How serious is cooking? Certainly many people think that the kitchen is no place for jokes and pranks. But today, on April Fool's Day, we simply must take a closer look at the humor and fun that we find even in such an important matter as culinary history.

Foreigners' acquaintance with Russian cuisine has always brought a smile. Today the Internet is full of videos of Italians or French people sampling “herring under a fur coat,” okroshka, or meat aspic. They aren’t just having a good time, they are laughing so hard they can barely eat or speak. And actually that’s the way it was many centuries ago, too. But to be honest, Russians themselves also had a lot of fun.

Deceiving gullible listeners — especially foreigners — is a longstanding hobby of our compatriots. And it seems that our forefathers had a good time, too.

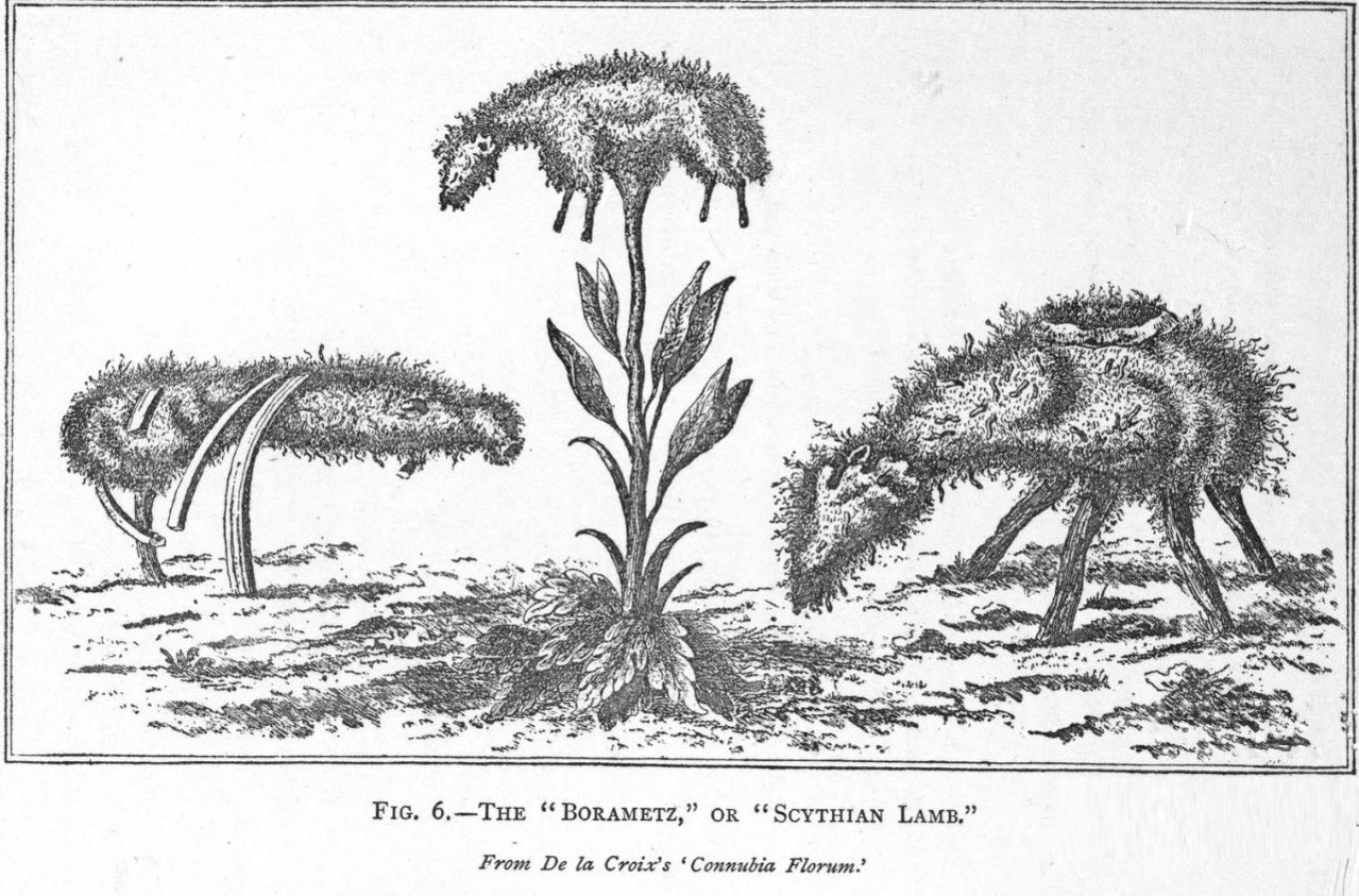

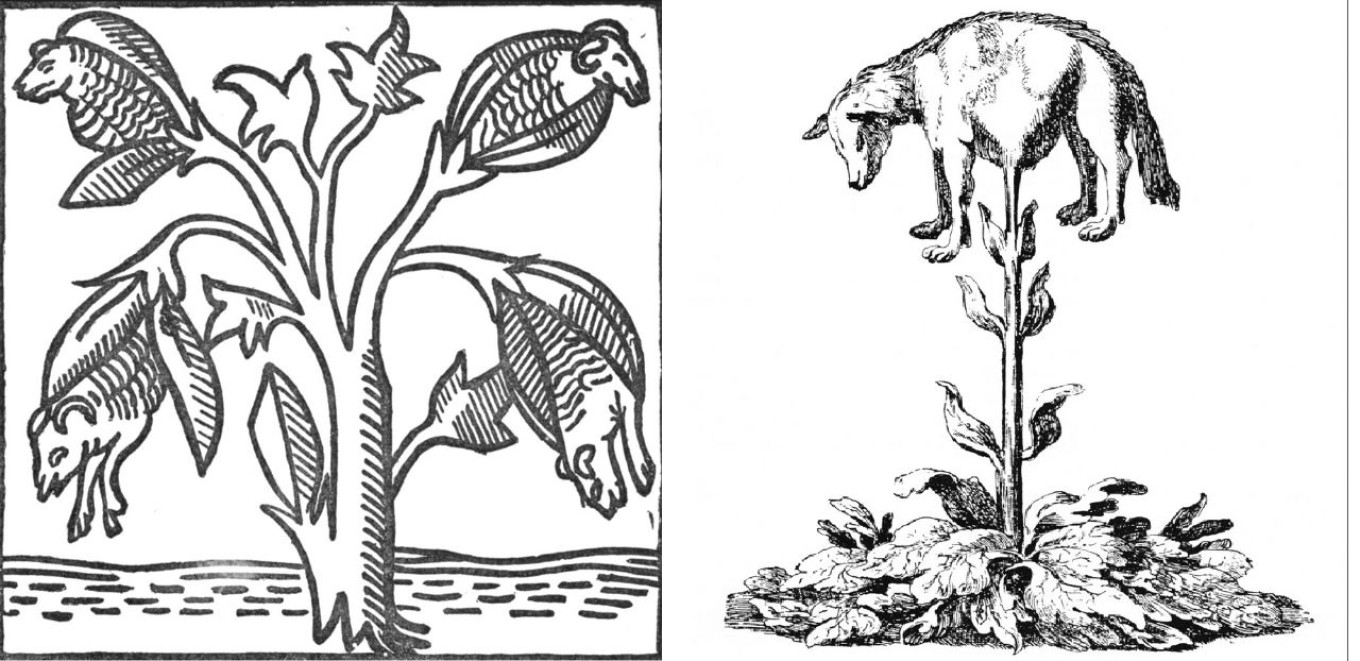

Borometz is one of the oldest and funniest myths about Russia and Tatary — as Russia was called about 500 years ago in Europe. What is it, you ask? It is so horrible you won't believe it!

Borometz (aka Barometz and Borametz) is the "Vegetable Lamb of Tatary." It is a plant that produces fruit — sheep — that are joined to the plant by an umbilical cord that allows it to feed on the grass around the plant. When the lamb eats up all the grass, the sheep and plant die.

Adam Olearius (1599-1671) was one of the Western European travelers to write about this amazing animal-plant:

"They also told us," Olearius wrote, "that there, beyond Samara, between the rivers Volga and Don, grows a rare kind of melon, or rather a gourd, which resembles a lamb, and the Russians therefore call it baranets (Boranetz). The Russians say that this melon eats grass. When the fruit ripens, the stem withers, but the fruit itself is covered with curly wool like that of a lamb, and this wool, they say, can be dressed and prepared for use against the cold. In Moscow they showed us a few pieces of this wool torn from a blanket, and told us it was the wool of melon baranets.”

Above: Baranets. Illustration from: The Travels of Sir John Mandeville (1357 -1371) and Specula Physico-Mathematico-Historica Notabilium ac Mirabilium Sciendorum, in Qua Mundi Mirabilis Oeconomia. Norimbergae, 1696.

Another traveler, Jacob Reutenfels, who visited Moscow in the 1670s, reported the following:

"... Between the Volga and the Tanais there is a famous plant. Its bark resembles a sheep's skin; this fleece is carefully removed, and the nobles pad their dresses and mittens with it to make them warmer. It has the ability to dry and warm things, and it dries all the grass around it before it withers. This is why some people who are poorly informed believed that it has a mind.”

The Dutchman Jan Struys, who visited our country during the reign of Peter I, wrote about this plant, too:

"To the east of the river there is a large desert steppe. In this steppe sheep also grow. They grow as a fruit the size of a pumpkin. The fruit looks like a ram, with head, feet and tail, hence its name. Especially remarkable is the skin, which covers the outside of this plant. It is shiny white wool that is very fine, as thin as silk. These skins are very highly valued by the Tatars and Russians, and I myself have seen them on sale and learned about them ... In addition, it is reported that wolves like this lamb very much. And that it has meat, blood and legs."

Tales about this amazing plant were fed to foreigners in Russia for a long time — over several centuries. Perhaps this entertainment was passed on from generation to generation. The tellers of these tales took the effort to show the foreigners bits of wool from the plant and sell it to them. Our native storytellers certainly had a lot of fun, and for years later everyone laughed at the gullible foreigners. Too bad we don’t know who invented these stories to begin with.

In the 19th century, the adventures of foreigners in Russia continued. A symbol of their lack of understanding of Russian life and cuisine was the expression "under the spreading cranberry tree.” The "spreading branches of the cranberry" is now a phrase referring to tall tales and untruths that reveal the speaker or writer’s ignorance of his subject.

According to one version, it came from a description of Russia in which the ignorant French author writes that he sat "under the shadow of a majestic cranberry" — sur l'ombre d'un kliukva majestieux." Of course, a ground-hugging cranberry bush (2-3 cm off the ground) cannot be a majestic cranberry tree. Whether the expression had a real foreign author is still a matter of debate among historians. However, the phrase itself has become a classic in Russian literature.

But the author of another funny passage about Russia is known with all certainty. In his travel sketches Alexandre Dumas (père) made some of his readers laugh by his use of imaginary Russian names. The women in his novel "Mémoires d'un maître d'armes, ou dix huits mois à Saint-Petersbourg" bear the names Teljatine [телятина — veal] and Telegue [телега — cart].

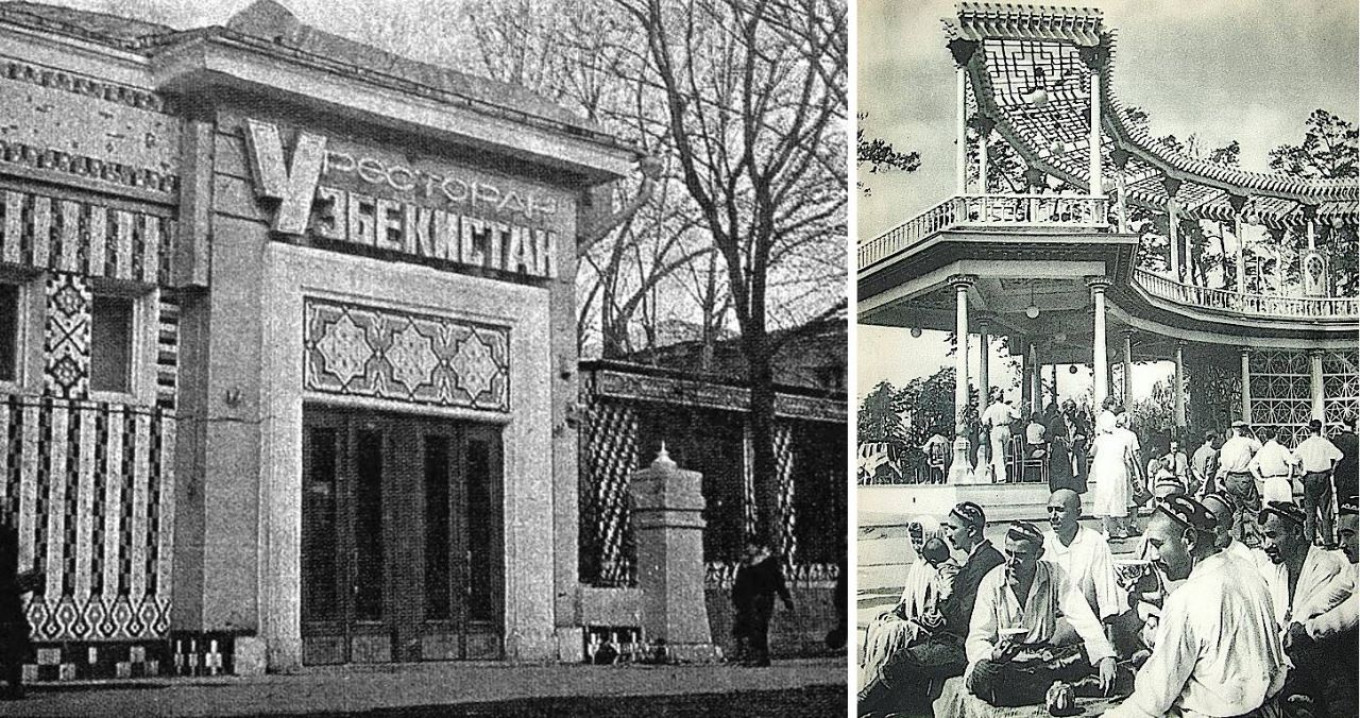

But hoaxes were created in Russian cuisine not only by foreigners and for foreigners. The Soviet era also brought a lot of confusion to our cooking. For example, take the Tashkent salad, which you can order to this day in any Moscow restaurant where Central Asian cuisine is served. Only in the city of Tashkent, no one has ever heard of this supposedly ancient dish.

The 1960s was the heyday of Soviet cuisine. That's when the authorities decided to achieve a synthesis not only the cultures of different peoples, but even their cuisine. Numerous restaurants of the Soviet republics opened in Moscow: restaurants called Baku, Minsk, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, and Vilnius. The old Georgian restaurant Aragvi, which had once fallen into disrepair, got a new lease on life.

Although the menus of these restaurants presented the "native" dishes of the republics, in fact they were often adapted to standard Soviet tastes. This was true even for the republics of the European part of the U.S.S.R. And for the Asian republics, sometimes new dishes were created that combined some national tradition with the average metropolitan chef's views. Well, really, what’s a chef to do when traditional Uzbek cuisine has no salads in the European sense of the word?

True, in Uzbekistan they eat an appetizer of green radishes dipped in suzma (a salted fermented dairy product, similar in appearance to pot cheese). But this is impossible to imagine in a Moscow restaurant. And so the amazing Tashkent salad was developed, a hybrid of the traditional Central Asian dish and "Stolichny" salad (Soviet salad Olivier) — just the thing to suit public catering services.

“What do you eat instead of salad Olivier? What do you have with your first shot of vodka?” Uzbek chefs were asked in Moscow.

“We eat green radishes — they’re delicious. Also cold meats, boiled or roasted. And suzma with herbs and green radishes. That’s what we start with.”

And with that culinary information, an international team of chefs began to invent a “traditional Uzbek salad.” “Boiled meat — that’s good. Green radish? Let’s cut it julienne. What’s that ‘suzma’ stuff you mentioned? Some kind of soured milk? No, that won’t work for us — it will go bad too quickly. We’ll dress it all with mayonnaise.”

And that’s how Tashkent salad appeared. It was the perfect dish for public cafes and restaurants: simple, easy to make, long-lasting under refrigeration and no need for high-quality ingredients — you can’t see anything under all that mayonnaise. And so the traditional Uzbek appetizer of sliced green radishes, boiled meat and suzma was transformed into this now classic Soviet salad.

Another turn in the twisted history of deception and hoax in Soviet cuisine.

Tashkent Salad

Ingredients

- 500 g (just over 1 lb) green (Margelan) radish

- 200 g (just under ½ lb) boiled beef (or boiled tongue)

- 2 medium onions

- 1 Tbsp vegetable oil

- 150 g (just over ½ c) sour cream

- salt, pepper to taste

- If desired: 2 hard-boiled eggs and fresh herbs

Instructions

- Boil and cool the beef or tongue.

- Slice the onions into half-rings and fry until golden in hot oil.

- While the onion cools, cut the radish into a fine julienne or grate it on a special Korean grater. You can, of course, grate it on an ordinary grater, but the radish will give off so much juice that the salad will literally float in liquid. In any case, after grating the radish, place it in a towel or take handfuls and firmly squeeze out all the liquid.

- Cut the meat or tongue into small strips and mix all ingredients: radish, fried onions and meat.

- Season with salt and pepper and dress with sour cream. The salad can also be dressed with mayonnaise or a mix of mayonnaise and sour cream.

- When serving, garnish with hard-boiled eggs cut in quarters, sprinkle with greens.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.