The call to prayer ushers worshipers to gather for the imam’s sermon.

The main hall for men is tightly packed. A couple of dozen more spill out into the corridor. In a separate hall, three elderly Muslim women sit on benches, listening through a monitor.

The imam is preaching tolerance, love for one’s neighbor and Islam as a religion of peace that calls on Muslims and non-Muslims to live in friendship and harmony.

Twelve years ago, Kifakh Bata Mohammed gave up his tourism business to become an imam at the mosque in Volzhsky, a city in Russia’s southern Volgograd region. Originally from Syria, he founded what would become Russia’s largest Islamic center outside a predominantly Muslim region. More than 60 students attend courses at the center on a regular basis.

“The main thing now is to protect our youth from the influence of extremists who masquerade as devout Muslims and trick them into joining Islamic State*," Kifakh Bata said. "This is especially true in southern Russia.”

“A lot depends on how educated our theologians, or imams are,” he said.

The Dark Side

The Volgograd region is home to around 30 mosques, all of which run extremism prevention programs. But there are still cases of Muslims switching to the “dark side.”

In 2017, Russian President Vladimir Putin said there were around 9,000 people from Russia and former Soviet republics fighting in Syria.

Volgograd was also the site of twin suicide bombings in December 2014, just before the Sochi Olympic Games, that killed 34 people. The bombers were identified as coming from Dagestan in the North Caucasus, where Russian authorities are struggling to contain an Islamist insurgency.

Among the shelves lined with Arabic texts and Quran quotations in the imam’s office hang plans for a new mosque. It is snow-white and round with arched vaults. The building could become the main attraction of the small city, but residents have resisted the project.

Opening the Islamic center in Volzhsky was also difficult. On two occasions city officials took back land from the Union of Muslims they had earlier allocated for the center.

So when city authorities offered Kifakh Bata dilapidated barracks on Green Island, on the outskirts of town, the imam gladly accepted. Built as temporary accommodation for Soviet workers, the barracks had for decades been without running water or central heating. But anything was better than a basement.

Undesirables

“When we came here, I said that within one month, which was the first Friday of Ramadan, I would give my first sermon here,” Kifakh Bata said. “Nobody believed me. But everyone – congregants, students, employees of the center and activists – gave it their best effort.”

“We remodeled the main room and patched the roof. And on the first Friday of Ramadan, we held the first namaz,” he said, using the Arabic for prayer.

Volzhsky has a population of more than 300,000. Approximately 50,000 make up the city’s “ummah,” or Muslim community. That community numbers 200,000-250,000 over the entire region, around one-tenth of the general population.

“It is unfair that so many people cannot pray in dignified conditions,” Kifakh Bata said.

By contrast, not a single Orthodox church stood in the region in the 1990s, but four large churches have been built since – and that is not counting those in small parishes. There is even a men’s monastery that also stands on Green Island.

“I think it is this attitude towards Islam, and not only in our country, that prompts some Muslims to leave for Syria and fight on the side of the self-proclaimed Caliphate,” said Kifakh Bata.

A circuitous route

Kifakh Bata moved from Syria to Russia in 1987.

Under a state-sponsored program, he entered the Volgograd Polytechnic University and earned an engineering degree. After graduating, he decided not to return to his native Latakia on the Mediterranean, where his parents and six siblings live.

Instead, he started a business in Volgograd helping Syrian students get into local universities. He opened several cafés and a travel agency. In the early 2000s, he went to Egypt where he arranged excursions for Russian tourists.

Kifakh Bata admits that he wanted to settle in Egypt, but his wife was so homesick that they had to return to Russia. What’s more, by that time he already had theological duties in Volzhsky.

Kifakh Bata is a descendant of the Prophet. For non-Muslims, it can be difficult to understand the status such people hold in the Islamic world. It would be the same if Jesus had children, and their descendants lived among us today.

As a businessman, Kifakh Bata became a leading figure in the Volgograd Region Union of Muslims. When the Volzhsky imam passed away, Kifakh Bata was invited to replace him.

At first, he tried working both jobs. But he soon realized it was impossible to preach on a Monday and balance his accounts on Tuesday. He closed his travel agency and devoted himself entirely to theology, which he says was his true calling.

The madrasa operates as a branch of the Dagestan Islamic University, where the most highly-regarded Muslim theologians teach. The university sends instructors to the Volzhsky center and receives that school’s instructors as interns.

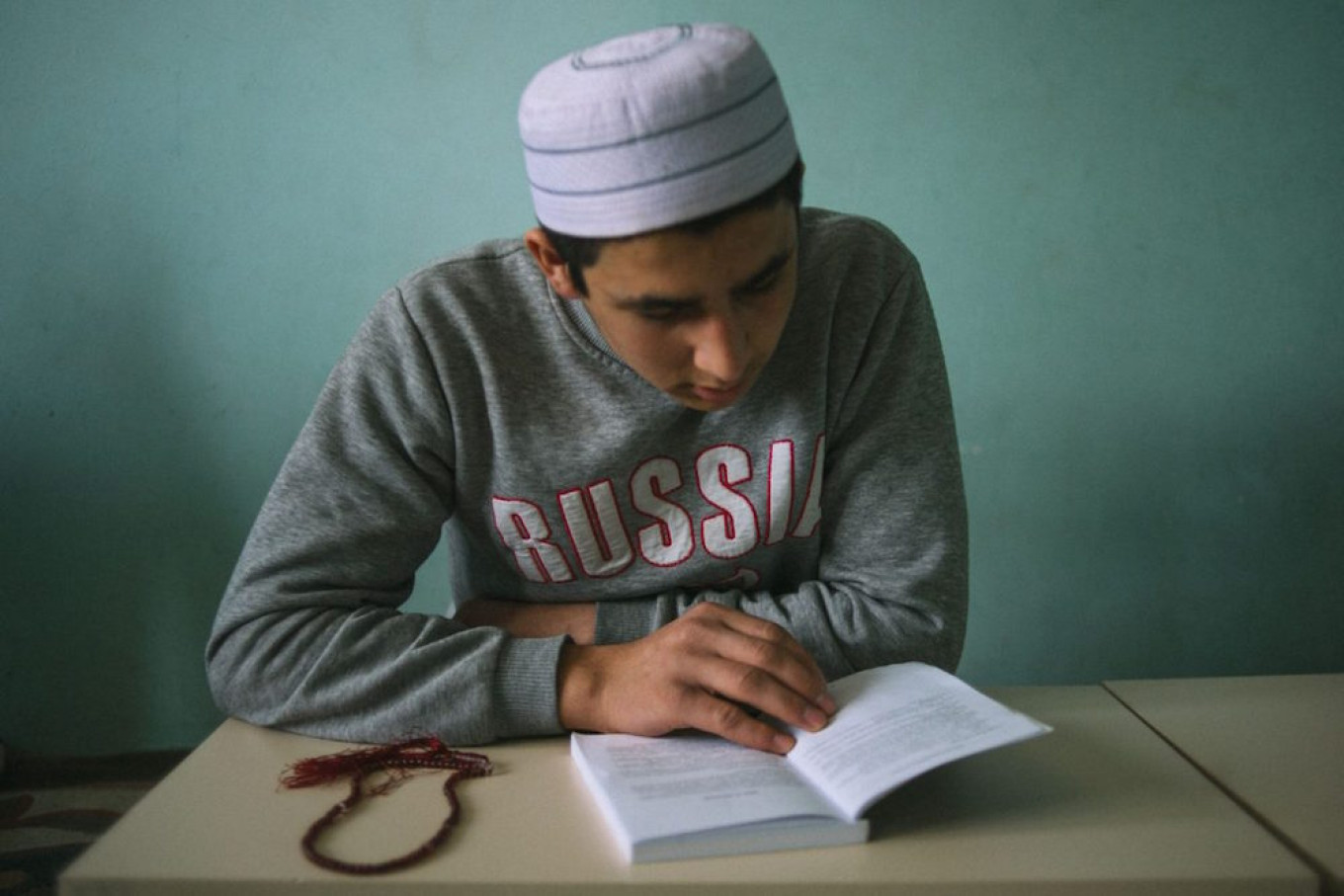

More than 60 students of all ages study at the center. Classes begin early in the morning when everyone gathers in the main hall and sits on the floor behind desks covered with notebooks and books in Arabic. The newest students sit in the first rows and those with more experience farther back.

The basics

One of the first-year students is 32-year-old Abdullah, who went by Alexander until his conversion to Islam. A native of the small village of Uspenskoye in the Astrakhan region, he works at his notebook, meticulously copying ornamental Arabic script.

“In the first year we study the basics of Islam and I am learning to read Arabic,” Abdullah said.

“In the mornings, we run and work out. We also help maintain the grounds, but our main task is to study. The students don’t have to worry about clothes and food. The Lord provides and we help out,” he said.

Abdullah never belonged to any religion, but always believed in God. He came to Islam when someone close to him died and praying helped ease the pain.

“After that, I woke up, washed, and told the Lord that now I was His,” Abdullah said. “The same day, I gave up drinking and smoking and came to the mosque.”

“In Islam, I found answers to what had burdened and troubled me for many years,” he said.

“Islam does not spread through bloodshed,” Kifakh Bata says. “It attracts followers through its emphasis on morality.” He explained that in Islam there are two types of jihad. The greater jihad is the struggle against one’s own vices. The lesser is the holy war for one’s home.

The main theme running through the imam’s sermons, meetings, and personal conversations – at the center, in small villages, or with prison inmates – is the danger of terrorism and extremism.

Kifakh Bata believes he is fighting a struggle for the soul of every single Muslim, helping them to choose life and peace.

“Many theologians and scholars, including several of my friends, were killed for trying to spread these teachings,” Kifakh Bata says.

Youths trying to find their place in life often go to the Internet to find answers, where they fall victim to Islamic radicals. “Terrorists use the lesser jihad exclusively for their own purposes – to seize power and wealth,” said Kifakh Bata. He believes that young people who are searching should go to the mosque to find answers.

“There is a great need for properly prepared theologians,” Kifakh Bata said. “After all, the moral condition of congregants depends on them. It is no easy burden to be responsible for other people’s souls.”

"It is no easy burden to be responsible for other people’s souls.”

A young man who planned to go to Syria once approached the imam. Because Kifakh Bata hears stories from his relatives there, it was easy for him to dispel the young man’s “romantic” notions.

He also explained that a Muslim preparing for jihad must first fulfill special conditions: he must obtain the blessing of his imam and parents.

“During the Great Patriotic War, Muslims declared jihad,” Kifakh Bata explains. “They defended their home and country from the enemy.”

“Who was that young man going to defend in Syria – terrorists who ravage and kill local residents, who carry out attacks in cities around the world?”

Kifakh Bata convinced the young man not to go. But how many never stop to ask for advice?

This article was first published by Takie Dela.

*Islamic State is a terrorist organization banned in Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.