This summer a small private museum in the center of Moscow is having a big party. The Anatoly Zverev Museum (AZ Museum) is celebrating its third anniversary with an exhibition of works by Zverev of every genre and every period of his artistic career. Polina Lobachevskaya, museum curator, said, “We didn’t have a complex concept of the show. We simply organized a party — all of Zverev’s genres and as much as we could fit into the space.”

Artist and his times

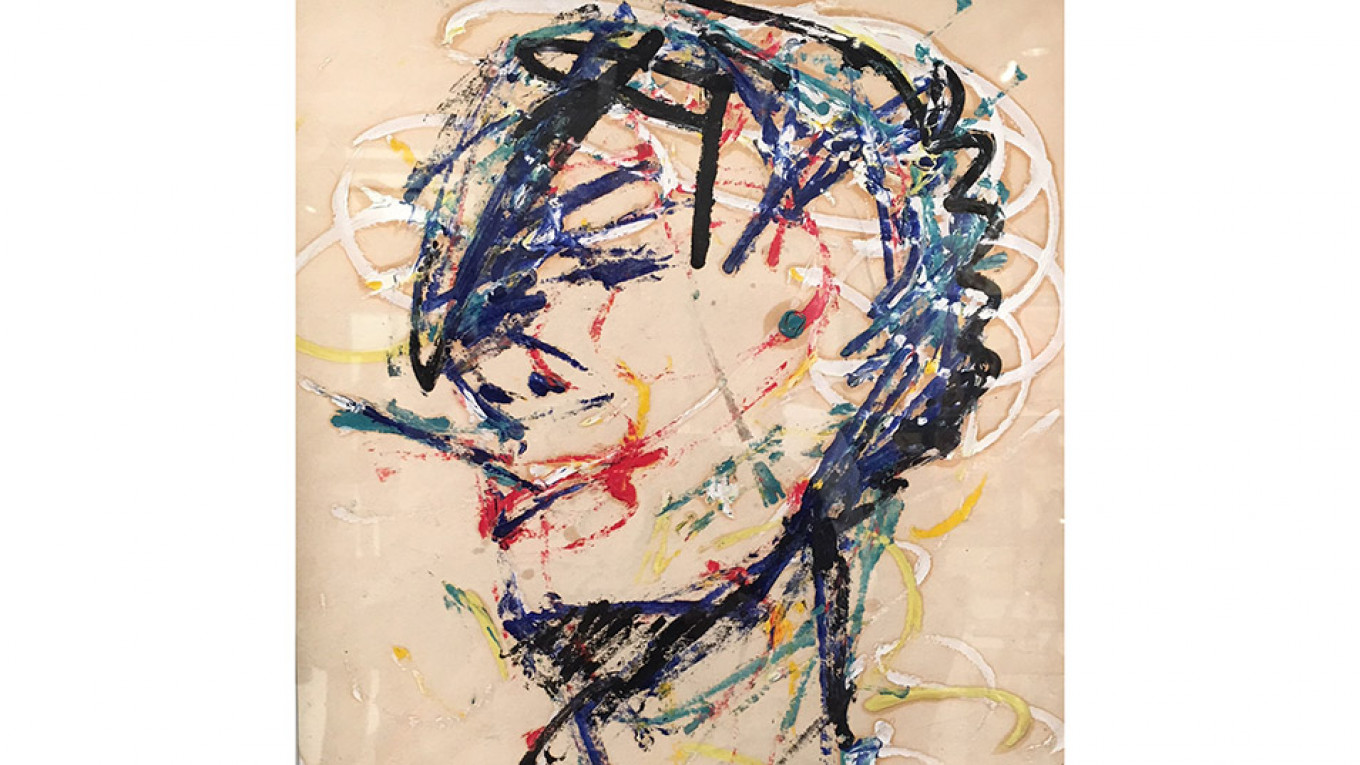

Anatoly Zverev (1931-1986) was one of the most famous of the “non-conformist” artists of the post-war period in the Soviet Union. And he was certainly one of the most prolific, with an estimated 30,000 works attributed to him. He did not have a formal art education, was not part of a group or movement, and worked in many genres: painting, drawing, illustrations and graphic art. He also wrote poetry, philosophy and treatises on board games. He changed and matured over time, changing his style without imitating any other artist and without losing anything of that “I” that made his works instantly recognizable, whatever the medium, subject or year created. French playwright Jean Cocteau said he was “the only artist who worked all the way through Western painting, from early Picasso to the present day.”

Being a “non-conformist artist” in that period meant creating work that did not conform to the dictates of socialist realism. That entailed not being admitted to the Union of Artists; not having access to materials — domestic or imported canvas, paints, brushes, paper sold only to artists in the Union; not being able to exhibit or even legally sell one’s work; and being subject to arrest for “parasitism” since creating art outside the Union was not recognized as a profession. Zverev’s works are often done or poor quality paper and scraps, cardboard, wood or any other more or less applicable surface.

With the exception of a small show in the exhibition space of the Moscow City Committee for Graphic Artists in 1984, Zverev was not exhibited in his homeland during his lifetime. His first major show abroad was in Paris in 1965. His first solo show in Russia was 34 years later in 1999 at the Treyakov Gallery.

The AZ Museum was founded with a mission to collect and preserve Zverev’s works and to showcase, study and acquaint the public with the extraordinary flourishing of art in the second half of the 20th century in the Soviet Union — so rich and talented that Lobachevskaya calls it the “Soviet Renaissance.”

Gala of art

The AZ Museum does not display a permanent exhibition. Every three or four months it closes the premises and redesigns the entire three floors to create the proper setting for the works in the next show. “Setting” is not just the placement of temporary exhibition walls. The museum is transformed with newly painted walls; specially designed cases, backdrops and frames; special lighting that often changes several times an hour to change perception of the works; films played over walls; unique films and animation; and music and sounds played in the background.

This show is no exception. The 250 works on display — about a fifth of the museum’s collection of works by Zverev — include portraits, landscapes, drawings, doodles, illustrations and an animated film based on the illustrations by Mikhail Aldashin.

That’s a lot of works in a small space, but the design and lighting by Anatoly Golyshev keep it from being overwhelming. Walls of bold color, spaces of light and darkness and sets of paintings and drawings in screens like iconostases let you contemplate groups of works apart from the rest. In the background, music from the 1960s is played in a loop, adding subliminally to the upbeat mood of the show.

'The greatest Russian draftsman'

The first floor of the show is dedicated to Zverev’s portraits and self-portraits. Over the years, he asked dozens of women to pose for him with the line: “Sit down, kiddo and let me make you immortal.” And so he did. His portraits of his women friends young and old are among his most famous and beloved works. He was also a constant chronicler of himself, producing hundreds of self-portraits in drawings and paintings.

The second floor has even more portraits of women, as well as drawings and sketches of faces and nudes. You see why Pablo Picasso, who saw his works in Paris in 1965 show, reportedly called him “the best draftsman in Russia.” Here, too, are landscapes of churches, pine forests and rivers, painted with the same emotion as his portraits to create complex images of beauty, decay and suffering.

The third floor exhibits some of Zverev’s early “supremacist” drawings and paintings from the 1950s, where the abstract and geometrical themes of the early 20th century Russian avant-garde are textured and richly colored. From the same period (1955) are the illustration’s for Gogol’s “Diary of a Madman” from the collection of Dmitris Apadidis, exhibited for the first time, and the charming film by Aldashin.

At the end of the exhibition you leave with an appreciation for the extraordinary talent and scope of Anatoly Zverev. But perhaps more importantly, you leave with a sense of enormous pleasure in life and joy. And that is Zverev’s greatest gift.

AZ Museum. 20-22 2nd Tverskaya-Yamskaya Ulitsa. Metro Mayakovskaya. www.museum-az.com. Until Jan. 20, 2019

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.