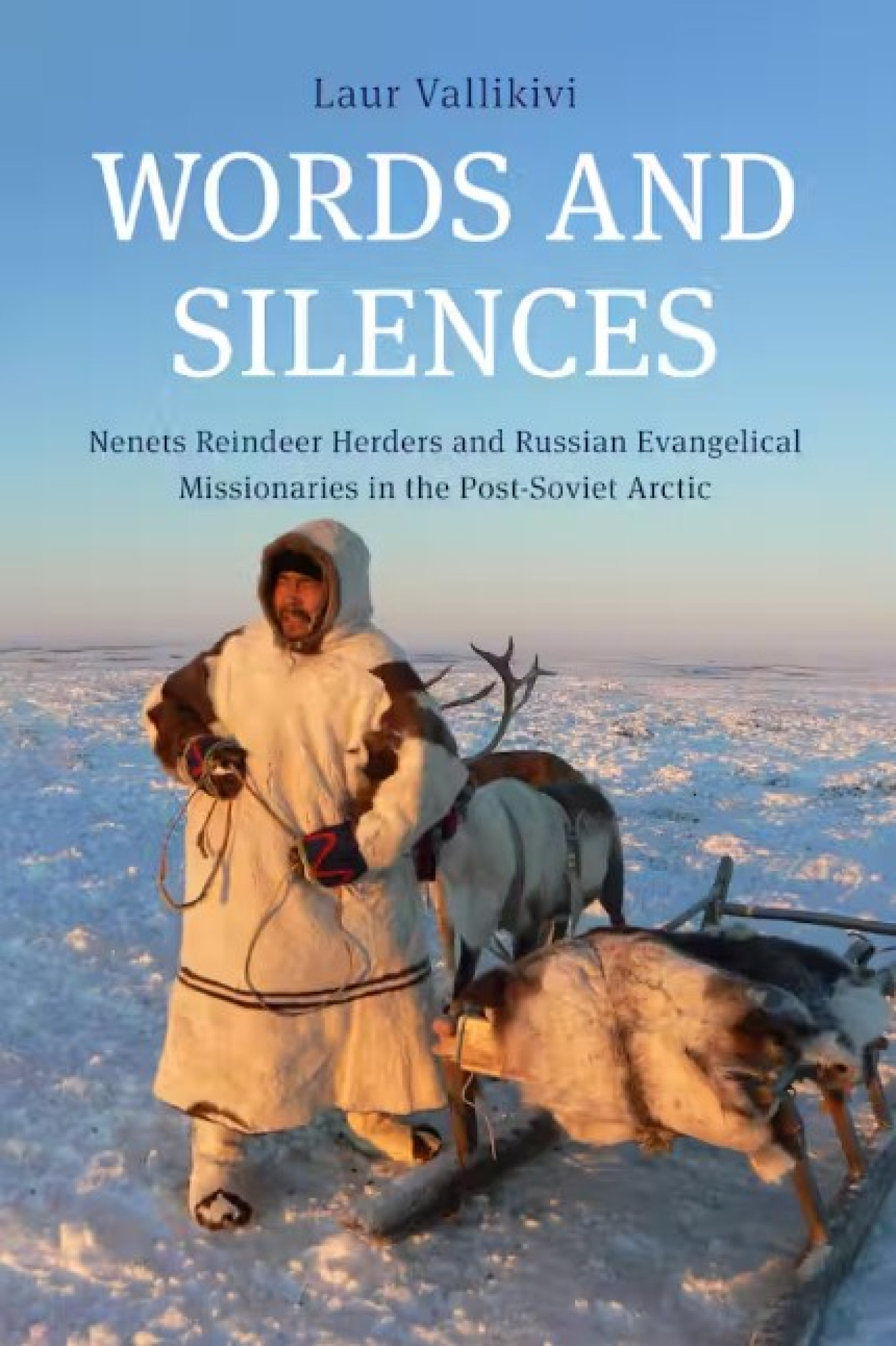

“Words and Silences – Nenets Reindeer Herders and Evangelical Missionaries in the Post-Soviet Arctic” is the first book by Estonian ethnologist Laur Vallikivi, and draws on twenty years of fieldwork amongst indigenous communities in the Russian Far East.

Vallikivi acknowledges that the Soviets and their predecessors committed many atrocities against such communities – conscripting them, collectivising them, taking their children away to boarding schools, raiding their land, and hunting its animals towards extinction. The story of colonialism has played out many times across every continent – yet Vallikivi finds a narrative that has escaped much of the world’s attention. Early on, he describes “Words and Silences” as “a story of a striking failure” – due to their nomadic lifestyle and the vastness of the land, two small communities of reindeer herders, the Ural and Yamb-To Nenets, managed to hide and survive the Soviet period more or less unscathed.

A fascinating premise – and there’s another twist. Vallikivi introduces a second unexpected group: Baptist and Pentecostal preachers. These evangelical Christians also went into hiding during the Soviet period, as their “unregistered congregations” were viewed as a threat to the accepted truth of the regime. In rivalry with each other as well as the state, the banned Christian sects roamed the Arctic “competing for souls.” Here they crossed paths with the reindeer herders – and despite their own experiences of forced conversion, sought to draw them “to the light.”

Thus, many reindeer herders preserved their shamanistic belief system against all odds, only to become Christians in the 1990s. The descriptions of white Russian speakers disturbing traditional settlers and encouraging them to burn their icons and abandon their gods are certainly jarring to read about.

Yet Vallikivi argues that there is more to religious conversion than meets the eye. He finds examples of Nenets who went willingly to the Baptists – due to tensions in their family groups, struggles with alcoholism, or simply the desire to learn to read. The author lived with some of the Christianised Nenets for periods of several months at a time, making multiple visits to the same families after his initial visit to the region in 1999.

Other Nenets – mainly older men and women – resisted the proselytising of the Baptists and responded to the new influx of songs and prayers with stubborn silence. Vallikivi has time for this story too.

At its heart, “Words and Silences” is an academic and philosophical text about what it means to believe “in” something; why a person chooses to cross from one “in” to another – and whether one is free to make this choice in the first place. It is one of the most original volumes to arrive in a year filled with important new scholarship.

Words and Silences – Nenets Reindeer Herders and Evangelical Missionaries in the Post-Soviet Arctic

From Part II

Conversion of People, Disenfranchisement of Spirits

Prologue: A Service in a Nenets Mya

On a cold Sunday toward the end of 2006, in the dull half-light of a late morning during the months of polar night, a few families arrived on their reindeer sledges to attend a service in the camp of Andrei, the Nenets presbyter of the Baptist church. Among those who arrived from nearby camps— at a distance of a few dozen kilometers—was Andrei’s brother Yegor, with whom I had recently completed the autumn migration. By December, all the Yamb-To Nenets had made their way from the coast of the Kara Sea to the winter pastures after two months of isolated travel southward, being once again capable of trips to one another’s myaq and to the city to sell and buy. This was also the time when the missionaries paid occasional visits to the camps. Most of the church life still took place in the tundra, as people found their way to the city prayer house not more than a couple of times a year. Missionaries did not like this infrequency. I heard Pavel, the presbyter of the Baptist church in the city, reproaching herders now and again, saying that “the brethren from the tundra” came to Vorkuta without attending services in his prayer house. As usual, the Nenets were silent when admonished. However, since Andrei had been ordained a presbyter, some said that they no longer needed to visit the city church that often. Although they did not cast doubt on the need for utmost commitment to the teachings introduced by Pavel and other missionaries, this was one of the signs that the Nenets converts were trying to carve out their own cultural space and style of being punryodaq, “believers.”

In most ways, in the morning before the Sunday service, except for a prayer before and after eating, nothing would betray that these herders were different from non-Christian herders. Neither their outfits nor the way they spoke marked the distinctiveness of the day of repose or the Christianity of their “inner lives.” Indeed, until recently, Sunday (khekhe yalya, “sacred day”) visits were accompanied by vodka, tobacco, and cards, these now being taboo. In addition, Nenets songs, wrestling, reindeer races, and drinking of raw blood after butchering a reindeer for guests were no longer part of social life. While some of these activities, such as wrestling, were claimed to be just vanity and a potential source of unhealthy rivalry, drinking blood was said to conflict with God’s Word, which banned it outright. Singing personal or epic songs had been outlawed because of the perceived danger that this would pull a person back into the old way of being, and so was somewhere between vanity and “paganism” (yazychestvo).

After eating, some casual chat, and occasional laughter, Andrei declared that it was time to start with the service. Sitting on reindeer hides, congregants became somewhat more serious, and everybody’s gaze turned to the pastor who was about to lead the service from where he was, sitting near the pure part of the mya under the kerosene lamp (si, i.e., the part where foodstuff is stored, and, before conversion, sacred items). Rather than the spatial structure of the confrontational pulpit and pews—segregated by gender—in the prayer house, people stayed where they usually were (by a loose principle, the most honorable male guests are closer to the si). Andrei gave an introductory prayer, with a deep and measured voice, in which he called for the Holy Spirit to come among them. Then, he took out his Russian Bible from the leather case and read slowly but firmly a preselected passage from Matthew, translating it sentence by sentence into Nenets and further explaining the message with his own words in the vernacular. After finishing the passage, he continued with a short sermon using examples from everyday life and thus shifting listeners’ imagination between the doings of Jesus and of the “we” here and now. The written word unfolded into a spoken word of instruction, transferring some of the authority hidden in the text to the one who voiced it. People were listening, fiddling, and looking at one another. From time to time, the hostess of the mya, Lyuba, added long willow branches to the metal stove. The fire was crackling, and a stew was boiling.

Just as the spatiotemporal configurations were not fixed, so the language of Andrei oscillated between the two idioms. Although he mainly spoke Nenets, some Russian words had found their way into Nenets, like “be alert” (bodrstvuyte). Some Nenets words were also struggling to free themselves from their history—for instance, the word for “Satan,” ngylyeka, “an underworld spirit” that carried a whole gamut of experiences from the “pagan” past, especially for the older generation who had engaged with local and ancestral spirits during their lifetime. As always, Andrei harangued— although considerably more mildly than the Russian missionaries—the congregants about the need to try harder to study the Bible, follow what it prescribed, and pray to God more often. As he said, without these actions, there was no hope of God’s protection here on earth or thereafter. His language was based on “a grammar of desire and fear,” reminding listeners how their fates were tightly related to rewards and punishment.

In his sermon, Andrei also quoted Bible passages by heart, a skill that only a few Nenets commanded. His greater ability subtly hinted at his greater holiness and authority at that moment in an otherwise egalitarian community of brethren and sisters. As Yegor’s wife, Lida, told me after, “We all pray for him, and so God must have given him more than others.” Lida referred to a fundamental point that has its source in Christian understanding that ordained presbyters like Andrei acted as a composite agent entailing both human and divine components. Whereas “ordinary” believers were also composites, the overall sense was that the Holy Spirit was acting more powerfully in Andrei, Pavel, and other pastors whose greater skills were a sign of God’s greater investment in them.

Closing the Bible, Andrei called for prayers in Russian: “Let us pray” (davayte pomolimsya). This had become an evocative phrase that the missionaries repeated again and again. After a short silence, Andrei’s sister’s husband, Yevgeni, was the first to start. Fluent in Nenets, Komi, and Russian, as are many youngsters, he began the first sentence of his prayer in Russian but finished it in Nenets: “Great God, glory and gratitude is yours!” (Velikiy Bog, slava i blagodarnost’ pydar nyand!). Others kneeling nearby were attentively listening; a few were moving their lips in silence accompanying Yevgeni’s prayer, which was interspersed with his sighs suggesting that the words were coming from the heart and were deeply felt. Then Yevgeni’s wife, Ksenya, performed her prayer, which was barely audible, like the ones from other female converts. The prayers contained, as usual, a thanksgiving for how things are, no matter whether good or bad, followed by an admission of one’s sinfulness, a request for forgiveness and purification, petitions of a general or particular order (the well-being of one’s family and reindeer, a safe journey, etc.), all these elements bracketed with phrases praising God and with repeating of “Not my will but thine be done.” The short prayer session, in which nearly all present made their petitions in Nenets, was finalized by Andrei, who prayed louder and more fluently than the others who were unable to speak with similar authority.

Without leaving too long a pause, Andrei said the number “seventyfour,” which marked a song called “Oh, I Am a Poor Sinner! Truly I Am One” (O! Ya Greshnik Bednyy! Pravda, Ya Takov) from the Baptist hymnal in Russian (Pesn’ 2004). This melancholy hymn speaking of Christ’s gift to sinful humans had become one of the favorites among the church members (alongside a hymn on Vorkuta). All who were able to read, even if not that well, opened the hymnal. Others who were illiterate sang along with the parts they had memorized. Now and again, the tune slowed, as if on an old record player. Following the principle of the priesthood of all believers— or more precisely, “the priesthood of all male believers,” as women were not allowed to sermonize—in the next round, Yevgeni did the reading. The cycle of reading and singing intermingled with prayers was repeated twice more.

As in the city church, individual believers were encouraged to sing or read a poem they knew by heart in front of the congregation. Yegor, who struggled with reading and whose ability to sing Russian songs (yanggerts’) was modest (in contrast with his masterful performances of epic songs), moved with his literate daughter Alla to the door area, which offered a square meter for a stage. Alla started singing, her father following her with evident lack of self-confidence, yet performing until the end.

As Andrei commented afterward, God must have been very pleased to see Yegor taking the stage despite his inability to stay in tune. His comment characterizes the overall expectation and pressure among the Baptists: one must do more than one thinks is possible as the Holy Spirit helps out. The service ended with men and women shaking hands and with brotherly or sisterly kisses on the lips among people of the same gender. The Baptists stressed that kissing reinforces brotherhood and peace, taking a lead from Romans 16:16 (“Salute one another with an holy kiss. The churches of Christ salute you”). After the service, Lyuba served tea, meat, and fish. Then, in the complete darkness of afternoon polar night, the guests left toward their camps.

Excerpted from “Words and Silences. Nenets Reindeer Herders and Russian Evangelical Missionaries in the Post-Soviet Arctic,” written by Laur Vallikivi and published by Indiana University Press. © 2024 Laur Vallikivi. For ease of reading, references have been removed. Used by permission. All rights reserved. For more information about the author and book, see the publisher’s site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.