The killing of journalist Pavel Sheremet shocked everyone who knew him. Belarussian by nationality, Russian by citizenship, and most recently a resident of Ukraine, Pavel was not afraid of speaking his mind and criticizing the powerful. Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenko (who revoked Sheremet’s citizenship in 2010), President Vladimir Putin and the Ukrainian government all found themselves on the receiving end of his work.

Sheremet was more biting commentator than muckraking journalist. Now, however, his name stands alongside pioneering investigators such as Anna Politkovskaya and Natalya Estemirova of Russia, and Georgy Gongadze of Ukraine, founder of the Ukrainian Pravda newspaper for which Sheremet would later work.

He was killed by a bomb, which had been placed under the driver’s seat of his car. Were there any warning signs that such a grotesque attack would happen in Ukraine?

The first thing to say is that Ukraine today is in profound political crisis. As a Reporters Without Borders report noted in May, the media is a significant part of that crisis. Ukrainian journalism is rapidly losing the confidence of the Ukrainian people.

What that report failed to mention, however, was how both politicians and the public have stigmatized journalists in the last year.

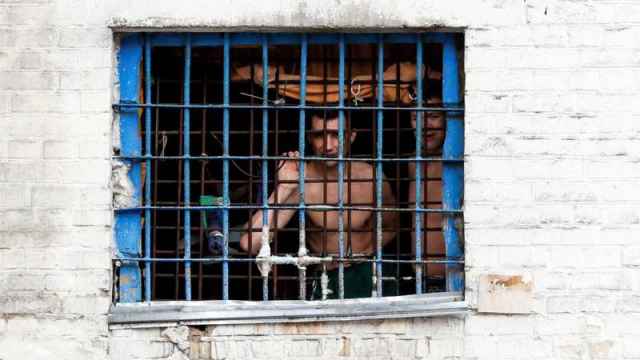

In May, a website called Mirotvorets (Peacekeeper), which claimed to be devoted to the “struggle against the Russian threat,” came to public attention when it published the personal details of 4,500 journalists, complete with phone numbers and e-mails. The website’s creators accused the journalists of collaborating with DPR terrorists. The basis of these claims were that the journalists had received accreditation from the leadership of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR). The list contained not only local media workers, but also many of the world’s leading correspondents. Hardly surprising, given the fact that working without accreditation was a surefire invitation to prison and worse.

A great number of the listed journalists soon began receiving threatening letters and phone calls. Accusations that they were “accessories to terrorists” appeared on social networks along with calls to revoke their right to work in Ukraine. “Bot attacks began and a barrage of threats,” said Ukrainian Information Policy Deputy Minister Tatyana Popova. “They called us anti-Ukrainian journalists that are aiding the enemy.”

Anton Geraschenko, an Interior Ministry adviser and member of parliament, believed by some to have played a role in instigating the publication, called for new censorship laws to counter Russian propaganda. He proposed establishing control over the content of licensed television channels, requiring accreditation for foreign media operating in Ukraine, and blocking Internet sites that “incite hostility, hatred, and undermine national security.”

Geraschenko referred to the Mirotvorets site administrators as “patriot hackers, united by the desire to protect their country by the means available to them.”

The incident received wide international coverage. The Ukrainian president spoke out in support of the journalists and Ukraine’s State Security Service promised to look into the matter. The Interior Ministry was the only government agency to say nothing, while Interior Minister Arsen Avakov referred to the journalists as “liberal separatists” in a Twitter post.

A confrontation between liberals and “patriots” has split Ukraine for two years, with journalists the main victims of the division. Officials were the first to harass them, but after Mirotvorets published its list, ordinary citizens joined the attack.

Another serious incident occurred when reporters from the Ukrainian independent television channel Hromadske.ua and Russian Novaya Gazeta correspondent Yulia Polukhina filmed DPR forces using heavy equipment banned by the Minsk Agreement to shell Ukrainian troops at the front in Avdeyevka in the Donetsk region. Two Ukrainian soldiers died in that clash.

Before publishing the footage, the Hromadske.ua reporters submitted the video to soldiers to confirm that its publication would not reveal the position of government troops. The next day, however, military officials accused them of doing exactly that, even though only Novaya Gazeta had posted the video — and then only in response to the deaths of two Ukrainian soldiers.

The story developed into a major scandal. Soon after, Interior Minister Anton Geraschenko blamed Hromadske.ua for the deaths of the soldiers. That prompted the wave of threats against the journalists that continues to this day.

“We have grown accustomed to the fact that bots, spin doctors, and trolls work for various political forces and struggle against each other to create fake public opinion,” says Hromadske.ua managing editor Angelina Karyakina. “Now, the authorities are using the same tools against those whom they deem undesirable — primarily independent journalists. We believe that by accusing journalists of helping the enemy to correct the trajectory of its guns, the authorities are trying to silence their voices,” she said.

Karyakina said that Ukrainian officials were adopting Kremlin techniques for manipulating public opinion. Denis Krivosheyev, deputy director of Amnesty International for Europe and Central Asia, agrees.

Unlike Russia, however, the threat against the media community in Ukraine has not become unofficial state policy. Head of the Institute of Mass Information NGO Oksana Romanyuk believes the level of aggression has actually declined since 2014, when the war was in full swing and society was caught up in it. New trends have since appeared. Oligarchs realized they can do as they please, and that they can go back to using the media outlets under their control to promote their own interests. And the media now has a negative image, so that journalists are hindered and threatened.

But the murder of Sheremet in central Kiev goes against any positive trend. No one of this prominence has been killed in Ukraine since Gongadze was murdered in 2000.

The public stance that politicians and senior security officials have taken against independent journalists probably contributed to this tragedy. No matter who ordered this terrorist act, it has benefitted those politicians who publicly call for censorship and discredit the media. The killing of Sheremet intimidates all journalists and, therefore, is a threat to democracy.

The question now is whether Ukrainian society can defend the country’s media rather or, instead, remain a passive tool of cynical politicians seeking to manipulate public opinion.

Katerina Sergatskova is a Russian-Ukrainian Journalist working in Ukraine.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.