In the dead of a cold January night in Ulyanovsk, a Molotov cocktail smashed through a ground floor window of a wooden house. Within seconds, the room was ablaze: curtains, blankets, and a bed containing a two-year-old baby. The child would survive — miraculously — thanks to doctors and quick actions by his grandfather, Ismail Guseinov, but was badly burned.

The bomb had been thrown by a debt collector seeking repayment of a loan. A few months earlier, Guseinov had needed cash for medicine to help a bad back. To get it quickly, he turned to a pay-day lender, and agreed to a high interest loan of 4,000 rubles ($50).

By January, however, he had fallen behind on payments and a local collection agency became involved. They demanded immediate repayment of a sum ten times larger than the original loan — 40,000 rubles.

The collectors did not immediately reach for their Molotov cocktails. The first warning, a few weeks prior, was a brick thrown through the window. The message on the brick left no doubt as to their further intentions: "We'll burn your house down," it said. The collectors began calling Guseinov's children.

Guseinov was alarmed and reported the matter to the police several times, but they failed to react adequately.

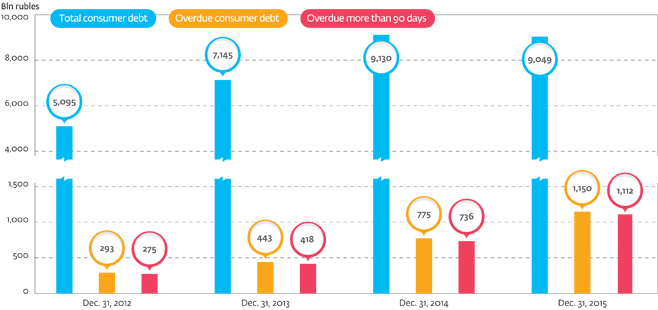

The violence was shocking, and left the Russian public looking for answers. But the family's predicament was unexceptional. Incomes have been falling during Russia's economic slump, and more people than ever are struggling to repay loans. During 2015 the value of overdue loans increased by almost 50 percent to 1.15 trillion rubles ($15 billion).

According to Alexander Akhlomov, an executive at the United Credit Bureau, which monitors credit history, 11.5 million Russians held overdue debts by the end of December. Seven million people were more than 90 days in arrears. And an under-regulated, sometimes predatory collection industry is capitalizing on their predicament.

Debt Bubble

At the start of the decade, consumption was wild. "Time to have it all," said the credit companies in advertising campaigns. "Take it, you can return it later," the slogans crooned. And, as borrowing peaked and the economy stalled, a parallel collection industry grew up for those who couldn't pay.

Some banks began in-house debt recovery, but many began selling overdue loans to specialized agencies. These firms often operate on the edge of the law. "In most cases the activity of collectors is directly connected to criminality," the Prosecutor General's office said in a statement earlier this year. These agencies process more than 40 percent of bad debts, says Akhlomov — meaning that at least 3 million Russians are targeted.

Professional bodies representing debt collectors are keen to point out that many of these people are fraudsters who took the money without intending to repay. They also say their members don't use Molotov cocktails. Banks and respectable collectors stopped using rough methods "long ago," said the president of the Association of Corporate Collectors, Dmitry Zhdanukhin. But even if open violence is relatively uncommon, intimidation appears to be widespread.

Danila Mikhalishchev might be described as a veteran of the industry, having worked in debt collection during the early 2010s, first at a major Russian bank and then at a collectors agency called Sequoia Credit Consolidation. He described the three stages of collection: "Light" collection, which means polite phone calls reminding people to pay, lasts for a couple months. Then it switches to "medium," when calls become more insistent. At three months, "hard" collection begins, and collectors start visiting.

Even large, respectable lenders use intimidation tactics. Mikhalishchev said the bank had trained him to use psychological pressure: "People pay up because they don't know their rights and because they are afraid." Threats work in a country where memories of lawlessness and gang violence in the chaotic 1990s are still fresh, former collectors said.

Officially, bank employees weren't allowed to threaten people. Instead, they would harangue borrowers with a call every two minutes and say: "If you don't pay, your credit history will be ruined."

But employees found that the more menacing they were, the better their results, says Mikhalishchev. The bank had a bonus-driven culture, and "supervisors turned a blind eye" to rule-bending. Call center staff came up with various ways to turn up the heat: "They bought SIM cards on the black market registered to other people and rang from them, because landlines were recorded and monitored."

From untraced lines, they could plug into the darkest side of the business — mobile collector squads. Their methods include setting fire to doors, injecting glue into locks, scrawling insults on entrances to apartment blocks, threatening family and friends, trashing property and scratching cars. According to former collectors, they rarely supply documents to back their claims.

The Moscow Times obtained a recording of a call from a collection agency. It was taped by a borrower in the Siberian city of Novokuznetsk who collected evidence against the people threatening him.

In the recording, two people from a collectors call center play bad cop and even-badder cop. A woman, who does not introduce herself, ridicules the borrower for the small, "unmanly" size of his 10,000-ruble ($130) debt and asks if his parents have had heart trouble. "You believe you won't be punished. Collectors will beat that out of you," she says, adding: "Get your hankies ready."

Suddenly, she passes the line to a male colleague. "You didn't forget me did you?" he asks, and threatens to hand his debt over to thugs. "Tomorrow or the next day you'll be seeing people like Solnyshko Vladimir," he says, referring to a local gang leader. "I think that'll be jolly … We're washing our hands of any responsibility."

The debtor objects: "You said you were an organization that works with borrowers before cases go to trial. If so, let's go straight to court."

"'Before trial' means 'without a trial,'" he is told.

Bad loans rising: Annual consumer debt in Russia from December 2012

Police

Making things worse is a distrust of the police. "Of course there is no point hoping in law enforcement," said Mikhalishchev. There's rarely any reaction, he adds — they're just as likely to ask: "They didn't kill you, what are you bothering us for?"

Collectors usually commit petty crimes that are difficult to prove, and high staff turnover makes it even harder to find suspects, said Mikhalishchev: "Collection agencies and banks work with hundreds of people. Staff changes every three months, so try finding someone."

The man who threw the Molotov cocktail in Ulyanovsk was a 44-year-old former policeman named Dmitry Yermilov. According to media reports, he had a rich history of threatening residents and vandalizing properties. Following that incident, the heads of the country's two most powerful law enforcement bodies, the Prosecutor General's office and the Investigative Committee, announced they would personally look into the collecting business.

Predatory Lenders

Meanwhile, the problem grows. Russians' incomes declined last year for the first time since the 1990s, and an economic slowdown is likely to continue through 2016. The value of overdue loans "could certainly reach 1.5 trillion rubles this year," said the United Credit Bureau's Akhlomov. That would be a rise of one-third from the end of December.

As more people fall into arrears and spoil their credit history, more will be turned away by banks. This could force them to turn to more predatory lenders — so-called micro-lenders who deal in pay-day loans at interest rates that reach several percent per day.

These are already popular. Twenty-five years after communism, many people in remote regions remain wary of banks. Credit card infrastructure is patchy, and major lenders don't deal in the small loans needed by poorer people. In larger cities, many migrants don't have access to legal banking services.

"The micro-finance industry is developing rapidly and replacing some of the banking industry in some localities," says Alexander Morozov, deputy head of the National Association of Professional Collection Agencies. They are aggressively marketing themselves and their collectors are the ones who hit the headlines, he said.

Officially, these micro-lenders have handed out loans worth about 150 billion rubles ($1.9 billion), and two-thirds of borrowers are overdue, according to Akhlomov. But many operate outside the system. These lenders aren't interested in things like regulation and a client's credit history, said Mikhalishchev. "They want your passport data. Then they find you. Then they apply interest rates that turn the 10,000 rubles you took into 110,000."

"They make money on fear. They throttle you. That's all."

Retaliation

On the back of the Ulyanovsk scandal, legislators have demanded new regulation that could restrict or outlaw collection agencies. Officials are keen to be seen doing something ahead of parliamentary elections in the fall. A law to control debt collection is likely to be drafted in the near future. Morozov says this will help "the professional guys" by removing "grey parts of the market."

But the danger is that the new measures will have the opposite effect. Collectors will either redouble their savagery to collect as much cash as possible while there is still time or move further underground to escape new rules, former collectors said.

In the absence of effective policing, victims are organizing their own defense. Lawyers and former collectors have formed advice groups and consultancies. They usually tell people to either simply ignore demands for debt repayment or seek a court settlement. If you pay a collector, "You'll just bring down an even greater cabal [of collectors] on your head," said Mikhalishchev, who now works with OFIR, an anti-collection agency that offers legal advice.

Alexander Naryshkin is the administrator of Stop Collector, an online forum for victims of collectors that offers support and advice and receives 90-120 pleas for help every day. He plans to meet force with force.

"This year we're going to launch mobile anti-collector squads," he said. For a small fee, muscular men will arrive on the scene and make their presence known to collectors. "If they don't get it the first time, the second time we apply physical force. After the second time, I think they'll understand."

Vigilante justice is not new for Russia, having been a feature of the dog-eat-dog 1990s. Collectors like Yermilov in Ulyanovsk are still living in those times, says Yevgeny Romanov, a former collector: "They are men who never made it but still think they are the heroes of some Tarantino film."

Another version is that they, like everyone else, are trying to feed themselves and their families during the downturn. Only they have no scruples, says Naryshkin: "These people couldn't give a damn about anyone else."

Contact the author at p.hobson@imedia.ru. Follow the author on Twitter: @peterhobson15

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.