When Moscow city deputy Alexandra Parushina asked the men in bulldozers if they had permission to tear down a 1920s housing estate in her constituency on June 6, security guards threw her to the ground. While they held her down, injuring her leg, the demolition began. "Bricks were literally flying over our heads," said Parushina.

Parushina was still in shock when she spoke to The Moscow Times. "I have never dealt with force before," she said. "They laughed and told me to stand up when they knew my leg was badly hurt."

Parushina had been campaigning to save the housing estate in the central Moscow Khamovniki neighborhood. The group of buildings on Pogodinskaya Ulitsa made up one of 26 "workers' villages" built in the capital during the 1920s in the "constructivist" style, a Russian architecture movement that combined geometrical shapes, new technologies, and communist ideology. In 2012, they were included on Moscow's register of cultural buildings. But in June 2015, a government commission gave developers the green light to demolish the buildings and evict the residents of Pogodinskaya. "It is criminal, these are architectural gems," said Parushina.

What made Pogodinskaya valuable to investors was its location — a stone's throw from the Moscow River and close to the heart of the city. Its place on the map also made it valuable to activists defending Moscow's avant-garde heritage: It faced an iconic worker's club designed by pioneering Russian architect Konstantin Melnikov. The housing estate and club, activists argued, made up one integral architectural group. Following demolition, Pogodinskaya will be replaced with an elite housing complex, which Parushina says will disrupt the view of the Melnikov building.

The future of the workers' club, known as the "Rubber Factory Club," is unclear. It has been repeatedly threatened with demolition and currently stands empty. Most of the buildings that Melnikov designed to worldwide acclaim — garages and workers' clubs with his trademark exterior staircases — are in a terrible state. The only successful example of a renovated Melnikov building put to modern use is his 1927 Bakhmetevsky bus garage that currently houses Moscow's Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center. The rest are either semi-abandoned or reconstructed beyond all recognition.

The workers' villages and Melnikov designs are not the only vulnerable constructivist buildings in Moscow. Much of the Russian capital's early Soviet heritage is disappearing fast. Being a monument of constructivism is not in itself deemed worthy of salvation by the Mayor's Office.

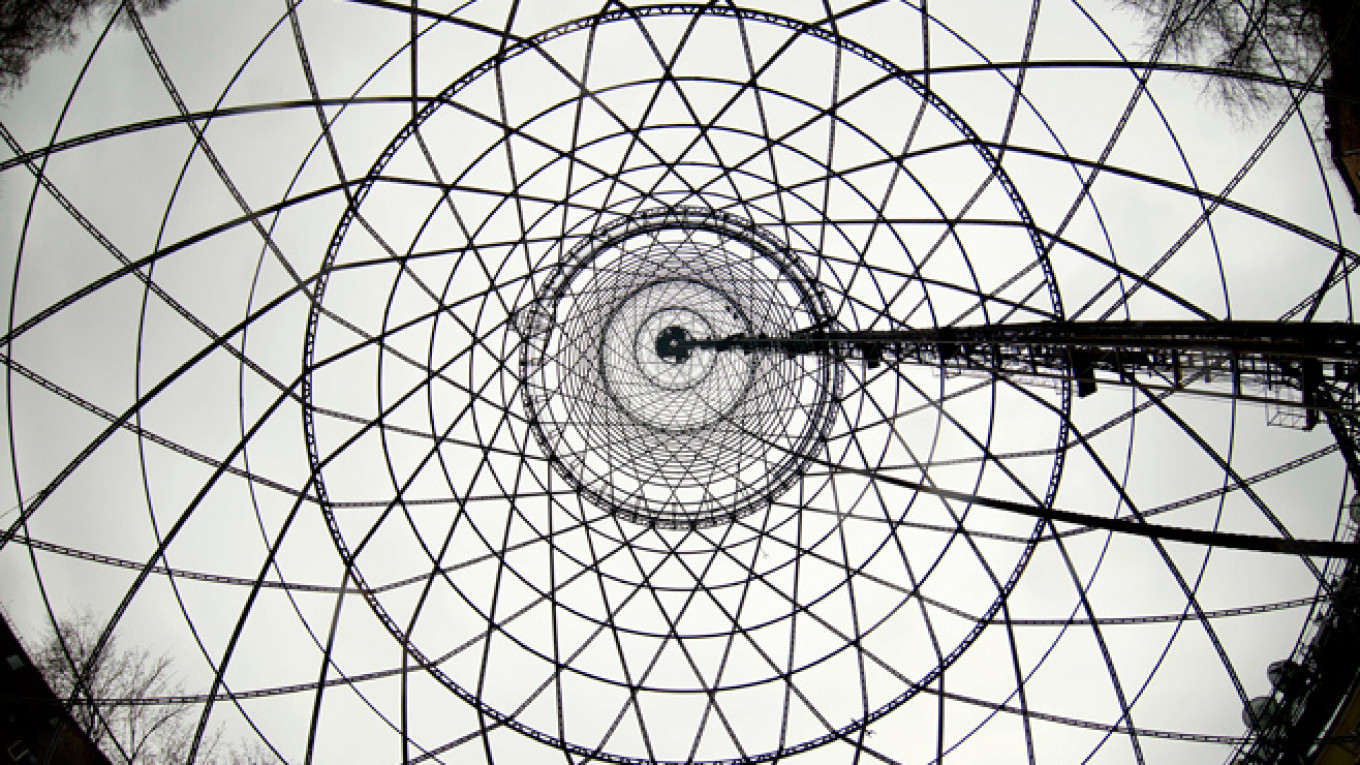

An interior of Moscow's Melnikov House, completed in 1927-29. The well-known building is made up of two cylindrical towers decorated with hexagonal windows.

Disappearing Landmarks

Two months earlier in another part of the city, authorities abruptly began the demolition of another constructivist landmark, the 1929 Taganskaya telephone station. They did so despite public protests, a petition to the Moscow mayor that garnered over 30,000 signatures and the opposition of leading Russian architects. Even activists were surprised to see how many people took to the streets to defend the building, which was not one of Moscow's best-known constructivist monuments.

However much Moscow's creative class protested the decision, it was to no avail. A luxury housing complex "in the late 19th-century Art Nouveau style" will now be built in its place. In an interview with the Vedomosti newspaper, the investor heading the project said the protests were "organized to gain political points" and that the building "would have collapsed in five years anyway."

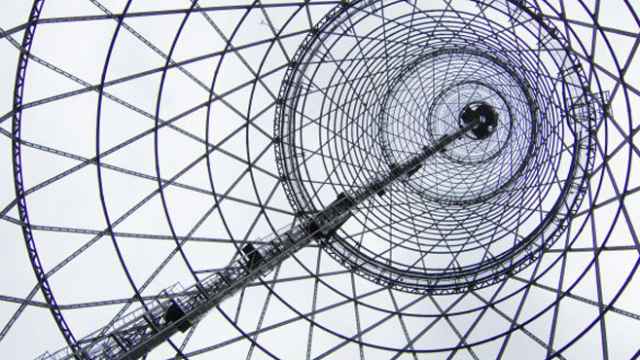

Architecture historian Alexandra Selivanova has become a prominent figure in the campaign to save Moscow's avant-garde heritage. "You can't just sit and write books when the object of your study is disappearing," she said in an interview on the balcony of the Avant Garde Center, an educational platform dedicated to early Soviet modernism, which she founded. The center is based in a local library in Shabolovka, the central Moscow neighborhood where Selivanova lives. Shabolovka is also home to several celebrated constructivist structures, including the Shukhov Tower, a 1920 broadcasting tower designed by Vladimir Shukhov.

Selivanova's fight to save 1920s Moscow began with the Shukhov Tower. In 2014, Moscow authorities announced plans to move it. Selivanova helped lead a successful campaign to keep it in Shabolovka and demand its restoration. However, its future also remains unclear.

The structure belongs to the Russian Television and Radio Broadcasting Network, overseen by the Communications Ministry. The ministry wants to transfer responsibility of the disused tower to the Culture Ministry, which, in turn, says it will only agree if the former uses allocated funds to renovate the landmark. "While they fight between each other, the tower is rusting," says Selivanova. The Federal Service for the Protection of Cultural Heritage has proclaimed recent stabilization works as a victory, but Selivanova says it was carried out without expert consultation and risks damaging the tower further.

Ticking Boxes

Activists have expressed concern over new regulations they say make it almost impossible to prove, in a legal sense, that constructivist buildings are worth saving. In December 2015, Moscow authorities introduced a point system designed to qualify the cultural status of a building. Under these new rules, a building must have 200 points to be included on the state register of cultural heritage. Despite being in good condition, the Taganskaya telephone station wasn't awarded enough points by the government commission, which granted the building only 176 points. An independent committee, however, granted the building 276 points using the same criteria.

Selivanova argues that the system rates historical and political significance above architectural value. "If Lenin once set foot in a building, it automatically gets 50 points. It is absurd," she says. She also complains that the system prioritizes ornate buildings, thereby disadvantaging the more minimalist modern architecture. "They operate by ticking boxes, but you cannot judge a building in this way," says Marina Khrustaleva, an expert on constructivism.

Shortly after plans for Taganskaya's demolition were announced, the nationwide non-governmental organization Arkhnadzor, which campaigns for the protection of historic buildings, organized a protest against the destruction of Moscow's architectural legacy. An estimated 700 people attended the event on Moscow's Suvorov Square. Many carried banners bearing caricatures of Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky and anti-oligarch slogans. Protestors demanded that the authorities give Moscow the status of a historic city and stop rejecting expert opinions on the value of buildings.

The call to save constructivist buildings dominated the protest. Arkhnadzor will soon publish an interactive guide of 120 historic buildings under threat in Moscow, 15 of which are part of the constructivist movement. "Twentieth-century buildings are harder to defend because people think they are not that old and thus not valuable," says Ksenia Apel, 36, an art historian who attended the protest because she is worried about the future of a 1920s ballet school in her local Khamovniki district.

Despite objections from hundreds of local advocates, demolition of the Taganskaya telephone station began in April 2016.

Decades of Neglect

Constructivist buildings were neglected for much of the Soviet period, and renovating them is a daunting — and expensive — task. "By the 1930s, they were already rejected for being insufficiently decorative and too Western," says Khrustaleva. During perestroika, she says, the architecture was associated with the worst of the Soviet past. Authorities say the buildings are badly planned and, unlike Stalinist architecture, built using poor materials. Selivanova admits that is true for some of Moscow's constructivist landmarks, but maintains that the crumbling state of the buildings is primarily due to decades of neglect.

Russians' bad memories of the 1920s, Selivanova suggests, keep them from appreciating early Soviet architecture. "People associate this period with hunger and social experiments," she says. Stalinist architecture is more popular: "It's festive, and reminds people of the propaganda films of the 1930s and 1950s, which still make an impact today."

Russian-American campaigner and photographer Natalia Melikova has been documenting the disappearance of constructivist Moscow since 2010. She believes that while Moscow's historic architecture from all periods falls victim to destruction, the city's authorities have especially consigned constructivist buildings to the scrap heap.

The buildings were particularly despised by Yury Luzhkov, mayor of Moscow from 1992 to 2010, who, according to Khrustaleva, dismissed them as "flat-face architecture." The city's current mayor, Sergei Sobyanin, is often portrayed as having a more progressive vision for the Russian capital than his predecessor, but his team seems to share the same approach toward constructivism. "I personally believe these buildings should be left as monuments of how not to build," the city's deputy mayor for urban development Marat Khrusnullin, told an investor forum last week. To the activists' dismay, he added: "We should leave two or three of them."

Many of the few "renovated" constructivist buildings have in reality been stripped of their original ornamentation. The only example of a genuinely successful renovation of a constructivist building in Russia, Selivanova says, is the central library in Vyborg, a small town in the Leningrad region near the Finnish border. "And that was fought for by the Finns," she says.

The renovation of the library, which was designed by Finnish architect in 1920, had been in planning for years but was only undertaken after President Vladimir Putin visited the medieval town with Finland's then-President Tarja Halonen in 2010. Soon after the meeting, Moscow released the funds for the renovation.

Activists worry that the rest of Moscow's shrinking population of constructivist buildings will suffer the fate of the Taganskaya telephone station. "The situation escalated so quickly, they didn't listen to anyone," Selivanova says. She sees it as her mission to convince Moscow authorities that these buildings are worth saving.

"The problem," she says, "is that destruction is faster than persuasion."

Contact the author at [email protected]. Follow the author on Twitter at @olacicho

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.