Would you sell your soul for a cookie? Russians like cookies so much that the authorities believed a person would sell out his homeland for a cookie. In 1933, the Soviet writer Arkady Gaidar wrote about a heroic Pioneer and a bad boy who committed treason in return for payment of a jar of jam and a basket of cookies.

Today Russian propaganda writes constantly about the U.S. State Department's cookies, which are supposedly used to seduce people into opposing the war and Putin's government. This story began when U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland handed out sandwiches, bread rolls, and pastries to people protesting on the Maidan in Kyiv in February 2014. The Russian media, however, wrote that she handed out cookies.

But it's true: Russians have long loved cookies and they still do to this day. Cookies were very popular in the Soviet Union. Throughout the entire Soviet period you could always find an oblong yellow-red package of cookies called "Jubilee" that were made by the aptly named Bolshevik Factory. So what was the jubilee that this popular Soviet food was named after? Actually, it was a little secret that was not discussed in those years. The cookies quickly became popular and the authorities didn’t pay much attention to the name at first — who cared what jubilee the cookies were made to celebrate? It turns out that they were made to celebrate a jubilee marked all through the country just before Soviet power.

Oddly enough, the cookies were made for the anniversary of... the House of Romanov! Confectioner Adolf Sioux came up with a recipe of wheat flour, cornstarch, powdered sugar, margarine, milk and eggs to mark the 300th year of the royal dynasty. The Jubilee cookies were presented to the Romanov family and rumored to have been enjoyed by the emperor himself. The A. Sioux and Co. Factory was named a supplier to His Imperial Majesty's Court.

Above left: "Ahead of Everyone," a pre-revolutionary advertisement for Sioux factory cookies; above right: a 1920s Soviet poster, "I Eat Cookies from the Red October Factory (formerly Einem)

On December 4, 1918, Lenin signed a special decree to nationalize the factory, and after the death of the leader of the world proletariat, it was given the honorary name "Bolshevik." And that was the start of the Soviet chapter in the life of Jubilee cookies. Until 1927 the factory produced soap and perfumery along with cookies, galettes and wafers. In the 1960s, along with another Moscow confectionery factory Krasny Oktyabr, it was one of the largest in Europe.

Actually, historical parallels with cookies haunt us. Take the word тунеядец (freeloader, lazybones, do-nothing). In the Soviet sense, it meant a parasitic existence at the expense of society. According to an article of the Criminal Code (abolished only in 1991), being a freeloader — when an able-bodied adult didn’t perform socially useful work but lived off income that did not come from labor — was a crime punishable by law.

The famous poet Joseph Brodsky was especially familiar with the word. In 1964 he was sentenced to five years in exile in a small village in the Arkhangelsk region for being a freeloader. Memories associated with the word probably came back to him long after he left the Soviet Union. But as he sat in an Italian restaurant or café, he never would have imagined how his way of life as a young man in Leningrad and Russian cuisine could come together.

Below: Joseph Brodsky in exile and the article “The Trial of Freeloader Brodsky” in the Vecherny Leningrad newspaper (1964).

Meanwhile, we can find cookies with exactly this name — Freeloaders— in “Russian Cookery” from 1795:

Take a pound of butter, flour, cinnamon, sugar, and almonds. Mix all this and knead the dough on the table. Roll it out. Use a cutter to form shapes and place in a “freely breathing oven” [in an oven that has cooled down after baking bread]

How can this be? What do cookies and a lazy person have in common? The explanation is simple. The word тунеядец (freeloader) is a synonym for “idler” or “lazybones.” The word “lazy” is frequently used in Russian cuisine — for example, lazy cabbage rolls, lazy cabbage soup. It means a dish that does not require much work. And it’s true: This recipe is really very easy.

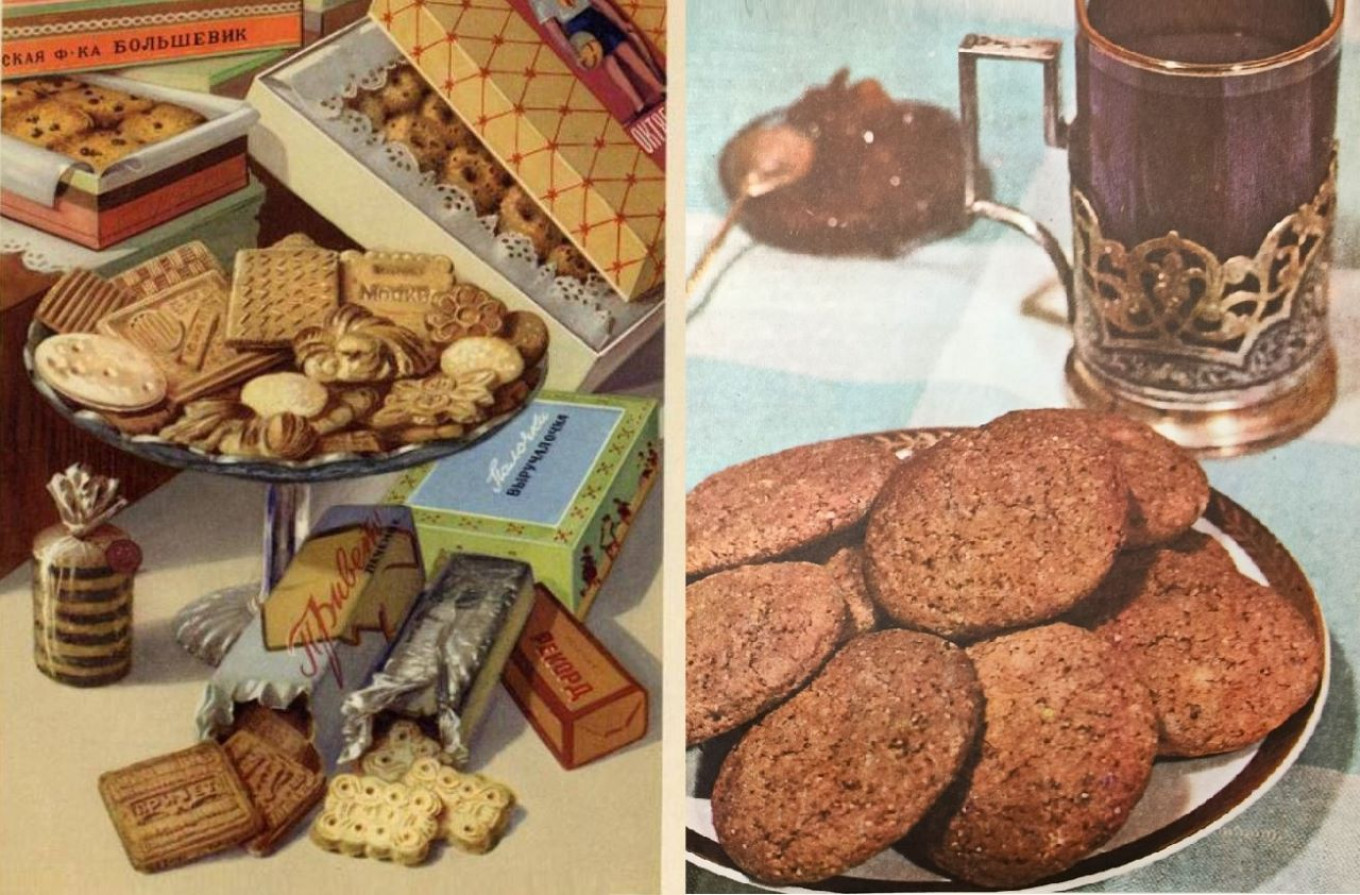

Another iconic Russian treat is the oatmeal cookie, which became especially popular in the Soviet period. Its unique flavor, intense brown color, slight cracks and crumbly texture are still remembered fondly by our contemporaries. Oatmeal cookies have been made in Russia since the middle of the 19th century, which is when bakers began to add sugar. Before that oatmeal dough was not sweetened or leavened but baked as a flat bread. Now it was a dessert.

In tsarist Russia, the main producer of oatmeal cookies was St. Petersburg. Cookies from the city on the Neva River were the most delicious. Everyone who went there considered it his duty to take back home this crumbly confectionery. They were served at tea parties, which were very popular at the time.

This love continued in the Soviet period — only now Moscow became the place for oatmeal cookies. Every business traveler brought back from the capital the long cardboard pack containing 20 round, brown cookies. By the way, the famous "Tasty and Healthy Food Book" called them “dietary baked goods” and recommended them for children and convalescents.

Oatmeal cookies are a favorite treat for millions of people from many countries. There are so many variations: made with whole oat flakes, peanuts, nuts, raisins, coconut, banana, salt, etc. All of these recipes are delicious in their own way and certainly interesting. But the soul of everyone with a Soviet past lies in these good old cookies.

Here is one of the best recipes for these cookies, close to the cookies of our childhood.

Oatmeal Cookies

Ingredients

- 200 g (¾ cup + 2 Tbsp) butter

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 2 eggs

- 1 1/2 cups flour

- 3 cups oatmeal

- 1 tsp baking soda

- 1/2 tsp salt

- 1 cup of raisins or nuts

- Vanilla and cinnamon (these are essential — - they are what gives the right flavor to the oatmeal cookies)

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 180°C/ 350°F.

- In a separate bowl beat the butter and sugar until frothy and white, then add the eggs, one at a time.

- Add vanilla to taste.

- In a separate bowl mix the flour, oat flakes, baking soda, salt, raisins, cinnamon.

- Combine with the egg and butter mixture. Mix thoroughly.

- Using a teaspoon drop cookie dough on a baking tray lined with baking paper or greased with oil.

- Bake for 18 to 20 minutes.

That's it — and you have delicious cookies for tea or coffee on your table.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.