right of the strong” through war, turned out to be unacceptable. Democratic countries provided Ukraine with assistance to repel aggression, although sometimes insufficient.

Since the end of January 2025, a new crisis has emerged, caused by the United States’ rejection of the legal standards and principles on which the post-war world was built. The new American administration’s policy is increasingly based on the same ideas about the “right of the strong,” on the fact that great powers can decide the fate of other states and dictate conditions to them. In its declarations and assessments, the United States relies less and less on international law, and assessments and positions based on this law are easily revised.

Too much about these changes reminds us of practices that have become well-known to Russian human rights defenders for the past 25 years. For us, the “world without rules” did not come to an end in 2025, February 2022, or even February 2014. For a quarter of a century, Putin has been rebuilding Russia based on the denial of human rights (which are subordinate to the “interests of the state”), the trivialization of the law and the claim that everyone is guided by their interests, not values.

Moving away from an order based on common rules to arbitrarily set terms and deals means denying the agency of both people and entire countries. We recognise all this renunciation of norms, down to the details, based on our experience of the last 25 years.

By wanting to find a solution to Europe’s main crisis and end the war in Ukraine — a quick solution, but more impressive than effective — the U.S. president is equating the aggressor with its victim through his statements and actions. One gets the feeling that throughout negotiations, he is more likely to protect the interests of the aggressor to the detriment of guarantees of the safety of people in Ukraine.

Dangerous consequences

Half a century ago, the great scientist, humanist and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov wrote: “Peace, progress, human rights — these three goals are insolubly linked to one another: it is impossible to achieve one of these goals if the other two are ignored.”

Today, world leaders talk about peace. But at the same time, the main principles of human rights and international law are catastrophically devalued. Such a rejection of the principles of law does not lead to peace and progress, but to an inevitable chain of new catastrophes.

Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine was the result of many years of trampling on human rights within Russia itself and the lack of a proper response from the international community to these violations. Now, the loss of legal and value orientations in international politics can cause disasters on a global scale.

An unjust peace — a so-called deal that contradicts legal norms — sets a dangerous precedent. It normalizes the Russian war against Ukraine, thereby giving the green light to a repeat of external aggression and a new wave of even harsher repression inside Russia.

Such a deal would be signal to the whole world a movement towards a dangerous, unstable situation, reminiscent of the eve of the two world wars of the 20th century. The departure from the principles of human rights and international humanitarian law in peace-making practice encourages impunity for crimes and will inevitably lead to new wars of aggression. Democracy in many countries will also be at risk, as the new rules of the game will open up wide opportunities for any autocrats and dictators. They will be able to suppress dissent and violate human rights in their countries without regard for their obligations to international institutions.

There will be no peace without the law

We call on the leaders of all democratic states, all politicians for whom human rights are not empty words, and civil society in all countries to make resolute efforts to bring law back into international politics.

This is the only way to create reliable conditions for long-term peace in Europe and prevent the emergence of new large-scale military conflicts across the globe. Otherwise, the whole world will soon find itself in a situation where the fate of people and countries will be decided solely by imperialist predators through wars and bargaining.

We call on all participants in negotiations to achieve peace in Ukraine to put the human dimension first: namely, the fate of prisoners of war and the protection of civilians, including in the occupied territories.

We insist that negotiations should be based on the fundamental norms of international legal agreements, the UN Charter and the Helsinki Final Act, since they define the concept of aggression, uphold the principle of territorial integrity and sovereignty and link military and political security with human rights. Without this, it is impossible to achieve a just and sustainable peace.

This is an adapted version of an open letter published on May 25.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.