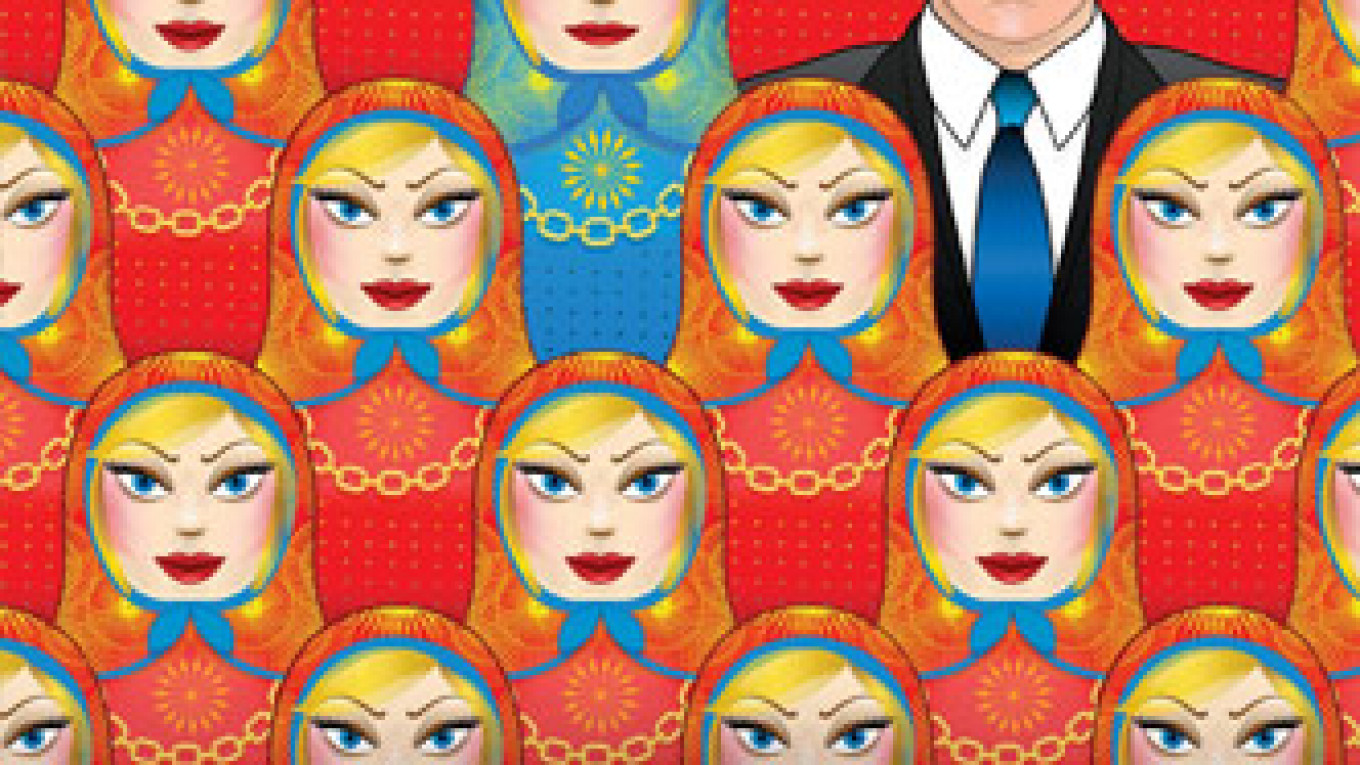

Author Rebecca Strong is originally from the former Soviet Union but has lived in the United States and Europe since the 1980s. It was on a trip to Russia after years away that Strong — a pseudonym — came up with the idea for her debut comic novel, "Who is Mr. Plutin?" "What if I write a novel whose protagonist ends up in Russia with no recollection of getting there?" Strong asked in an essay she published in the online magazine Quartz. "The novel I was writing took place in Russia, mocked the oligarchy, and featured caricatures of those in the highest echelons of Russian society," she said. Behind the veil of fiction and under the protection of a pen name, Strong has created the Russia that she knows — with both an insider's understanding and an outsider's incredulity.

"Who is Mr. Plutin?" joins a well-loved tradition of waking-up-in-another-body stories. In most of them, the switch is fun for the hero at first, but soon enough comes a yearning for his previous life and familiar self.

"Who is Mr. Plutin?" doesn't play it that way. Sad-sack single Vika Serkova goes to bed in her cramped New York apartment and wakes up the next morning in a swanky flat in St. Petersburg, Russia. She's not particularly eager to get back to her old life. "I would not say it's all bad," she thinks. "I have a great apartment, a car, a handsome husband, powerful parents who seem strangely proud of me, and … a maid. That's right." New York quickly fades behind the glamour and glitz of high society St. Petersburg.

As the daughter of immigrants, Vika can speak Russian fairly well, so she muddles her way through her new reality, even though she feels "like a reincarnated newborn who still has memories of the previous life." But Vika cannot revel in caviar and Birkin bags for long. She soon becomes aware of the most startling aspect of her new Russian identity: she's a spy. It's in Vika's best interests to play along. If they say she's a spy, she'll act like a spy. She's read enough James Bond novels to put on a pretty good show. She even seems to have a knack for it. "Blackmailing must have been my best subject in spy school," she muses.

Although her memory is still on the fritz, she struggles to complete her assignments, which seem to be coming from the president, Mr. Plutin, himself. Mr. Plutin may as well be a "Russian Dr. Evil" — one of Vika's many disparaging nicknames for him — but he's also extremely dangerous. "I would bet my entire designer closet that not many people crossed Plutin's path and lived to tell about it," Vika says. She must find a way to get herself and her family out of the predicament they find themselves in. And therein lies the tale of the novel.

"Who is Mr. Plutin?," like its heroine, seems to suffer from a bit of an identity crisis. The book can't decide if it wants to be written by Candace Bushnell, Agatha Christie, or Gary Shteyngart. This intentional mix of chic lit, mystery and biting satire may have some of the uneven tone of a first novel, but it's original and funny, with some real flashes of insight into today's Russia. "Who is Mr. Plutin?" is good light reading for dark times.

Rebecca Kelley lives in Portland, Oregon, where she writes and teaches at Oregon College of Art and Craft.

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.