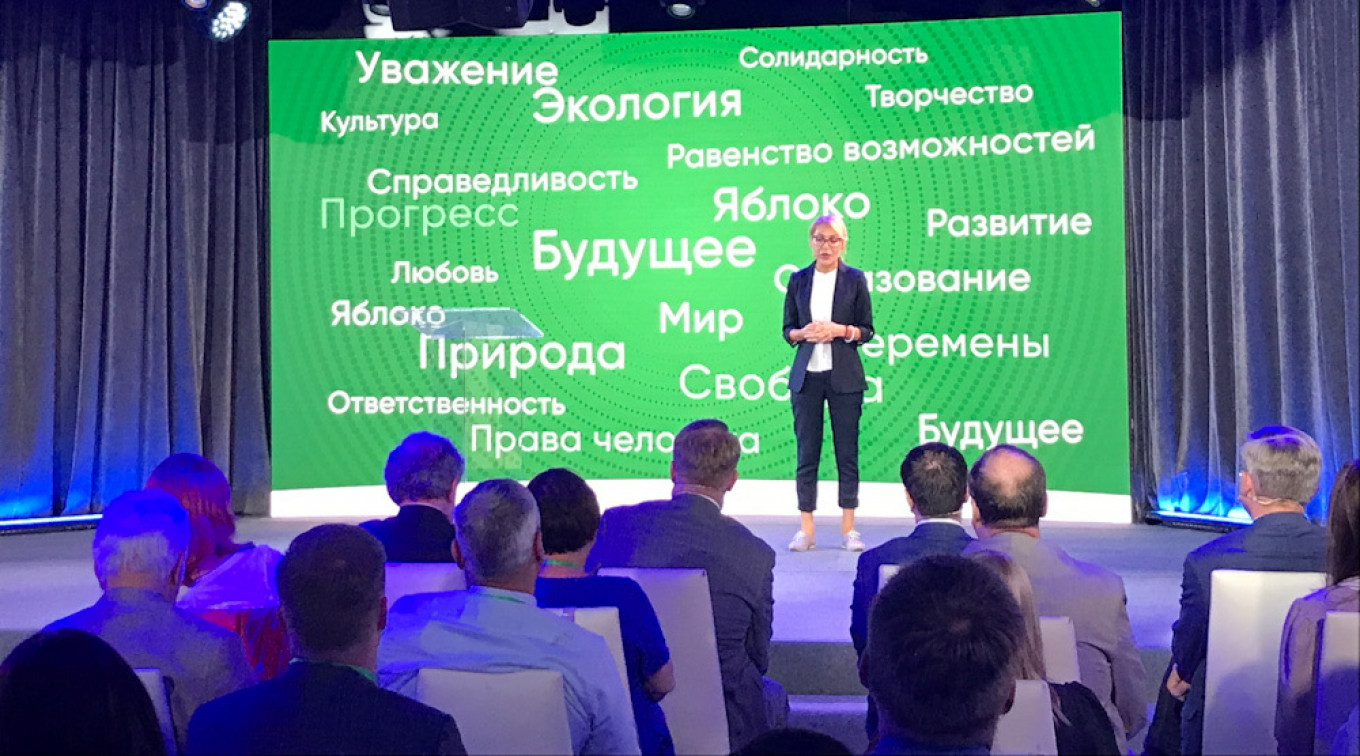

It’s an overcast Sunday morning in July, and on the fortieth floor of a plush Moscow skyscraper Russia’s last liberal party is gathering for its annual congress.

Beside the stage, a string quartet is playing, but the Yabloko party delegates — some ageing and well-heeled, some younger and edgier — have one thing on their minds: September’s high-stakes elections to the State Duma, Russia’s national parliament.

“These elections will determine the course of Russia’s future for decades,” said Kirill Goncharov, the twenty-six-year-old deputy head of Yabloko’s Moscow branch, and candidate for an opposition-leaning district in the Russian capital.

For stalwarts of Yabloko, a perennial presence on Russia’s political scene, the elections are a chance for the country’s long-marginalised liberals to convert discontent with an unpopular ruling party into a return to the Duma.

But with the Kremlin’s net widening, amid a crackdown on political opposition of all stripes, few are under any illusions about their prospects of victory at the polls.

“This could be the very last chance we have,” said Goncharov. “At any moment, they could decide to shut us down.”

It’s been a long time since Yabloko — which means apple in Russian — was anywhere near center stage in the country’s politics.

Founded in 1993 and an influential political player in the Yeltsin years, the party was virtually wiped out in the 2003 Duma elections, as its middle-class, urban electorate rewarded Russian President Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party for a booming economy and political stability.

These days, Yabloko rarely registers in national polling. In the 2018 presidential election, party founder Grigory Yavlinsky’s candidacy attracted only one percent of the national vote.

Despite its two-decade dry spell, Yabloko retains one key advantage: its legal status.

It’s very difficult to register a new political party in Russia without the Kremlin’s say-so, and would-be opposition outfits are regularly denied legal recognition.

Likewise, the bar for running without party backing is extremely high. Aspiring independent candidates must gather thousands of signatures and are often disqualified on technicalities.

All of this means that Yabloko — the only officially registered party in Russia committed to liberal democracy — has enjoyed exaggerated importance as one of the last routes into politics for otherwise marginalized Kremlin critics.

Occasionally, this has translated into protest votes for the party, with Yabloko converting anti-Kremlin sentiment into strong results in Moscow local elections in 2017 and 2019.

This has seen the party become the first port of call for opposition activists who are not party members, but who are otherwise excluded from Russia’s carefully choreographed electoral politics.

“I decided to run for Yabloko because there’s no way I’d be allowed to run as an independent,” said Alyona Popova, a prominent feminist, anti-domestic violence campaigner standing as the Yabloko candidate for a north Moscow Duma district in September.

“The authorities would absolutely not have let me gather the signatures.”

One opposition figure strictly off-limits to Yabloko, however, is Alexei Navalny.

The jailed Kremlin critic has a long and complicated relationship with the party in which he made his political start in the late 1990s.

Expelled from Yabloko in 2007 for attending an ultranationalist, anti-immigration demonstration and agitating against the party’s founder and informal leader Grigory Yavlinsky, Navalny won the lasting enmity of his former colleagues.

Earlier this year, amid large-scale demonstrations against Navalny’s imprisonment, Yavlinsky wrote an open letter denouncing the jailed opposition leader as a “populist” and warning supporters against protesting in his support.

In return, the more radical opposition centered on Navalny has traditionally seen Yabloko as a compromised, Kremlin-loyal party, similar to the nominally independent but Putin-aligned Communist and Liberal Democratic parties represented in the Duma.

With Navalny’s organizations now banned as “extremist” and harsh legal penalties for anyone cooperating with them, tensions between the two camps have risen in the lead-up to the fall parliamentary election.

After Yabloko refused to nominate a series of former organizers of Navalny’s now-shuttered regional headquarters as candidates for the September polls, Navalny allies took to Twitter to denounce the party as a Kremlin front.

“A party whose leaders are cowards and traitors,” exiled Navalny aide Ruslan Shaveddinov wrote of Yabloko.

“Shame on them.”

But for Yabloko’s faithful, excessive proximity to Navalny is a bridge too far for a party that has always had to chart a perilous course between oppositional values and the authorities’ demands for ideological soundness.

Last month Dmitry Gudkov, a former Duma deputy turned opposition figure, fled Russia. Gudkov, who had been running for the Russian parliament on a Yabloko ticket, said he had been told he would be jailed if he remained in Russia.

“We already know we’ve crossed some of the Kremlin’s red lines,” said Moscow party deputy head Goncharov.

“There are limits to what is possible.”

For many Yabloko members, the Navalny problem strikes at the heart of the party’s identity as a “systemic” political player, dedicated to achieving whatever change remains possible within Russia’s authoritarian, Putin-dominated — but still theoretically democratic — political arena.

It’s an identity that stands in contrast to the “non-systemic” Navalny movement, which rejects the existing regime as illegitimate, and demands its overthrow.

“We are not revolutionaries,” said Lev Schlossberg, a regional deputy in the western city of Pskov known as relative pro-Navalny radical within Yabloko.

“Russia still has elections and a constitution, albeit a defiled one, and we can still use them to change the country.”

For Schlossberg, Russia’s elections — which critics see as increasingly unfair — are no barrier to Yabloko’s mission to bring democracy to the country via the ballot box.

“Our job is to get so many votes that they can’t rob us of victory,” he said.

But for many Yabloko candidates, the outlook for the party is less optimistic.

With the Kremlin’s crackdown on all opposition escalating as the ruling party’s polling sinks to historic lows, many doubt that even the tame, “systemic” opposition will be allowed to participate in a political arena increasingly closed to critics of the official line.

“It’s very possible that the Kremlin will stop me from running in the end. But you can’t not participate,” said feminist activist Alyona Popova.

“Otherwise people would lose hope.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.