Every Friday, the Russian internet — well, its liberal part at least — waits with bated breath for communications regulator Roskomnadzor to announce which Russian citizens have been deemed "foreign agents" that week. "Who will it be today?" we wonder.

This peculiarly Russian phenomenon might need some explanation to those not used to Russia's 21st-century reality. What exactly does it mean to be labeled a foreign agent in today’s Russia, how is it that any organization or individual can now be added to this effective blacklist, and why does the Russian government require so many internal enemies?

Russia's law on foreign agents was passed over a decade ago to stigmatize foreign-funded nonprofit organizations engaged in activities that could be seen as political.

To many at the time, this absurd example of government overreach appeared to be a mistake, with the Justice Ministry seemingly equating any form of civic action as political activity, whether that be campaigning against deforestation or protesting domestic violence. Any organization independent of the state was potentially a candidate.

But, as we all now understand with terrible clarity, the introduction of the law was no mistake. In fact, it was just the beginning.

In 2017, the law was expanded to include the media, then in 2019 to allow the status to be given to individuals.

Last month, the requirement for a foreign agent to be a recipient of foreign financing was eliminated. Now, all that's needed for a person to be deemed a foreign agent in Russia is for the government to decide that they’ve come “under foreign influence" — a purposely nebulous term that has transformed the law into a powerful weapon for silencing the Kremlin's critics.

Those labeled foreign agents face significant consequences in their day-to-day lives, being disqualified from receiving any state funds — including child benefit or income support — as well as banned from teaching at schools or state universities, working for the Russian state or municipal bodies, being members of electoral commissions or contributing to expert bodies. Foreign agents are also prohibited from enlisting in the military but — and get ready for this — they can still be drafted in the event of mobilization.

In addition to that, the state can conduct unrestricted searches of their homes and request information about their financial and economic activities from banks and government agencies without a warrant. Banking becomes far harder too, and foreign agents are even banned from using Russia's simplified tax system, a sanction that seems deliberately mean-spirited.

To cap it all off, any publication or social media post by a foreign agent must be accompanied by an irritating disclaimer typed in block capitals to ensure that anyone innocently browsing the content is immediately made aware that its author is an outcast from society.

Threatening ostracization as a means of combating dissent is a well-established phenomenon in Russia and was widely used during the Soviet era when an entire category of citizens was deprived of their basic civil rights and denied even the right to vote.

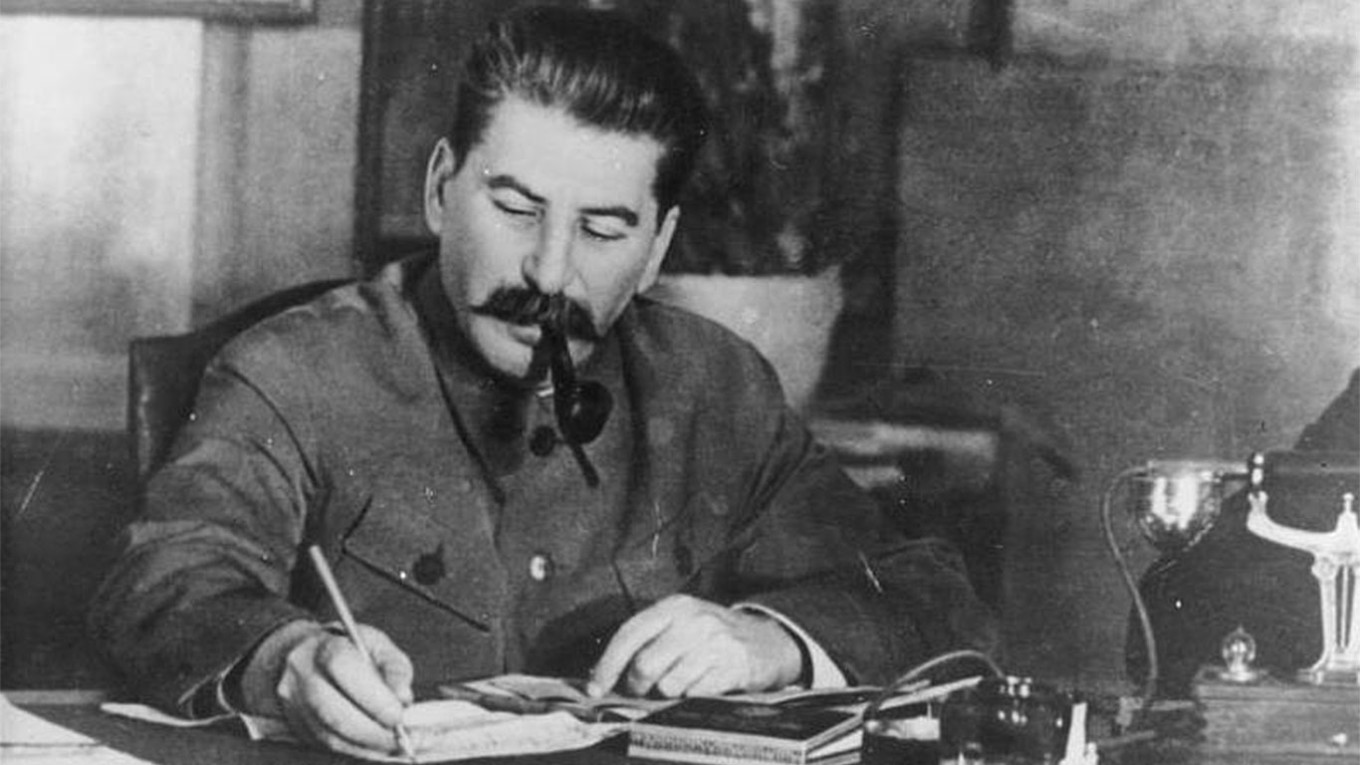

The term “foreign agent” was used by both the Bolsheviks and their Soviet successors to intimidate dissenters and to put a “black mark” on their political opponents, which usually meant their arrest would soon follow.

By 1930, the term “foreign agent” was being used routinely by Stalin as a tool to crush anyone who opposed his dictatorship.

The constant talk of foreign agents disappeared from the Soviet press after Stalin's death and Nikita Khrushchev's subsequent denunciation of the Great Terror. And yet, none of that prevented Russia from resurrecting the “enemy within” narrative over half a century later.

So why is Russia always looking for an internal enemy? The answer is perhaps striking in its simplicity — biology is to blame. The presence of an external enemy, an “alien,” is necessary for the sustained existence of even the simplest communities.

The Austrian zoologist Konrad Lorenz demonstrated that the mechanisms of “friend” and “foe” recognition are inherent at all levels of biological evolution. Bacteria break down environmental components into two categories, attractive and repulsive, each of which generates a standard behavioral response, while geese innately know that “everything red, big, and furry is very dangerous.”

But what if there is no obvious external enemy? In that case, it's not uncommon for ecosystems to fail. An example of this cited by Lorenz describes the behavior of male fish who, in the absence of an external rival encroaching on their territory, transfer their aggression to their own offspring and destroy them.

In the Kremlin's worldview, no challenge to its power — let alone a revolution — can be domestically generated, and thus any act of defiance against Putin’s rule must be the result of foreign interference.

Kremlin ideologues have in recent years been pushing the narrative that the Russian nation has a natural enemy in a group of people it calls Anglo-Saxons, though these mythical creatures can't be said to correspond to the historical Germanic tribes that invaded and settled England in the 5th century.

It seems that even the Kremlin doesn't fully understand who the Anglo-Saxon enemy really is. What's more, the term Anglo-Saxon is increasingly used as a synonym for “fifth column” and can potentially include anyone in Russia sympathetic to the collective West, making it a qualifier of political belief rather than ethnic identity.

Russia's endless search for an enemy has finally borne fruit then, and the confirmation of the enemy's existence alone has proven sufficient to rally a significant part of the Russian population around the flag.

But let's assume for a moment that Putin and his henchmen are right and that there really are enemies among the Russian population acting on behalf of Western intelligence. It then stands to reason that the phenomenon is one that has come about since Vladimir Putin came to power. In 1999, before Putin was president, most Russians found it difficult to say who Russia's enemies were when asked.

However, by the watershed year of 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and Russian separatists began fighting in eastern Ukraine, 84% of Russians said they were certain that Russia’s enemies existed.

This article is an edited version of a video explainer by media collective Prodolzhenie Sleduet.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.