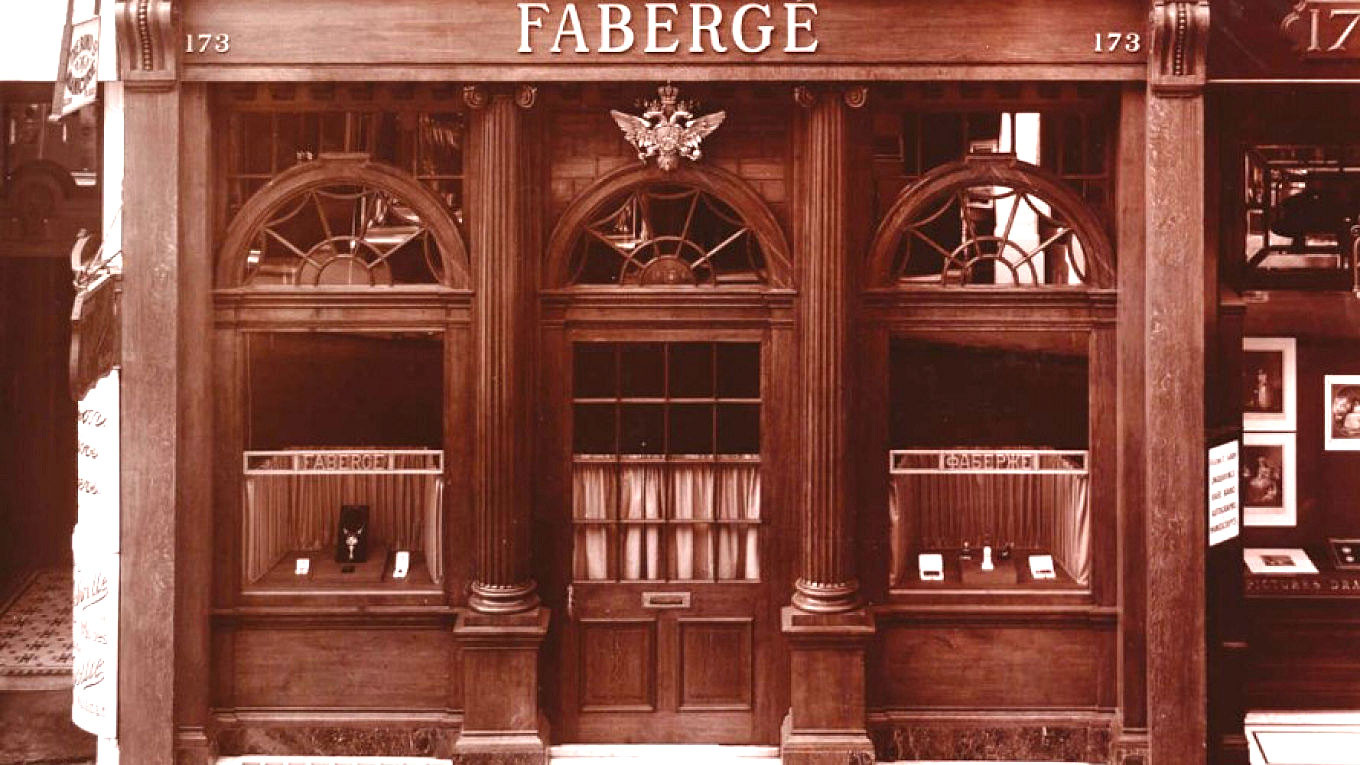

LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM — “Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution” is the Victoria and Albert Museum’s third exhibition dedicated to the Russian goldsmith. A show in 1977 was the first major exhibition on Fabergé to be held by a national museum in the United Kingdom. The second exhibition was co-organized by the V&A, the Fabergé Arts Foundation in Washington, D.C., the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. The current exhibition sets out to spotlight the firm’s little-known London branch, the only one to operate outside the Russian Empire.

The title is something of a misnomer, since the exhibition charts the whole of Fabergé’s career with a significant portion of the space dedicated to the firm’s defining — even intimate — relationship with the Russian imperial family. The operations and clientele of the Bond Street branch do receive significant attention, but perhaps not enough for them to headline the show.

The exhibition showcases the adaptability and sheer artistic range of Fabergé and its artisans. The chronological and geographically delineated layout allow visitors to see the immense variety of objects produced by the firm beyond the famous Easter Eggs, from enamel cigarette cases to a medal commemorating the Year of the Pig commissioned for the Royal Court of Siam.

The shift in aesthetic from the pieces made for the Russian aristocracy to the British aristocracy is striking. While the Russian pieces are not devoid of kitsch — the hardstone sculptures of the Kamer Kazaks (Chamber Cossacks), personal bodyguards of the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna and the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna being notable examples —the British aristocracy had a taste for sculptures of their pets and racehorses from precious stone. The quartz and sapphire sculpture of King Edward VII’s prize-winning Shire horse Hoe Forest King is a fine example.

The V&A is no stranger to blockbuster exhibitions, but the fact that this particular one is almost completely sold out raises the question of whether the enduring appeal of Fabergé in the West is still motivated by a subconscious fetishization of Russia. The dazzling beauty of the pieces on display does, after all, play into a Western conception of Russia as the grand and distant land of tsars and autocrats.

However, a less problematic explanation for the exhibition’s appeal is the fantasy-like escapism it offers from the grim 21st century reality of a global pandemic and economic instability.

Even for aficionados of Russia’s pre-revolutionary history, the exhibition offers something new. Such surprises include the pieces made by the firm for the Siamese royal family. Carl Fabergé’s son Nicholas brought the firm’s wares first to King Rama V and then to his son, the English-educated King Rama VI. Pieces such as the green nephrite buddha are fascinating examples of how the artisans of Fabergé could adapt to the particular cultural and artistic traditions of their clientele.

For a firm so adept at adaptation, the exhibition’s penultimate section, which focuses on the impact of the First World War and the 1918 revolutions, is particularly poignant. For decades it had flawlessly changed its colors to suit its surroundings. The Great War and then the October Revolution, however, finally gave birth to a world to which the artistic chameleon could not adapt. Although it tried by creating more austere pieces, such as bronze and silver plates and even real bullets for the Imperial artillery, the firm — by then a byword for nobility and extravagance — could not survive in the harsh new modernity that emerged after 1918.

The final room, dedicated to the iconic Imperial Easter Eggs, offers a redemptive ending to the exhibition’s ‘rise and fall’ narrative. The anticipation makes the reveal all the more climactic. In a black box of a room stand brightly illuminated glass cases that both literally and figuratively place the eggs upon a pedestal. With gentle piano music playing in the background, the atmosphere is one of wonder. One of the most stunning pieces is the Winter Egg containing a basket of wood anemones commissioned by Tsar Nicholas II for his mother, the Dowager Empress. This seasonal confection was the brainchild of Alma Phil, one of Fabergé’s only two female designers. The subdued color scheme, the delicate silver fronds representing frost, and the fragility of the glass structure are enough to literally send shivers down the spine. The glory of the House of Fabergé, the exhibition’s crowning display seems to say, lives on even if the firm itself does not.

It is, perhaps, symbolic, if unintentionally so, that this great display of luxury should be held in the heart of Kensington and Chelsea, the upscale London borough famously home to money both old and new. Since the early 2000s, it has also been known for its wealthy Russian residents. Were he here to see it, Fabergé himself might be rather pleased to see his work once again at the heart of a milieu known for luxury even if, these days, the pieces are for looking, not for buying.

The exhibition runs until May 8, 2022, in Gallery 39 of the Victoria & Albert Museum. For tickets and more information about Fabergé and the exhibition, see the museum site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.