In Ukraine, whose tumultuous 20th-century history has spilled over into a bloody battle for its 21st-century identity, every picture tells a story.

Daisy Sindelar traveled to six Ukrainian cities to talk to people about what their old family photographs say to them about who they, and their country, are today. This week, Anastasia Aslanova, 31, a product manager, tells her family's story from Kiev.

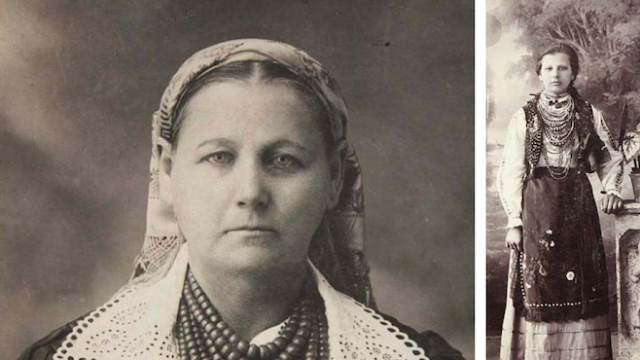

This article was first published by Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty as part of the My Ukraine project.A lot of people see my surname and think I have roots in the Caucasus. Actually, it's a Turkic Greek name. Catherine the Great brought a lot of Greeks to Crimea after defeating the Ottoman Turks, to get more Orthodox Christians into the region. Both of my father's grandfathers were Greek Ukrainians. They lived in Mangush and Starobeshevo, near the Azov Sea, where a lot of Greeks resettled after living in Crimea.

Stalin, as we know, liked to play with nationalities. He wanted to destroy Ukraine as a nation, so he started by starving people to death during the Holodomor. Then he deported the Crimean Tatars to Central Asia and started getting rid of the Greeks, as well.

One of my Greek great-grandfathers, Timofiy Aslanov, was taken away in a black car and never came back. Just a few years ago, I found a document that said he had been executed. In the space where they give the reason for the execution, someone had written: "Greek." That's it.

My great-grandfather's arrest was quite hard for his family. It was never good to be related to an enemy of the state. My grandfather, Arkadiy, was well aware of this, and when World War II began, he tried to get drafted into the Soviet Army.

He was only 15, but he ran away from home and lied about his age, hoping that if he served in the military it would somehow help him and his family.

It didn't work, though. They figured out how young he was and wouldn't let him enlist. So he had to go back home, and that made things even worse, because if you stayed in Ukraine under the German occupation it was easy to accuse you afterward of being a collaborator.

Varvara Aslanova with her three children (L-R) Arkadiy, Halyna, and Yevhen, circa 1939.

To make matters worse, one of their neighbors reported that Arkadiy had drawn a picture of Hitler with his finger in the fog on a window. That was all the proof they needed that he was a Nazi sympathizer. He was arrested and sent to a labor camp in the Far East for 10 years.

It was there that he met my grandmother, Emma, a nurse in the labor camp. She was also from Ukraine, from Odesa. Her father was Jewish and her mother was Bulgarian.

Her story is a little like Arkadiy's. During World War II, she had also run away from home. Her mother had died and her father married a woman who was abusive to Emma and her brother. She burned her passport to hide her age and volunteered to serve as a surgical nurse. She was 16.

Emma Vainshtein with her mother and brother, Yan, Odesa, 1932.

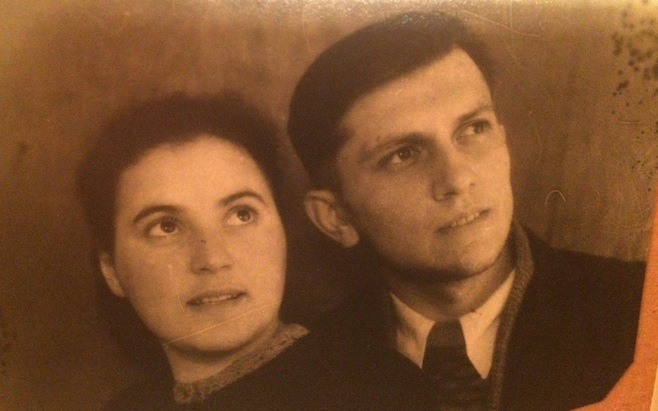

They wanted to send her to the Japanese front, but she only made it as far as the Far East. She was able to earn a pretty good living there, and she had some special privileges. When she met my grandfather, she was able to provide him with a double ration of food. I'm sure it was still nothing, but it probably helped keep him alive. It was very cold and damp there.

My grandparents never talked about life at the prison camp. Never. Even my father refused to talk to me about it. He would always joke and say that those old stories were boring. It took a long time to hear those stories. I realize now they were trying to protect me. They were afraid that if I knew the truth that it would put me at risk as well.

They had a few photos from the camp, but they never talked about the people in the photos, or wrote to them. This kind of fear lasts for decades. You can't imagine living inside this strange world, where you can't trust anyone, and any day they might take you away because somebody once drew something on a window.

Arkadiy Aslanov (R) performing at a magic show with a fellow gulag prisoner, circa 1946.

My grandparents were eventually allowed to come back to Ukraine. But their lives were always going to be compromised by the fact that Arkadiy was the son of an enemy of the state and had served time in the gulag for collaboration.

They weren't allowed to live in a big city, for example. They spent one night in Dnipropetrovsk, at the home of a relative. But after that they had to get on a train and go outside the city. They had two suitcases and an 8-month-old baby.

They got off at Novomoskovsk, about 30 kilometers outside Dnipropetrovsk. It was winter. My grandparents always remembered getting off the train and standing on the platform, looking up at the moon -- there was a very big moon that night -- and thinking, "OK, what now?"

Emma and Arkadiy Aslanov, circa 1950.

My grandfather had learned how to paint at the labor camp, and he found a job painting Soviet art for a local factory. You know, portraits of Soviet leaders, posters for Soviet holidays or Communist Party congresses, that sort of thing. Not exactly what he wanted to be painting.

In the 1990s, the factory newspaper printed an article saying, "The honest name of Aslanov has been restored." He had been officially rehabilitated.

Almost everyone in the former Soviet Union has a story like this in their family. So when the truth finally started to come out, we thought for sure that people would never let history repeat itself. In Ukraine, people are pretty much united in thinking of Stalin as a monster. So it's shocking to realize that Russians really like Stalin! They think he did good things, and they want those things to happen again, to their country and all the countries around them. I have relatives in Russia that I can't even talk to anymore.

We were surprised by Euromaidan. After the Orange Revolution, people sort of had the idea that those protests wouldn't work anymore. But the Maidan was very organic. And once police started beating students, it was enough to make the whole country go crazy.

I think the future in Ukraine will be great. The question is when.

Anastasia Aslanova with her husband, Mykhaylo Byelosotskiy, standing outside Independence Square. "During the Maidan, it was much scarier to stay at home than go to the square. At home, you were on your own. At the square there was something to do."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.