The setting of Dmitry Sukhanov’s pre-season bootcamp is distinctly medieval. The corporate retreat outside Moscow is designed to look like a Germanic castle. But beyond the hotel’s walls, a very modern scene is playing out.

In a dimly lit hotel room, a pack of 20-year-olds in sweatsuits stare into computer screens lining the wall. Their fingers click hundreds of times per minute. Between scattered furniture and rows of empty water bottles and soda is a whiteboard covered with a crude map, arrows and motivational buzzwords you might find in a football locker room.

But this isn’t a football training camp. The team, known as Virtus.Pro, is one of Russia’s premier professional video game teams. They are in the middle of a grueling training week in preparation for the country’s most prestigious video game tournaments. The prize: a 2-million-ruble-payout and a shot at a world championship.

The rise to the top of Russian gaming began last summer for Sukhanov’s team. During the annual regional League of Legends championship, Virtus.Pro inched ahead of the previously dominant M-19, and claimed the championship’s 1.5 million ruble prize ($26,300). “M-19 was the best team until last year, when we beat them. Now I think we are one of the top teams.”

The stakes are higher this year, Sukhanov says. “The League of Legends Championship is a bit like a football tournament. Starting June 24, we will play three games a week for five weeks,” the coach says. “The winner of this tournament will go on to an international playoff, and the winner of that playoff will have a shot at a world championship.

"Virtus Pro is one of Russia’s premier professional video game teams"

Pro-Gaming at a Glance

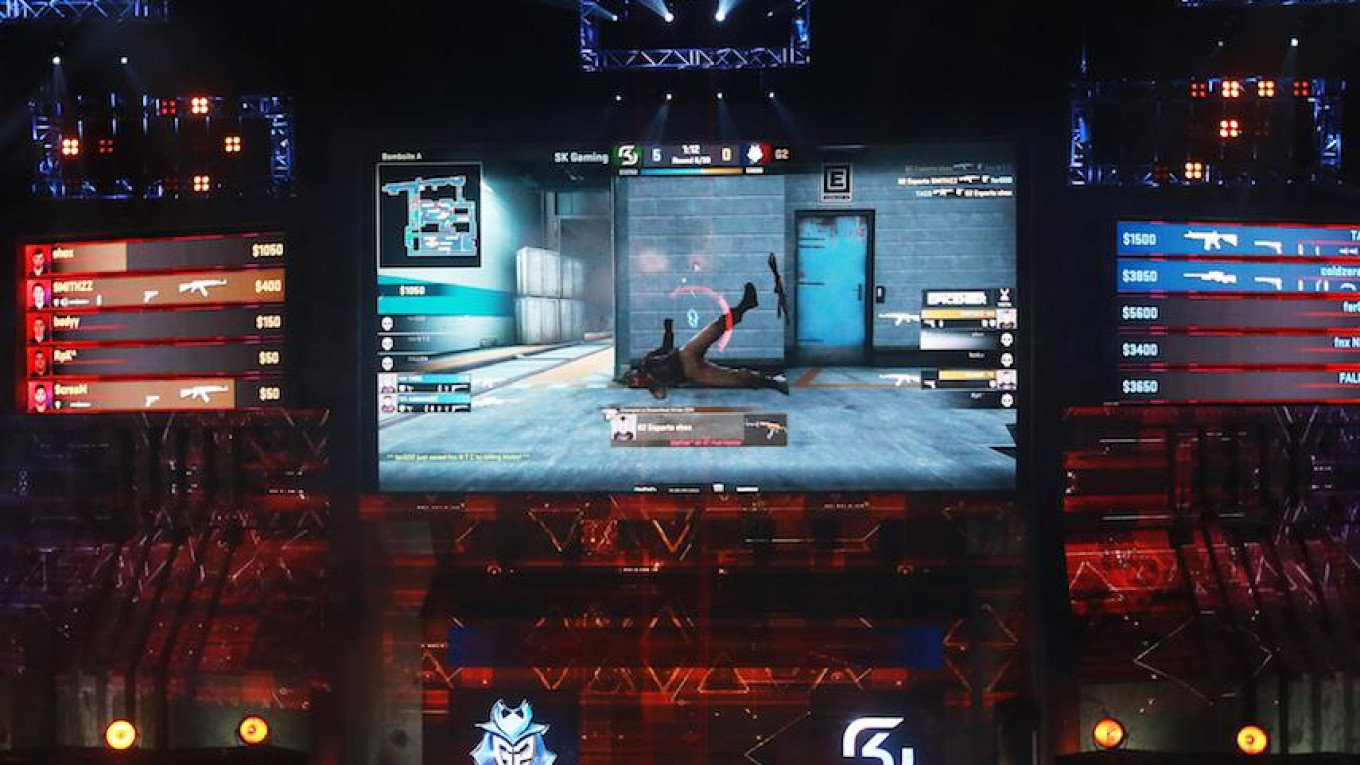

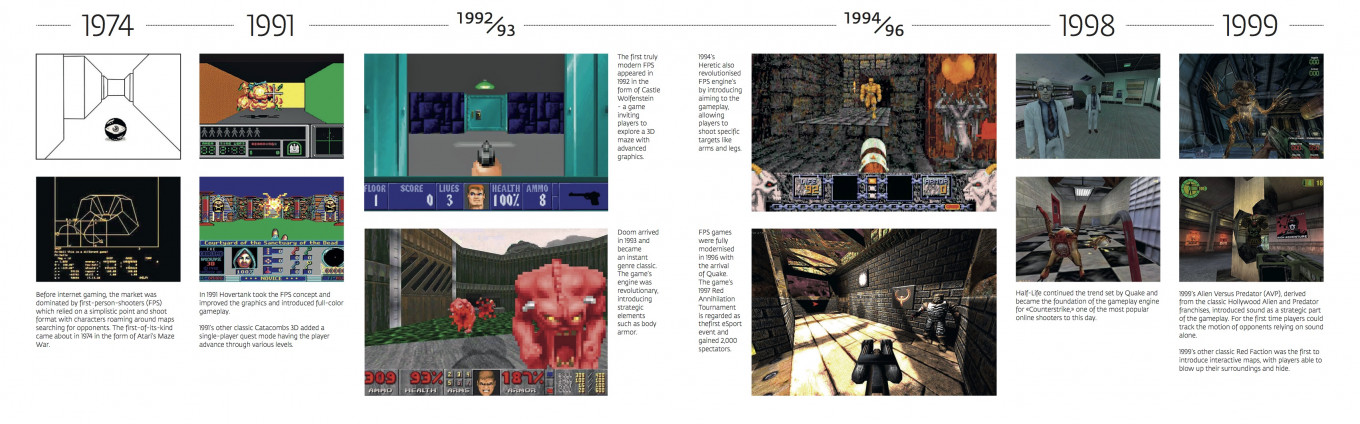

Once a niche market for hardcore fans, eSports has hit the global mainstream. The sport sees teams from across the globe take part by playing competitive matches of popular online games in high-stakes tournaments. Some, such as League of Legends and Defence of the Ancients 2 (DOTA 2), rely heavily on tactics and strategy. Others, such as Counter-Strike and Starcraft, hinge on lightning reflexes.

With more people than ever before gaming in their spare time, the global eSport market is expected to pull in $1.1 billion by the end of this year. Traditional sports franchises are taking notice.

In 2016, NBA franchise the Philadelphia 76ers purchased two eSport teams: Team Dignitas and Team Apex. Axiomatic, which owns teams like the L.A. Dodgers baseball team and the Washington Wizards basketball team purchased a majority share in Team Liquid, a global eSports brand based in the Netherlands. Soccer teams Paris Saint-Germain, Manchester City, Ajax, and Schalke FC have all announced that they’re set to create their own eSports division.

Global eSport audiences are growing too. Upwards of 385 million viewers are expected to tune in on cable or online to watch cyber-sport tournaments in 2017. The most popular games usually give fans a third-person or birdseye view of the action.

“Competitive cybersport has this great potential to draw in a diverse audience due to its dynamism,” Dmitry Smit, the president of the Russian eSports Federation (RESF), told The Moscow Times. “National computer sport federations, the cybersport industry, and the media are all working on new formats which will bring e-sport to a mass audience."

Russia’s Gaming Landscape

Russia has proven to be one of Europe’s most fertile cybersport markets, topped only by Sweden. The Russian Ministry of Sport officially recognized gaming as a sport in 2016, making top cyber-athletes eligible for state sporting awards.

Tournaments are already filling Moscow’s largest stadiums, with fans paying out as much as 9,900 rubles ($175) for three-day passes. These events draw Russia’s professional teams, each backed by major Russian sponsors.

Dmitry Belyaev, a 27-year-old corporate lawyer, jumped in on the action in 2007 when he founded Elements Pro Gaming—today a mainstay of the Russian professional gaming scene.

Belyaev says that Russia’s love of pro-gaming is akin to the nation’s love of chess. “Chess is very similar to eSport disciplines such as DOTA 2 and League of Legends,” he says. “Players have to build their teams by combining different video game characters with different strengths and weaknesses.”

Just like chess grandmasters, Belyaev expects his cyber athletes to show real dedication to their craft. “In any sport, if you want to achieve high results, then you need to train forward and compete in professional tournaments,” he says.

To help foster high performance from their cyber athletes, teams try their cyber athletes, teams try to provide all the trappings of a professional sports team. Instead of football stadiums, teams like Elements Pro and Virtus.Pro use bootcamps and “game-houses,” where their team comes together to practice and play.

Sukhanov, head coach for the Vitrus.Pro League of Legends team, keeps his players on a tight training schedule. Lunch is served at 2 p.m., followed by a light warm-up. Training begins two hours later and can last until 2 a.m.

Sukhanov, who previously worked as a chemist, says that an analytical mindset helps him coach the very best from his players. “We play together, but we also watch replays of individual matches and analyze them,” he says. “We make sure that every team member understands our tactics.”

As well as high-end equipment and individual coaching sessions, teams often work with therapists in a bid to help their players reach their peak.

The psychologists are there to help cyber athletes cope with stress, Belyaev says, which can be intense. “Cybersport is always changing.” Sometimes, you will prepare intensely for a tournament, and the game’s developers will release an update in the middle of a competition that changes the way the game is played. “Teams will have to change their tactics overnight.”

If cyber sports teams take their games as seriously as classic athletes, so do their fans. One of the biggest markets surrounding cybersports is betting. In 2016, revenue from e-sports wagers hit $60 million, and those playing the books will sometimes try to tip things in their favor.

While training for a recent competition, one Virtus.Pro’s team was hit by hackers, robbing players of valuable training time. At this in Moscow bootcamp, Virtus.Pro are only using secure connections and avoiding vulnerable programs like Skype.

According to Element Pro’s Belyaev, hacking efforts are common before competition. “That’s why we are building good security into our network at our new game house,” Belyaev says.

Russia vs The World

Yet although Russians have a reputation for being hardcore gamers, they have yet to carve out a spot for themselves alongside cybersport powerhouses such as China and South Korea.

Belyaev says that Russia’s young cyber athletes lack a clear career template. “Talented players are left to their own devices, training without any kind of system in place,” he says. “They are either forced to seek out a team on their own, or doomed to play with less talented friends.”

Parents and teachers also try to stop talented children from playing “harmful” computer games, or judge cyber sport as a “useless occupation,” says Belyaev.

Dmitry Smit from RCSF agrees these attitudes hurts e- sport’s development. “Attitudes change when cyber-athletes start to earn money,” he says. “The most common question that cyber athletes are asked is, “what do your parents think of what you do?”

The answer is usually somewhere along the lines of: “At first they didn’t understand, but when I began to earn money, they started to support me.” The support of friends and relatives comes first, and then, very gradually, support across society starts to form.“

Teams also face more practical problems. While some rookie players are scouted at regional tournaments or online, teams such as Virtus.Pro often bring in players from abroad to bolster their ranks.

But some Russian teams say that they are struggling to properly recruit foreign talent because they lack any legal mechanisms to bring them here to play full time.

Russian players traveling abroad can also face difficulties. “Those who play regularly at tournaments often lose great chances to perform due to visa problems,” Belyaev says.

A Russian Tiger

At bootcamp outside Moscow however, Virtus.Pro’s League of Legends stars are confident in the future of Russian cybersport. Twenty-one-year-old Ivan Tipuhov captains the team. He’s sure that given more time, Russia is more than capable of rivaling South-East Asia’s eSport prowess.

“Cybersport is already bigger than sports like hockey,” he says. “In five years, eSport could be bigger than basketball. Ten years and it could be bigger than football.”

To hone their skills, Ivan and his teammates often scrimmage on European servers — rather than Russian ones — where the standard of competition is higher. Through this type of informal international competition, Sukhanov is certain that Russian cybersport athletes will soon reach the very top of their craft.

“We need to see players improve their individual skills [in order to compete],” he says. Chinese and South Korean players have these skills because they are incredibly dedicated to eSport — they practice and attend bootcamps all year, even during the offseason. “But Russian players also have this drive,” Sukhanov says, “they can compete on this level.” TMT

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.