ISTANBUL – As the last rays of the setting sun shone through Istanbul Airport’s floor-to-ceiling windows on Wednesday, a large group of Iraqi men, women and children gathered in front of the departure gate for Minsk.

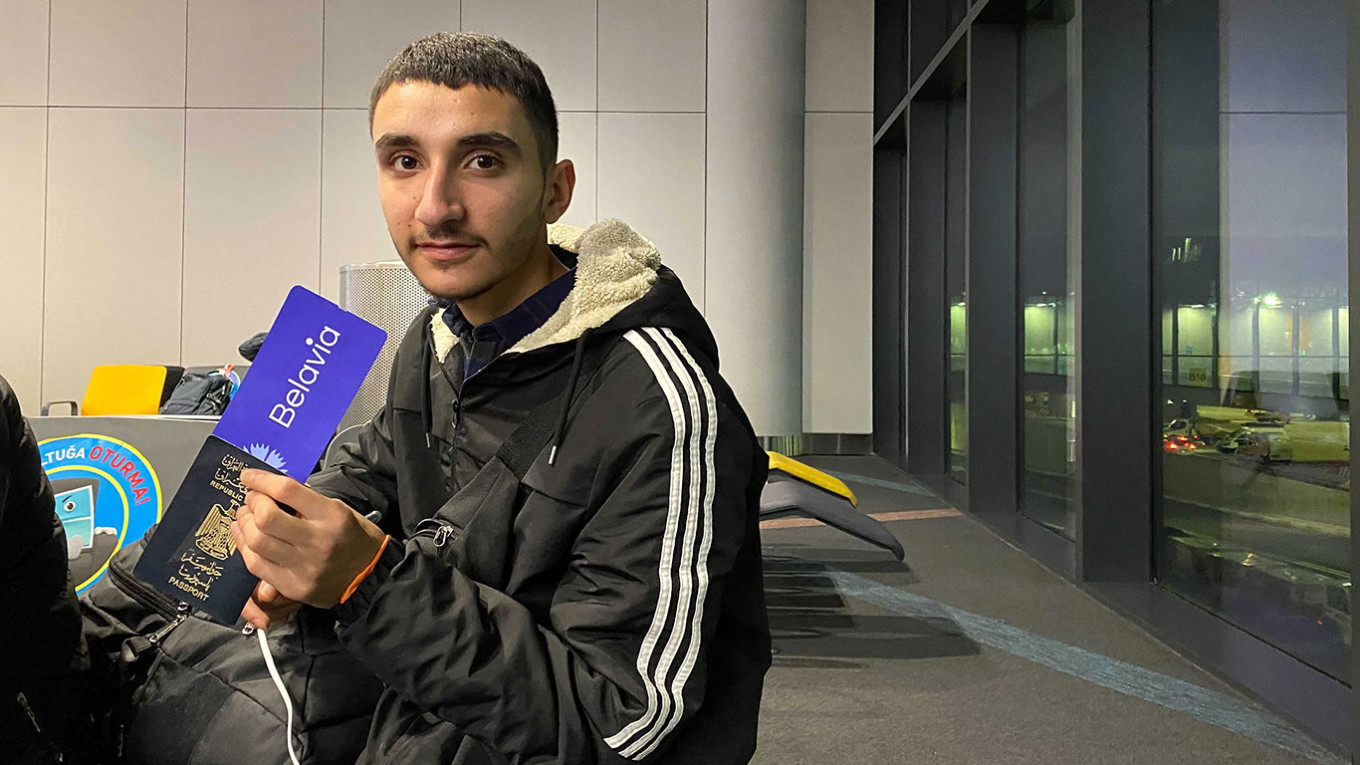

“This is our lucky ticket, we are going to Europe,” said Zoran, 18, wrapped in a thick winter coat and weighed down by three big bags as he waited to board the flight to the Belarusian capital operated by the Belavia, the national carrier. Two days later, Belavia announced it would no longer allow Iraqi, Syrian or Yemeni citizens to fly from Turkey to Belarus.

Zoran had already traveled from his hometown of Zakho, a Kurdish city in northern Iraq, first by bus and then by plane from Erbil, the capital of Iraq’s Kurdistan region.

Like thousands of other Middle Eastern migrants who have made the treacherous journey to the Belarusian-Polish border in recent weeks, he is determined to reach the EU and ready to face the freezing conditions in makeshift forest camps near the razor-wire fence that separates the countries.

“I have no choice, life is dangerous and hopeless in Iraq. I am ready for the crossing,” he said.

The EU accuses Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko of deliberately orchestrating the growing border crisis, luring migrants to his country to cross into EU member states Poland and Lithuania in retaliation for Western sanctions imposed after his disputed 2020 election victory.

The bloc has now turned its attention to the air carriers that have been transporting the migrants to Minsk from airports in Istanbul, Beirut, Damascus and Dubai. Iraq suspended all passenger flights to Belarus in August after coming under EU pressure.

Three flights a day depart for Minsk from Istanbul, operated by both Belavia and Turkish Airlines. Belarusians themselves are mostly banned from leaving the country due to Covid-19 regulations.

Poland on Tuesday slammed Turkey for maintaining an open corridor between Istanbul and Minsk and helping Belarus to bring thousands of refugees to its border, accusing Turkey of synchronizing its actions with Belarus and Russia.

Reuters reported this week that the EU is currently close to imposing more sanctions on Belarus over the migrant crisis, including banning Belavia from being able to lease aircraft from Danish, Romanian and Irish firms.

And on Wednesday, Bloomberg said the EU and the U.S. were also considering introducing sanctions on Russia's state carrier Aeroflot and Turkish Airlines, blaming them for flying migrants into Belarus at Lukashenko's behest. Aeroflot on Thursday denied the allegations while Turkish Airlines later announced it would no longer allow Iraqi, Syrian and Yemeni nationals on its flights to Minsk.

Belavia ground staff separated Iraqi citizens from other passengers as take-off time approached in Istanbul.

“If you are from Iraq, please proceed for boarding in a separate line,” shouted a woman in the blue Belavia uniform, as a group that far outnumbered the other passengers began to form.

Many of the migrants in the queue had only a vague plan of how they would make it to the Polish border, let alone to Europe.

“We will go tomorrow or the day after, maybe even tonight,” said Afron, 16, adding that he was traveling alone with his parents’ blessing.

He pointed to his feet when asked how he was planning to get to the border.

“My friend, I am strong,” he said.

Once the plane was full, Nzar — a 24-year-old maths teacher from Iraqi Kurdistan sitting next to me in row 24 — took out his phone and sent selfies showing his successful boarding to friends and family. An atmosphere of relief pervaded the plane as the wheels started turning and it detached from the gate.

“We made it, we are taking off,” Nzar said.

Nzar said he was trying to get to Germany to reconnect with his girlfriend and two brothers who gained asylum in Berlin during the 2015 European migrant crisis.

At that time, he walked from Turkey to Germany, but was denied asylum and deported back to Iraq. He now hopes the flight to Belarus will give him a new chance to see his loved ones.

“I have given up everything I have to see them again. I am going and not turning back. I’ll camp all winter if I have to,” he said.

For many, the journey to Belarus cost a life’s savings.

Nzar said he paid “a middleman” in Iraq $2,000 for a one-week Belarusian tourist visa, which he proudly displayed. The fixer also charged him a further $600 for a hotel room.

Others have made use of the many Belarusian travel agencies, some with reported ties to Belarusian authorities, that have recently sprung up in cities across the Middle East.

“It was extremely easy to get the visa, less than a week. If you have some money,” Nzar said.

A female Belavia crew member at the rear of the cabin said she first noticed more citizens from Syria and Iraq boarding flights to Minsk in the summer.

She joked that it has since become an “open secret” that the airline is transporting “tourists” planning to cross the border to Europe.

“We have been flying refugees for months now…Everyone knows what we are doing. We all watch the news,” she said.

The crew member complained that the flights have led to an influx of migrants in her home city of Minsk, referring to social media images showing migrants sleeping rough in underpasses.

“But this is politics. There isn’t much we can do about It,” she added.

Social media

Back in row 24, Nzar’s friend Rebin, who had a well-groomed beard and wore an NBA hoodie, was staring at his phone, scrolling through a Google Maps card of Belarus.

“Do you have Snapchat?” he asked, as he took a picture of the soggy ham sandwich served after takeoff.

“These pictures are for my friends back home, many want to come too,” he said.

Social media and apps like Snapchat and Instagram have made it easier for migrants to communicate with each other and provide tips on how best to travel and get to the border with Poland. Many on the plane were carrying two power banks with them.

But social media has also led to more awareness among the migrants of the struggles they will face when they reach Belarus.

“It’s going to be shit, I know, I know. I have seen the videos,” said Rebin when asked about the prospect of walking miles to the border and sleeping in a tent.

He said he was aware of the latest reports of some migrants freezing to death.

Polish border police have reportedly used tear gas to deter migrants from crossing over, while on the other side migrants have reported being beaten by Belarusian guards. Poland has recently massed over 12,000 troops and the Polish Defense Minister has said his country is "prepared to defend the Polish border."

The UN refugee agency has said that at least eight migrants have died of cold at the border. Human rights groups believe the toll to be higher.

The news has not discouraged Rebin.

“I am not afraid. I have no life in Iraq. No work, no future, no money. Europe is where I want to be. Germany I hope,” he said.

When the flight landed at the airport, 40 kilometers from Minsk, a border control officer in a green uniform immediately ordered all Iraqi citizens to follow him to the second floor. They emerged after two hours, and most of them boarded buses and taxis going to the large, gloomy hotels across Minsk pre-booked by their travel agencies.

A smaller group of five men, 16-year-old Afron among them, set off in pitch darkness on the six-hour walk to the city.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.