Tatyana’s (not her real name) stepfather started small.

At first, he’d get annoyed by things she did. He criticized and he lectured her. Later, the lectures would stop, and this is when the outrage began. And when the outrage stopped, the spanking and face-slaps started.

“He just went mad,” Tatyana says. “For five years, he beat me and my mother senseless.”

Tatyana’s story is far from unique. Every year, tens of thousands of Russian women and children suffer every possible kind of familial abuse — be it battery, rape, or even attempted murder. Years after escaping with her mother, Tatyana, now 29, says domestic violence must be tackled and punished before it gets out of control.

But not everyone agrees with her.

Ultraconservative Federation Council senator Yelena Mizulina, best known for her “gay propaganda” law, introduced a new bill to the State Duma on July 27 that proposed the decriminalization of battery within families. “Battery carried out toward family members should be an administrative offense,” Mizulina said. “You don’t want people to be imprisoned for two years and labeled a criminal for the rest of their lives for a slap.”

What Mizulina failed to acknowledge was that domestic violence in Russia is a serious problem, and not limited to parents spanking their children for misbehaving.

According to official Russian government statistics that undoubtedly under-report the situation, a massive 40 percent of all violent crimes are committed within the family. This correlates to 36,000 women being beaten by their partners every day and 26,000 children being assaulted by their parents every year.

Larisa Ponarina, deputy director of the Anna Center, an NGO helping victims of domestic violence, suggests that more than 14,000 women die every year as a result of domestic abuse.

She does not believe the situation is improving.

A Battle of Values

Mizulina’s bill comes on the heels of a recent amendment to the Criminal Code, introduced by the Supreme Court and signed into law by president Vladimir Putin. According to the amendment — one of the rare progressive legislative moves in fighting domestic violence — battery of family members was put on an equal footing with hooliganism and hate assaults as a criminal offense to be investigated and prosecuted by the state. It came into force in early July.

Traditional family values crusaders supported Mizulina’s attempts to undo the amendment. The Russian Orthodox Church issued a statement saying that “if reasonable and carried out with love, corporal punishment is an essential right given to parents by God.”

The All-Russian Parents’ Resistance, a movement fighting against the juvenile justice system, has warned that criminalization of familial battery will lead to prosecution of parents who were acting in their children’s best interests. “A mother spanked her son for watching porn ... but his teachers in school noticed bruises, complained, and the court made the mother pay a 8,000-ruble ($120) fine ... Parents no longer have the right to choose methods of up-bringing,” a statement on their website says.

“Traditional, or rather archaic values have become popular again,” says Alyona Popova, activist and women’s rights advocate. High-profile stories of abuse — movie stars beating their wives into a coma, female journalists posting pictures of bruised faces after fighting with their significant others— have done little to change the situation. Indeed, commentators — both male and female — have even intimated that the victims “most probably provoked” incidents, “were asking for it with frivolous behavior,” or “knew who they were marrying and should have known better.”

“Women aren’t supposed to be able to do and achieve things on their own,” says Popova. “Society tells women to get married in order to let their husbands decide things for them. If a man beats you, it is because he is stronger and has the right to beat you, and you should consider yourself lucky to be married in the first place.”

It Runs in the History

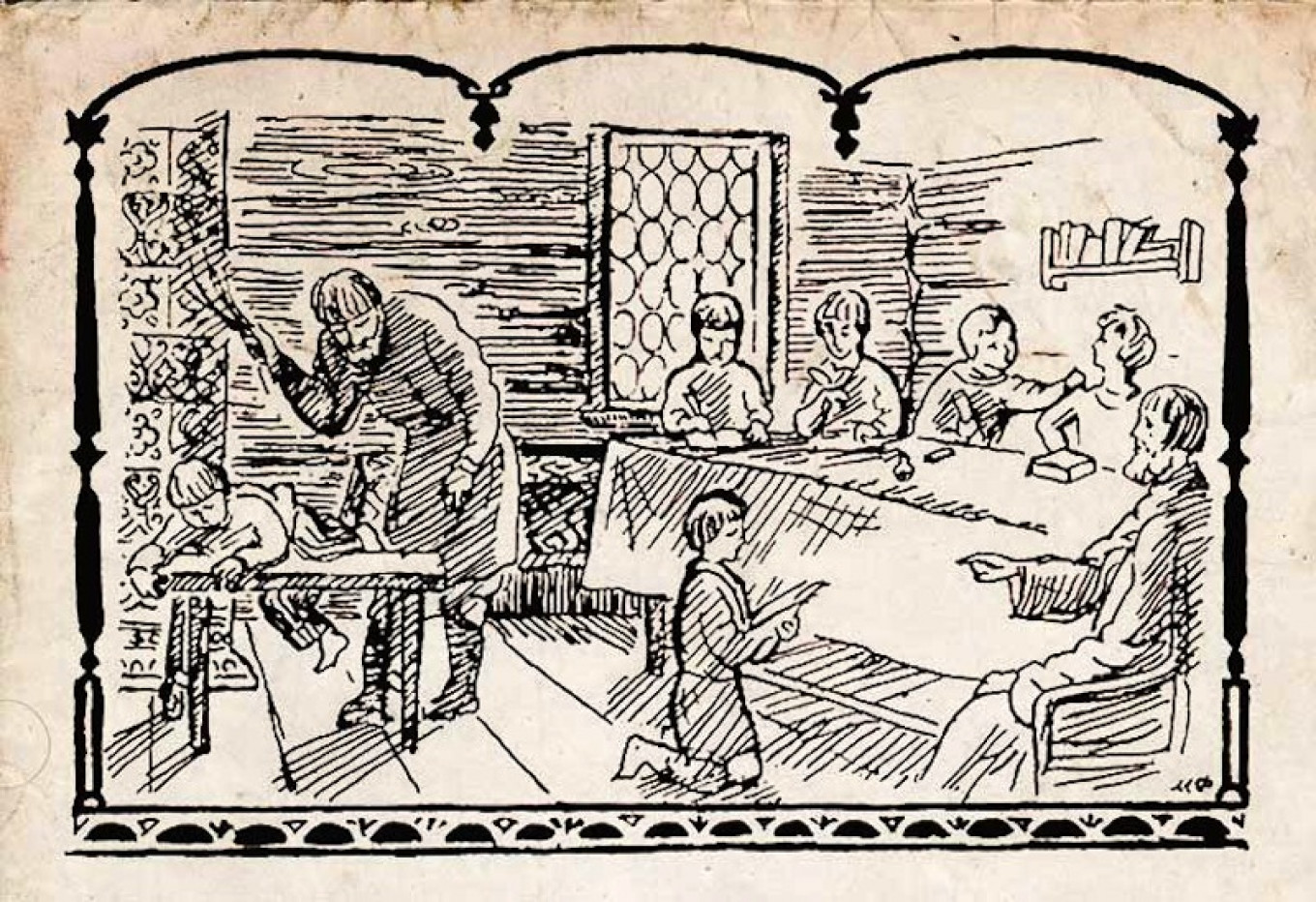

“If he beats you, it means he loves you,” as one famous Russian saying has it. According to some studies, the phrase first appeared in the late 16th century, after a book called “Domostroy” (“Household”) was published. This book, a guide for families, carried a strong Orthodox Christian message. It outlined women’s obedience as the key to a strong, lasting family, and described corporal punishment — for women and children — as a “mere blessing” that can help “avoid death of the soul.”

The Domostroy mentality was rejected for a short period in post-revolutionary Soviet Russia in favor of equality. But it made a triumphant return during later in the Soviet period, although without previous religious undertones, before embedding in the social norms of 21st century Russia. Today, police stations rarely take reports of familial battery seriously — they often dismiss victims’ complaints, citing the problem as one’s “internal family matter.” Some say that they can only intervene when a murder is committed.

Such abnegation of duty is hardly surprising, given the fact that the Russian government has never properly addressed the issue either. The UN, on the other hand, commissioned several worrying reports about the state of women’s rights in Russia in the past 10 years. Some of the earlier reports contained recommendations, such as adoption of specific legislation on domestic violence, establishment of shelters and other support for women victims of violence. Later, it became clear to the report writers that Russia had done little to implement the measures.

One of the few countries still to adopt a domestic violence law, Russia hasn’t signed or ratified the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence; this came into force exactly two years ago, in August 2014. All attempts to pass a domestic violence law in the past ten years have been unsuccessful. The most recent bill, drafted by human rights advocates and specialized NGOs, is now ready for the first reading.

But it has been sitting on a shelf in the State Duma for a year.

Baby Steps

Supporters of “traditional values” explain their lack of enthusiasm for a new domestic violence law in terms of protecting the unity of the family. This is same logic Mizulina uses in her attempts to abolish already existing legislation that makes familial battery a criminal offense.

“They argue children will start complaining about parents spanking them, and thousands of mothers and fathers will be subject to criminal prosecution,” Popova says.

Yet such worries are mostly groundless. According to Mari Davtyan, a lawyer dedicated to defending victims of violence, the number of cases against parents beating their children is unlikely to change: “Attackers of several social groups — children, the disabled and the elderly — have always been subject to criminal prosecution initiated by law enforcement.”

What the new legislation has done, however, is protect many vulnerable women. For the first time, law enforcement bodies can initiate prosecution of an offender. Before, prosecution was subject to private charges. Not only had the victim to sue the offender herself, she also had to collect necessary evidence, ensure witnesses would come to court hearings and so on.

Moreover, police are now likely to investigate domestic violence cases with more enthusiasm. District police officers usually dealt with such cases, but they didn’t have the power to open criminal cases and act upon evidence and testimony they collected, says Davtyan. “Police officers we work with were very much encouraged by this legislation,” she says.

Russia does not issue restraining orders to offenders — a measure that has proved effective in 140 countries, including Belarus and Uzbekistan, the lawyer adds. These orders can prevent an offender from approaching the victim, stalking her or in any way communicating with her.

However, the mere fact that domestic violence remains a criminal offense sends the right message: beating your wife and children is wrong, and for that you will be punished.

Today, the Russian old-world mindset still remains the biggest obstacle for victims of domestic violence.

If a woman decides to leave her abusive husband or report him to the police, often her own relatives will disown her. “They would say that keeping the family together and standing behind the father of her children is more important,” says Anna Center’s Larisa Ponarina.

Sometimes, women themselves will refuse help. “I often hear my neighbors, a middle aged couple, fighting,” says a Moscow resident speaking on the condition of anonymity. “Every time I call the police, the wife, with bruises all over her face, shouts at officers, saying it is none of their — or my— business. Once they tried to arrest the husband, and she went in fists first.” Such incidents clearly demotivate police from making crucial interventions.

When it comes to child abuse, the same logic works, says Anna Mezhova, head of Saving Life, a foundation that deals with violence against children. “When a child is being regularly beaten up or sexually assaulted by his father, the mother often covers it up, thinking that there is no need to air the dirty laundry in public,” says Mezhova. “But the behavior makes it almost impossible to protect the child.”

Blaming the victim is another major trend that allows abusers to get away scot-free and often lands victims behind bars, says activist Popova. Dozens of women end up standing trial for actively defending themselves during a fight. “Imagine: the husband was beating her up aggressively, she tried to defend herself and injured him. She stands trial for it now, whereas her lawsuit against him was dismissed! The judge did it on the grounds that the woman failed to show up for a hearing — which she, in fact, was just 15 minutes late for,” Popova says.

However, the activist believes that Russian mentality is slowly beginning to change. At the very least, women are now taking offenders to court, she says: “They support each other in court, and they feel confident enough to demand actions from law enforcement.”

So far at least, the statistics tell a discouraging story. According to a report by the UN Committee for Human Rights, the incidence of domestic violence is, in fact, on its way up. In 2015, the number of domestic assaults on women and children grew by 20 percent compared to a similar reporting period in 2010.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.