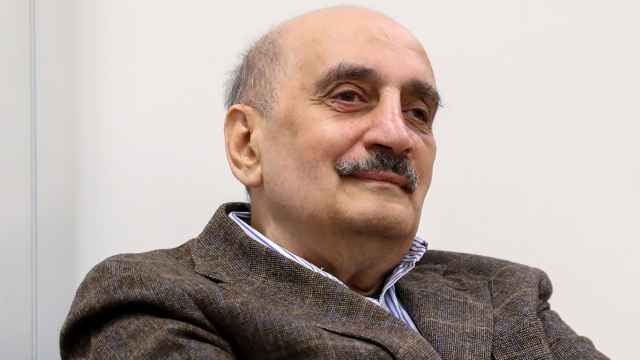

Pavel Chikov has had a hectic year.

As the Russian authorities’ crackdown on dissent has widened, so has the workload of one of the country’s leading human rights lawyers.

“It’s been a busy few days...months,” Chikov said in an interview in a central Moscow cafe this week.

Chikov, 41, is the head of Agora, a countrywide association set up in 2005 by human rights lawyers. As an umbrella organization, Agora oversees a number of smaller legal aid groups specializing in issues from political protests to prison torture.

All together, Chikov estimated, he leads a team of over 200 lawyers that take on some of the country’s most challenging human rights cases.

“In almost all the big cases you read, our team is somehow involved,” he said.

Members of the team represent the hundreds of Alexei Navalny supporters charged for attending unsanctioned meetings this January in support of the jailed Kremlin critic. Clients also include the messaging app Telegram and Russian Twitter users who have taken on the authorities in landmark lawsuits surrounding internet freedom.

Born and raised in Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan, Chikov graduated from the Law Department of Kazan State University and earned a degree in public administration from the University of North Dakota in 2001.

Shortly after coming back, he became active in Russia’s human rights community after noticing it lacked professional lawyers, he said.

“There were legendary veteran Soviet human rights defenders like Yuri Orlov, many of whom had a science background. And you had the clever managers who knew how to attract funds for different causes. But not many who knew how to practise law,” Chikov said.

In 2003 Chikov became the head of the legal department of Public Verdict Foundation, one of the largest Russian NGOs in the field of legal protection of human rights. In April 2005, he founded the Interregional Association of Human Rights Organizations, known as Agora in a nod to the ancient Greek tradition of discourse in public meeting spaces.

Chikov said much has changed in the way Russian law enforcement works since he first started out.

“Cases that we won back in the day seem absolutely impossible now. Sometimes it feels like we live in a different country.”

In 2011, for instance, Chikov’s team secured the acquittal of a group of anti-fascists and ecologists who attacked the local municipal offices in Khimki, a city on the outskirts of Moscow.

“I can’t imagine that verdict would ever happen today,” Chikov said.

Despite recent crackdowns on dissent in Russia, however, Chikov remains upbeat.

The danger, he said, is that lawyers might stop trying to understand the authorities.

“From the outside, it looks like Russia’s judicial system is one big brutal machine. But it’s so much more complex than that once you dig in,” he said.

With a fork that was lying next to him, Chikov drew out an imagined pyramid of Russia’s legal system.

“At the top, the most complicated and sensitive issues are those linked to state treason, that is where you have to deal with the Federal Security Service or FSB.”

When defending clients in those cases, Chikov said, his lawyers faced “a steep uphill battle.”

This he said was followed by topics like “defending” terrorism and being charged with receiving foreign funds.

“But after that, things get a little better,” he said, smiling.

He said when dealing with topics like domestic violence and prison torture his clients had a better chance of convincing the prosecution of their pleas.

However, this “pyramid” Chikov said, is constantly evolving and shifting

He pointed out how in the months following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its involvement in eastern Ukraine, authorities were very sensitive to cases that involved Ukraine, while recently cases linked to LGBT issues are being prosecuted more harshly.

“That is why I am always checking the news, looking for little signals that can tell me what chances our clients have. Deciding what our strategy will be,” he said.

While authorities have increased the numbers of prosecutions of opposition politicians and activists over the last few years, the lawyers who defend them were believed to be off-limits.

This changed in April when Ivan Pavlov, a close acquaintance of Chikov and one of Russia’s leading defense lawyers, was detained on criminal charges of disclosing details of an investigation hours before he was due in court to represent former journalist Ivan Safronov, who is accused of treason.

Chikov believes Pavlov’s arrest can be traced back to his “sensitive” work defending Safronov.

He also said that by leading Agora while not directly representing clients in courtrooms, he has built a safety buffer for himself.

“But of course, they could come for any of us tomorrow,” he added.

Russia’s Justice System is notorious for being skewed against the accused.

According to 2018 statistics published by the Supreme Court’s Justice Department, Russian courts heard criminal cases against 497,141 people in the first six months of 2018, and acquitted just 1,044 suspects, or 0.21%. Human rights critics say these numbers show courts tend to accept whatever prosecutors argue.

In comparison, the acquittal rate from 2017 to 2018 in U.K. magistrates courts was approximately 15%, according to British Criminal Justice statistics..

“This doesn’t mean our work is hopeless from the start,” Chikov said.

“What we do will decide the length of a sentence, even when it’s a guilty verdict.”

Chikov said Agora works hard behind the scenes to prevent the prosecution from opening cases in the first place and has learned that public attention is not always beneficial and cases can be decided behind closed doors.

“It is commonly assumed that making a big fuss will help and sometimes it’s definitely true,” he said.

But the system is complicated and sometimes shouting loudest will work against you”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.