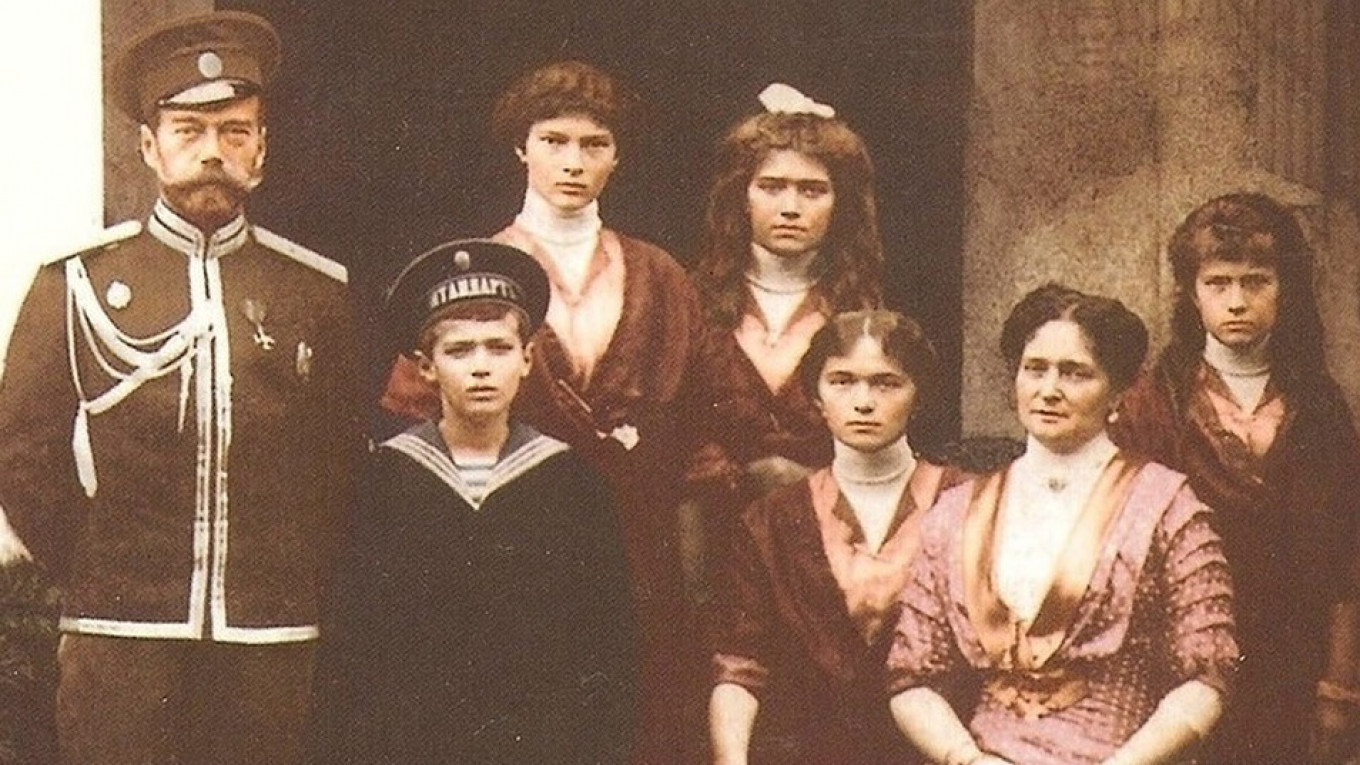

July 17, 2018 marks 100 years since Russia’s Romanov family was executed by Bolsheviks in the basement of the Ipatiyev house in Yekaterinburg. Tsar Nicholas II had abdicated a year earlier, and after a period of confinement, the family was sent first to Tobolsk and later to Yekaterinburg. The deaths of Nicholas and his heir Alexei were pivotal to consolidating the Revolution, excluding the possibility of a return to monarchy.

It was only in the 1990s, after the fall of the Soviet Union, that the remains of the Romanov family were excavated, identified and confirmed by state authorities. On July 17, 1998, on the 80th anniversary of their deaths, Nicholas and his family were given a state funeral in St. Petersburg attended by statesmen, diplomats, representatives of the Romanov family and European nobility.

In his address at the funeral, then-President Boris Yeltsin called the murders “one of the most shameful pages in our history.” Recognizing that “many years we kept silent about this monstrous crime,” Yeltsin underscored the historical chance to atone for a “century of blood and lawlessness” for the sake of current and future generations.

Yet the 100th anniversary of Romanovs’ deaths is passing with little notice from the government. Outside Yekaterinburg, there are few events to mark the centennial. Prominent venues expected to host such events, like the Historical Museum and the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, currently hold no exhibitions to mark the anniversary. In the capital, events are limited to a one-off requiem concert at the Tchaikovsky Hall and a multimedia presentation “Nicholas II,” screened once every few days in a small Sokolniki Park pavilion. In St. Petersburg, the Rosfoto Center is holding a photo exhibition. In these few events, the discourse of the Romanovs’ deaths is almost dissolved in the stories of their lives, their glamour and “greatness.” Otherwise, the dearth of events and their relatively modest locations speak volumes of the current state of historical memory.

The death of Nicholas II and the Romanov family remains a controversial moment in Russia’s history. Tsarism and Bolshevism are — for the most part — not presented as conflicting forces in a battle in which one order defeated another. Rather, tsars, Bolsheviks and later communists, are seen as a succession of “greats.” In Moscow, visitors can admire the glamour and grandeur of the tsars at the Historical Museum in the Red Square before lining up for the Lenin Mausoleum only a few steps away.

Today, Russia is facing a rise in the popularity of pre-Revolutionary culture alongside an enduring Soviet legacy. According to recent polls by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM), the popularity of Nicholas II, as well as Lenin and Stalin, has increased considerably since 2008. President Vladimir Putin, who embraces one-man “greats’” from all Russian eras, embodies this unusual combination.

The narratives of conflict and violence have been subsumed by narratives of “great” leaders. This cult of greatness celebrates impact over ethos. It nurtures a vacuous understanding of Russia’s political traditions and legacies at a time when Russia’s fledgling civic values require a recognition of the past. By denouncing Bolshevik tactics in his funeral address of 1998, Yeltsin tried to set some of these new values. He ended his speech with the lesson learned from Russia’s 20th century: “Any attempts to change life with violence are condemned to fail,” he said, as “[one] cannot justify senseless cruelty by political goals.”

The national narrative of “greats” also stands at odds with academic interpretations, which take a critical perspective of both Nicholas II’s often inept governance and of the Bolsheviks’ violent excesses. But the canonization of Nicholas II and his family by the Russian Orthodox Church as Christian martyrs in 2000 diminished their identity as political actors subject to academic scrutiny. In Yekaterinburg, where the largest events marking the centennial of the Romanovs’ deaths are being held, the Romanovs are martyred saints revered by devoted pilgrims, with virtually no reference to politics, policies or ideology.

The memory of Nicholas II’s and his family’s deaths remain largely unprocessed, and the paltry number of commemorative events on the centennial hardly suggests a step forward. But one project does, perhaps, respond to Yeltsin’s assertion at the funeral that “we are all responsible for the historical memory of our people.” The State Archive of the Russian Federation has launched a remarkable digital project called “The Murders of the Royal Family,” a trove of digitized photographs and documents related to the deaths of Romanovs.

Russia’s political traditions and civic values for the 21st century will not rise from a cult of greatness; they can only be built on remembrance and reconciliation with the past, however difficult, bloody and lawless it may be.

Ala Creciun Graff is a doctoral candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park. The views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.