YEREVAN, Armenia – Tigran has been protesting outside the Russian embassy every day since Azerbaijan launched its offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh.

On the embassy’s steps, flowers have been laid in memory of the peacekeepers who were killed by Azerbaijani shelling last week.

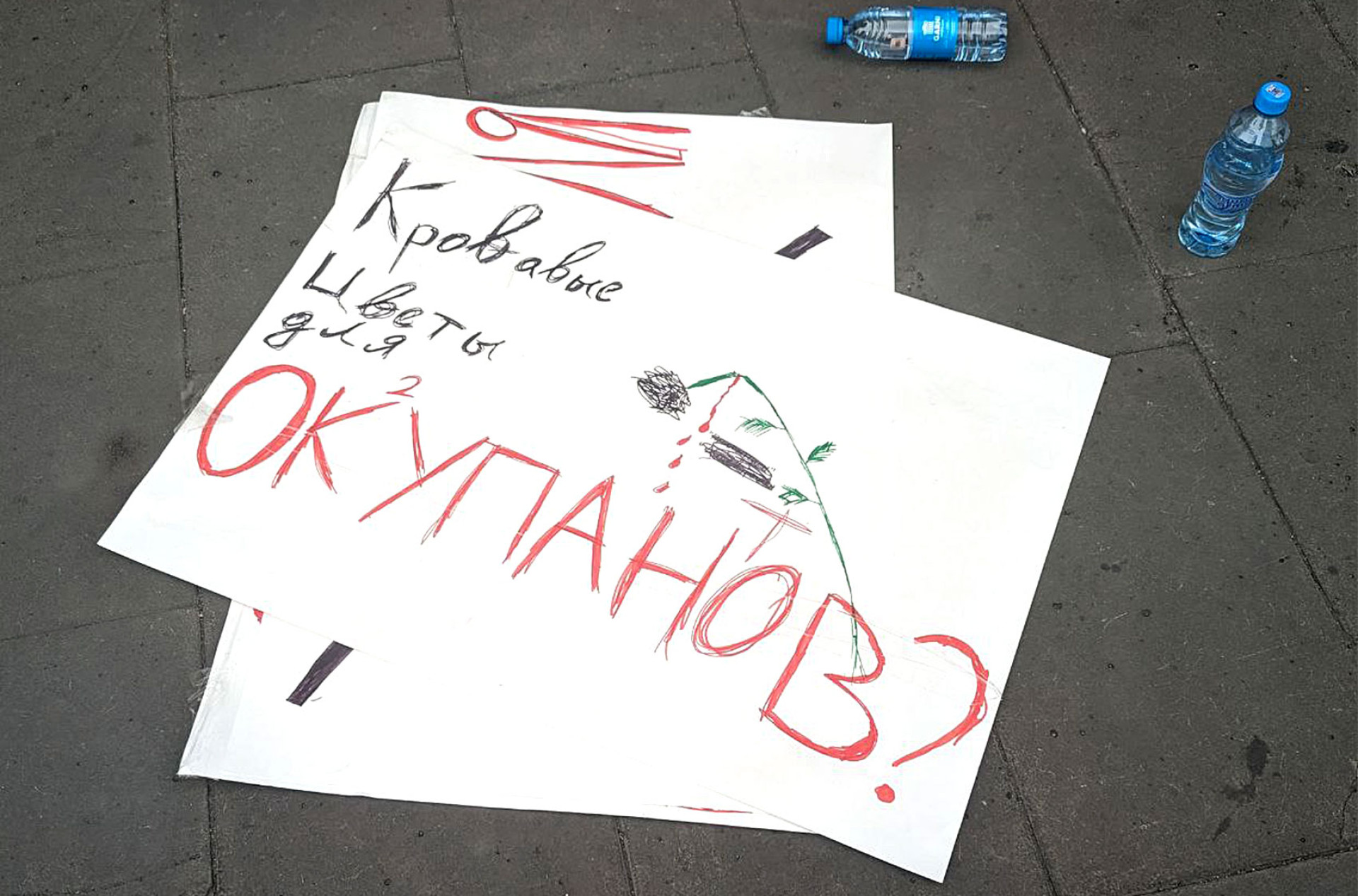

"Are these bloody flowers for the occupiers?" reads the poster that Tigran, 19, holds up. When diplomats' cars leave the embassy, he and a small group of protesters shout "Shame!"

He is just one of the thousands of Armenians who have grown disillusioned with Russia — their country’s longtime ally and security guarantor — for failing to prevent Azerbaijani aggression.

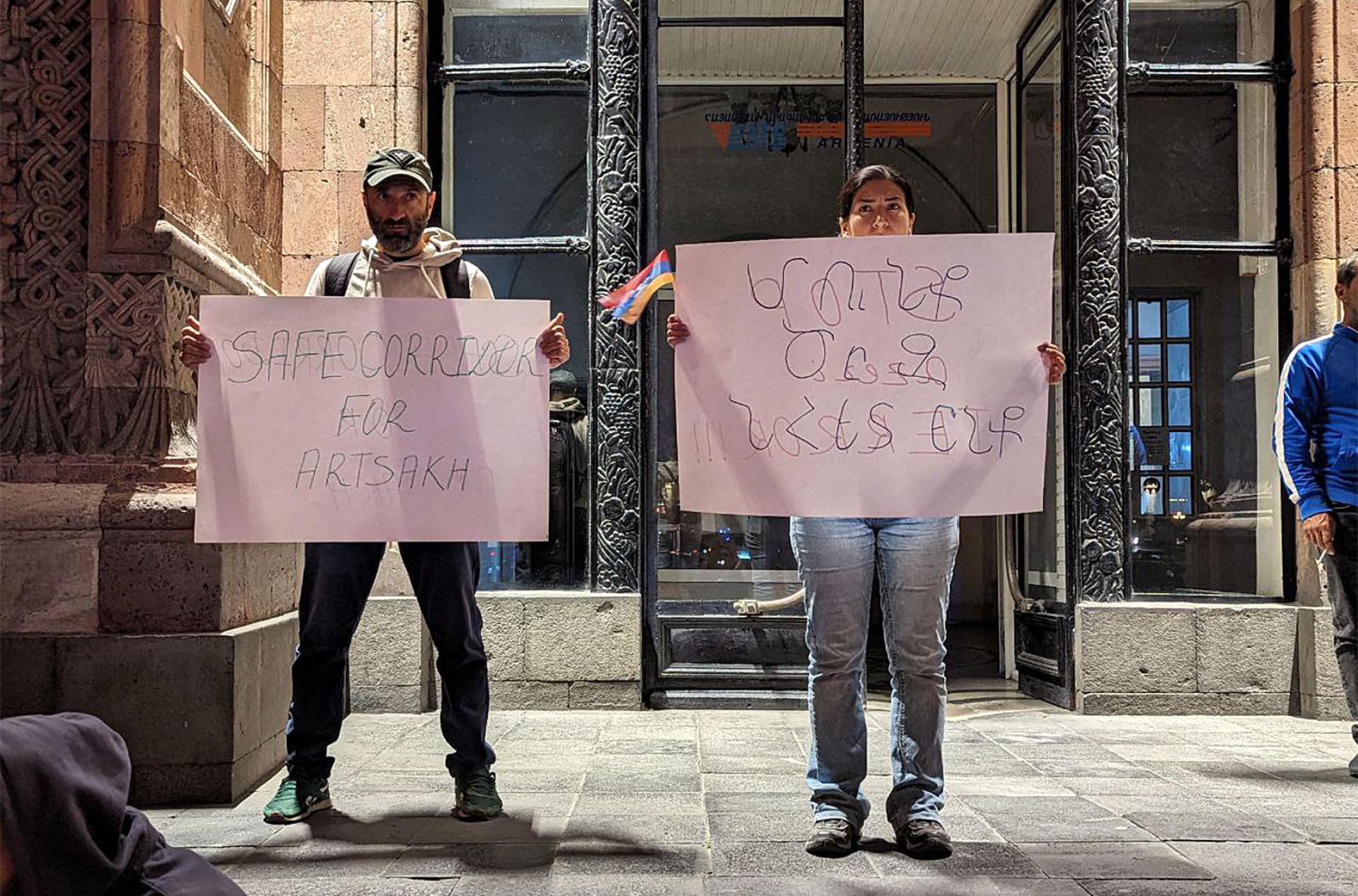

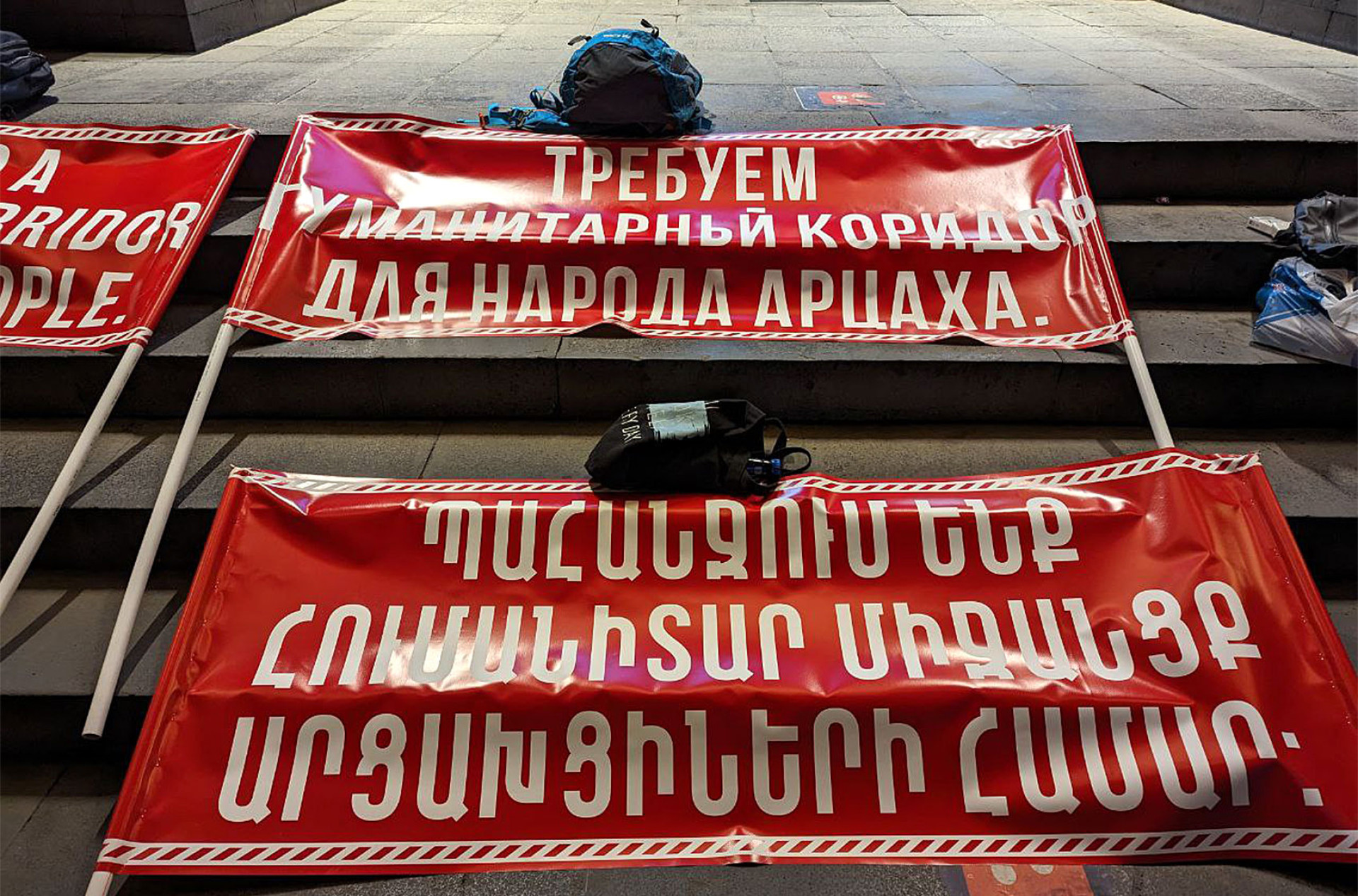

Large-scale protests have been taking place in Yerevan since Sept. 19, when Azerbaijan announced a military operation in Nagorno-Karabakh despite the presence of Russian peacekeepers in the region.

Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenian separatist leadership announced Thursday that it will dissolve, ending a bitter, three-decade fight for independence in the breakaway region, which is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan.

Some protesters accuse Moscow, distracted by its war in Ukraine, of abandoning its commitments to Armenia.

"Until recently, my whole family was pro-Russia. But our opinion has changed," Tigran, who declined to share his last name, told The Moscow Times. "Armenia has always been loyal to Russia. We are the most pro-Russia country. But now we demand from the Russian military that they do their job or get out."

Samvel, a 21-year-old student at the Yerevan University of Theater and Cinema, organized a student strike of more than 100 people originally from Karabakh.

For several days, alongside thousands of other protesters, he has demanded that the Armenian authorities save his family, who are caught in a humanitarian crisis.

“Russia promised that it would protect Artsakh,” said Samvel, using the region’s Armenian name. “People believed it and stayed there. But the Russians did not fulfill their promise. They betrayed us! Russia has stabbed us in the back.”

“We won't forget it.”

Russian peacekeepers have been stationed in the region since the end of a 2020 war between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the region that ended in an Armenian defeat.

This month, Armenia’s Foreign Ministry called on the peacekeepers to “take clear and unequivocal steps to stop Azerbaijan's aggression.”

But Moscow merely urged Baku and Yerevan to put “an end to the bloodshed... and a return to a peaceful settlement" as Russian peacekeepers largely stood aside.

Last week, Baku announced an end to its military operation after the Armenian separatist forces agreed to lay down their arms and hold reintegration talks.

And on Sunday, Karabakh’s 120,000 ethnic Armenians began embarking on a mass exodus from the region, fearing ethnic cleansing by incoming Azerbaijani forces.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said the day before that his country would welcome the arrival of those displaced from the territory, and by Thursday, more than 68,000 refugees had already arrived in Armenia.

Because the latest ceasefire agreement was brokered by Russian peacekeepers, some Armenians suspect that it was in fact a "deal" between Moscow and Baku.

Soon after, the National Democratic Alliance, a pro-Western political movement, organized protests in Yerevan. Hundreds marched through the streets of the Armenian capital for several days in a row, holding torches and chanting "Russia is the enemy!"

Although Tigran said he believes the fall of Karabakh’s separatist government has undermined the confidence of many Armenians in Russia as an ally, he admitted that a significant part of society blames the loss on Pashinyan, who has moved away from Moscow in recent years.

"I think Russia is still supported by about 40% of Armenian society," he said.

"But I think many of them just haven't had time to be disappointed yet."

According to a May 2023 survey conducted by the Washington-based think tank International Republican Institute (IRI), 50% of Armenians described their country’s relationship with Russia as “good,” the lowest ever measured in an IRI poll in Armenia.

Nevertheless, the majority of respondents indicated that Russia is still one of Armenia’s most important political, economic and security partners.

And despite the widespread criticism toward the Russian peacekeepers, many Armenians still believe the situation in Karabakh could have been much worse without their presence.

Since the start of the crisis, the Russian Defense Ministry has published daily reports on its delivery of humanitarian aid and helped escort Karabakh Armenians. Videos published by the ministry show women thanking Russian soldiers.

The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic gained de facto independence from Azerbaijan in 1994, after more than two years of war that ended in Yerevan’s victory over Baku.

A second bloody war over the region in the fall of 2020 saw Azerbaijan regain part of the territories it had lost in 1994 and ended in a Russia-brokered ceasefire.

In November 2022, as tensions with Azerbaijan escalated again, Yerevan was denied its request for military assistance by the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), drawing criticism from Pashinyan.

In a sign of the Armenian prime minister’s growing frustration with the Kremlin on the issue of Karabakh, Armenia and the United States earlier this month carried out joint military drills, which drew the ire of the Russian authorities.

Armenia’s pro-Russian opposition laid the blame for the loss of Karabakh on the prime minister, accusing him of betraying the region’s ethnic Armenians “in favor of the interests of the West.” Mika Badalyan, a political activist who regularly appears on Russian television, called on Armenians to take to the streets and overthrow Pashinyan's government.

Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova said Russian peacekeepers would help Karabakh Armenians in every way possible, while the U.S. and the EU, she argued, “treat Yerevan with destructive fanaticism, pushing Armenia to withdraw from the CSTO.”

"The fact that Pashinyan began to move away from such an ‘ally’ as Russia does not mean that we will begin to cooperate with the West. They don't expect us there either, to put it mildly. And this is understandable to many,” said Ani Sargsyan, an entrepreneur who raises humanitarian aid for refugees.

“But the fact is that it will no longer be possible to follow the same path with Russia and continue friendly relations. Relations have deteriorated not only because of Pashinyan. And here we must admit that it seems that we are moving away from Russia,” she added.

Arevik, a 24-year-old volunteer collecting humanitarian aid, said she was certain that the refugees would never return to Karabakh.

“No one will live there. And the Russian troops will leave,” she said. “But I am afraid that [Azerbaijani President Ilham] Aliyev will not stop there. He once said that the whole of Armenia is just Western Azerbaijan.”

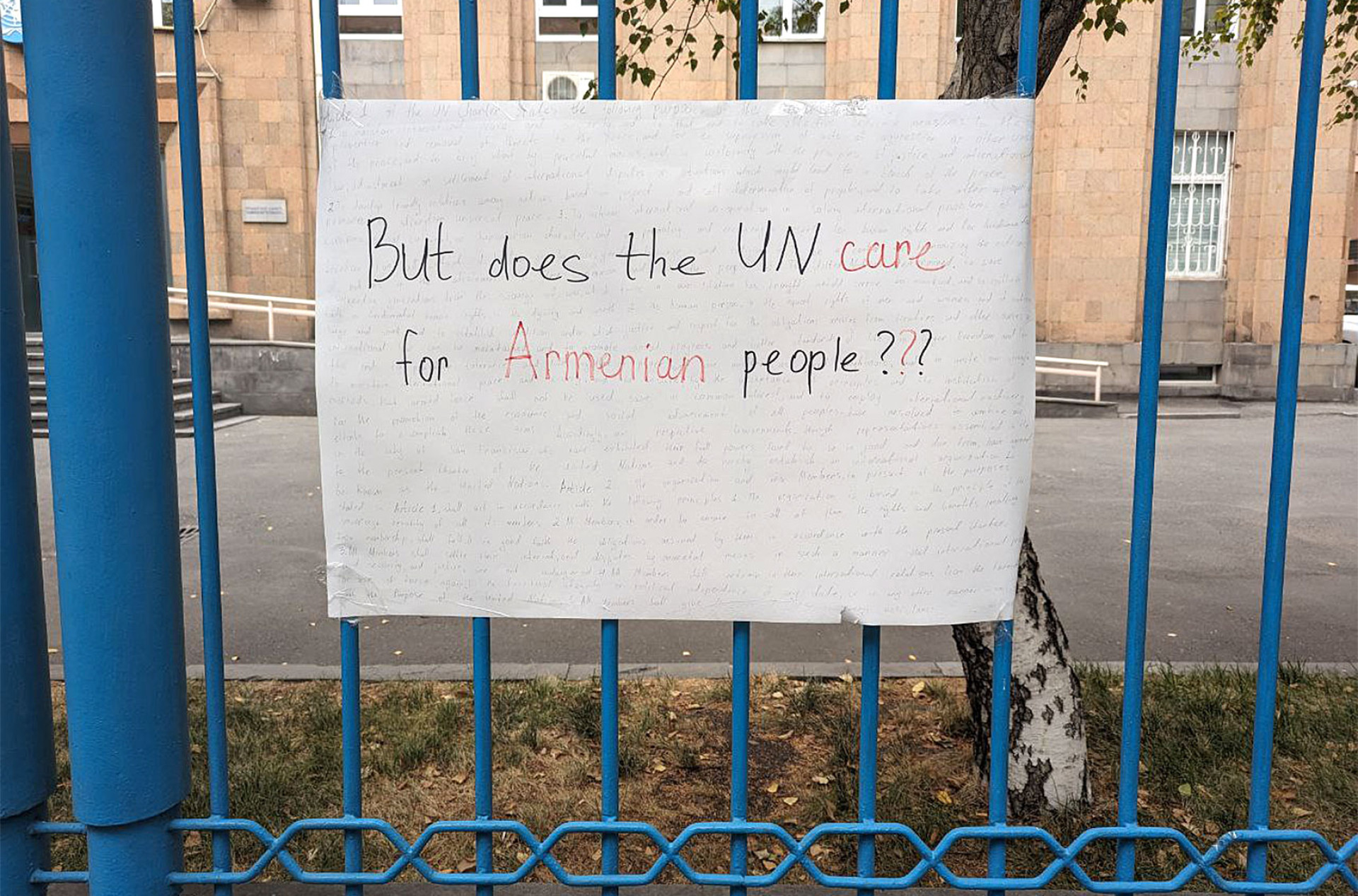

“We shouldn't expect someone to protect us. It was immediately clear that Russian troops would s*** themselves in Karabakh. And international organizations just don't care about us,” she added.

“Unfortunately, we are not Ukraine. It is unprofitable to protect us.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.