During a visit to Ukraine in 2021, I had an encounter in Lviv that left a profound impression. I met S., a young man from the republic of Chuvashia who deliberately chose not to speak Russian. Instead, we communicated in Ukrainian and Tatar. What could have led to his decision?

At the age of 16, he was convicted as an extremist for sharing memes related to Crimea and the Russian Orthodox Church on VKontakte. As soon as he turned 18, he left for Ukraine and learned Ukrainian, reserving Russian solely for conversations with his Russian-speaking Ukrainian mother. Having grown up in his father’s indigenous region of Chuvashia, S. had some knowledge of Tatar from private tutoring, given Tatarstan's proximity to his hometown.

I attempted to argue with S., emphasizing the importance of separating politics from language, viewing it solely as a means of communication. However, S. remained resolute. Instead of calling his hometown by its Russian name Cheboksary, he used the local name — Şupaşkar.

Many people depoliticize language, viewing it as nothing but a tool for communication. But under the Kremlin’s oppression, speaking the languages indigenous to Russia’s diverse regions has become an instrument of protest, as can be seen with the most widely spoken of these languages, Tatar.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the relaxation of central control from Moscow, Russia's republics experienced a brief period of national awakening. Tatarstan, in particular, gained a degree of sovereignty. People began to advocate for independence and voted in favor of it in a referendum. However, due to complex Tatar-Bashkir relations and the absence of a border with independent Kazakhstan, full independence remained out of reach.

In those 10 years, Tatar went through a period of revitalization, resulting in the emergence of activists undertaking remarkable Tatar language projects. Tatar became less marginal and more visible in public spaces, even being spoken in schools. However, by the 2000s, this momentum began to stagnate. Tatarstan's sovereignty waned, and the Tatar language was relegated to nominal status within the republic.

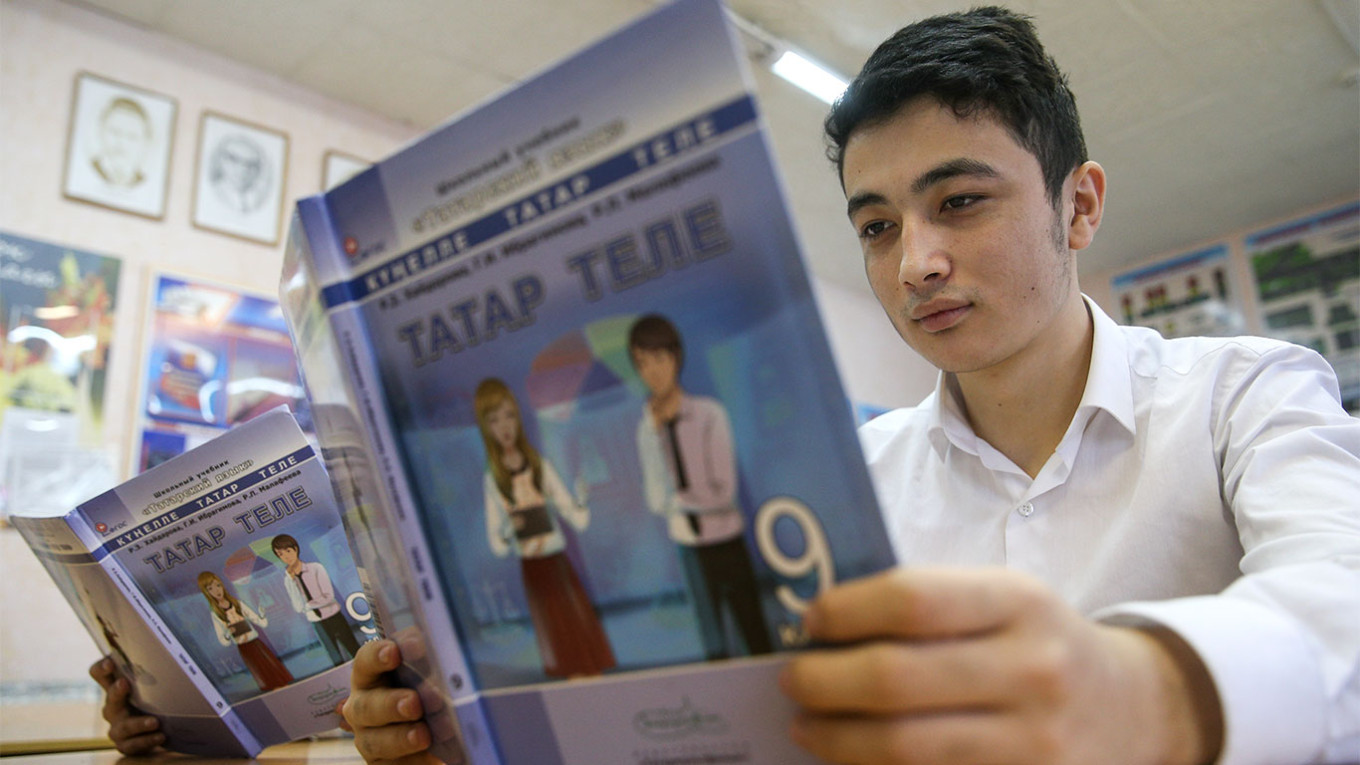

Beginning with the 2004 law that halted the shift of Tatar to the Latin alphabet and culminating 2017 legislation that rendered the study of Tatar optional, we have witnessed a gradual erosion of Tatar language rights. Notably, Tatar is a Turkic language that has been written with multiple alphabets like many other languages within the former U.S.S.R. The Cyrillic version of Tatar has faced ongoing scrutiny from linguists due to its inherent flaws. Consequently, Tatarstan made efforts to revert to the Latin alphabet in 1999, even printing textbooks for schools and universities and erecting street signs in the script.

However, President Vladimir Putin's administration perceived these as signs of separatism, leading to the introduction of a new law that prohibited languages within the Russian Federation from being written in any alphabet other than Cyrillic. This did not just affect Tatarstan. The Karelian authorities declined to comply with the law, resulting in Karelian, a Finno-Ugric language, not being recognized as a state language, firmly rooted in their refusal to relinquish their linguistic heritage.

In 2017, Russian-speaking parents from Tatarstan wrote to Putin, requesting that Tatar be reclassified as an elective subject in schools. A particularly alarming aspect of the resulting law is that Tatar schools in the republic could no longer use textbooks in Tatar. These materials must be certified by the federal Education Ministry, which faces a shortage of competent personnel for this task.

As of 2024, this certification process has stagnated, rendering Tatar schools institutions where Tatar is taught as if it were a foreign language rather than fully integrated into the curriculum. This law primarily impacts Tatar speakers, as Tatarstan remains the only place in the world where their language holds official status and is used in books, media, and government discourse. Astonishingly, even if you are pursuing a Ph.D. in Tatar language and literature at Kazan University, it is forbidden to submit your thesis in Tatar.

The law has had a direct impact on Tatar language teachers, most of whom either lost their jobs or had to retrain as Russian language instructors. The majority of schools in Tatarstan have undergone police inspections to sniff out "forced Tatar teaching."

During this period of scrutiny, the renowned Tatar writer, Rkail Zaidulla, said that while the checks should stop, the authorities clearly saw teaching the Tatar language as a “manifestation of extremism.”

Currently, the infrastructure that allows the embrace of Tatar culture to exist and develop is limited. Despite Moscow’s efforts, self-initiated schemes are developing, though they do not yet constitute major pillars of support for the Tatar-speaking population. Numerous organizations and events like Urban Tatar, Tat Cult Fest and Peçən bazarı promote Tatar culture and language in a contemporary context.

But these initiatives can also assume a political purpose, even if that was not the intent. In one notable performance, a Tatar rapper named Usal is screaming from the stage of Kazan Kremlin, “Azatqa - Azatlıq (Freedom to Azat),” referring to the Tatar political prisoner Azat Miftakhov.

Nevertheless, even these initiatives may be at risk. Using Tatar in public spaces could potentially be categorized as hate speech or extremism. There is also the potential that embracing non-Russian languages universally could lead to accusations of nationalism and Nazism. A recent example involves a Sakha (Yakut) writer and teacher, Yuri Mekumyanov, who authored an article in his indigenous language for a local newspaper on language issues and subsequently faced accusations of hate speech against Russians. Many Tatars who use Tatar in public spaces have encountered similar accusations, as doing so is considered to be unethical because not everyone can understand it.

Despite the increasing risks and oppressive measures coming from Moscow, there are no laws prohibiting the use of non-Russian languages. But in these totalitarian times, it’s important to remember that while history shows the Kremlin can crack down harder, the non-Russian languages spoken by Russia’s diverse peoples have become a powerful tool and “safe” space to express political ideas.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.