Events in international politics undoubtedly have their own internal logic, and it is no coincidence that Moscow chose to officially withdraw from the Treaty on Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) just as a new Cold War is taking shape, thereby raising the specter of a direct military confrontation with Europe.

Moscow formalized that decision by announcing that it would no longer participate in the CFE Joint Consultative Group, the last body charged with implementing that treaty in which Russia had still been active.

That might not seem so terrible at first glance. The CFE lost all practical value many years ago, and was already a moot point by the time it was finally signed in 1990. In fact, negotiations on limiting conventional armed forces began in Vienna in 1973 and continued there for a full 20 years.

Soviet military diplomats — some of whom were lucky enough to spend their entire careers in the Austrian capital — joked at the time that the best way to speed up the negotiation process would be to move them to Murmansk. But in truth, they faced a difficult task: negotiate restrictions that would prevent NATO and the Warsaw Pact from concentrating sufficient military forces for aggression — even in the event of a direct military confrontation.

The result was a treaty setting limits on the deployment of heavy weapons such as tanks, armored vehicles, combat aircraft and artillery systems on either NATO or Warsaw Pact territory.

It also established limits on so-called "flanking" movements whereby one side concentrates major military units so as to strategically outflank and seize control over the other. After living through two world wars, Europe could now feel confident that any future conflicts would not be resolved by force.

Only a few months after signing the CFE, first the Warsaw Pact and later the Soviet Union itself collapsed. However, transparency and mutual security guarantees remained of principle importance to European states, and so a modified version of the treaty was developed in 1999 that set limits not for military alliances, but for each individual country.

The resulting document was advantageous to Russia in that it set limits surpassing the number of heavy weapons held by the Russian army.

At the same time, the 1999 version of the CFE Treaty also obligated Russia to withdraw its armaments from Georgia and Moldova. Moscow, however, did not comply with those requirements. In response, NATO member states did not ratify the revised CFE, although they continued to comply with the limits it set — and continue to this day.

However, the Kremlin felt that NATO had deliberately humiliated it by refusing to ratify the CFE, and in 2007 it cited certain "extraordinary circumstances" to justify suspending its participation in the treaty — ceasing to regularly inform the other European states of the composition and deployment of its troops.

Of course, it was no accident that such a move occurred almost simultaneously with President Vladimir Putin's famous speech in Munich in which he raised the possibility of a new Cold War between Russia and the West. From that moment on, the Kremlin began systematically working to achieve its objectives through military means. The Russia-Georgia war of 2008 provided proof of this shift.

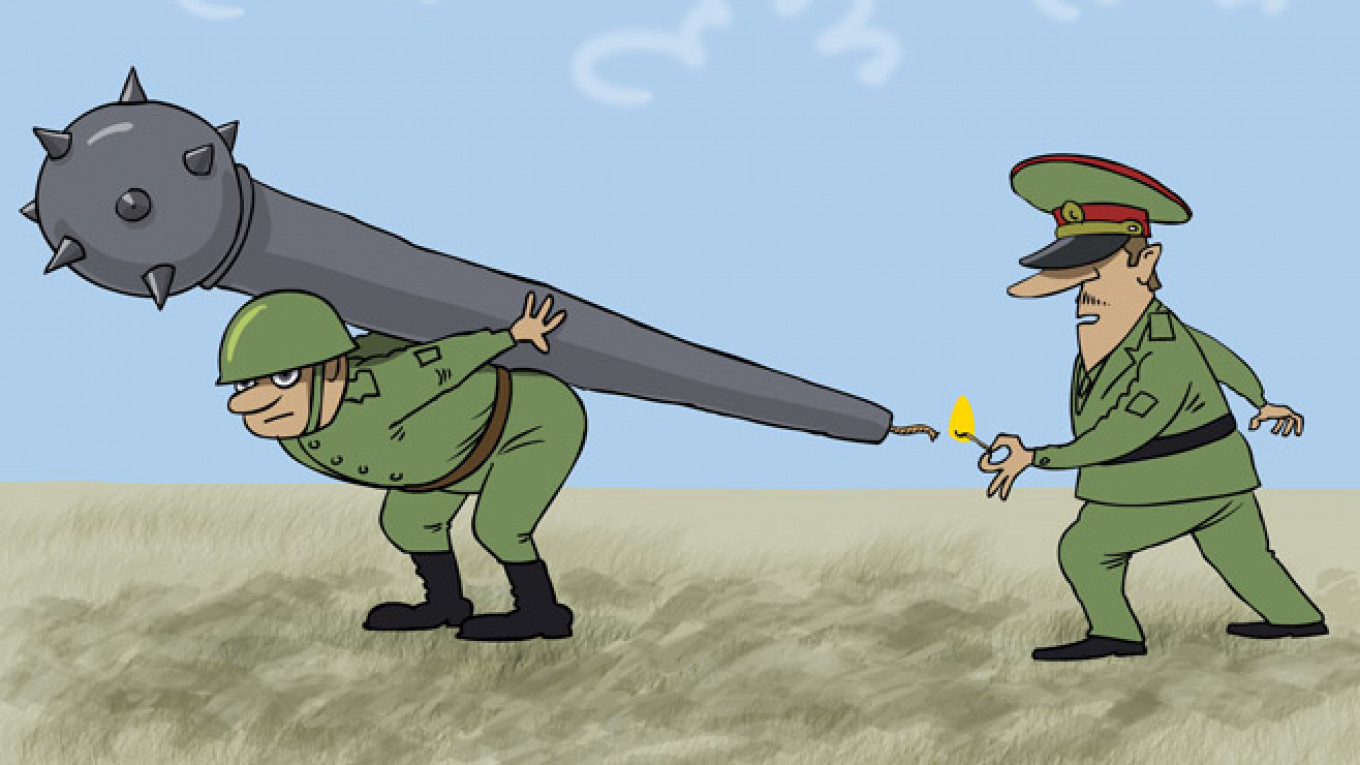

In hindsight, it is clear that Russia achieved a military advantage by refusing to comply with the CFE, enabling it to deploy troops to Crimea and the Russian-Ukrainian border. That is, it could accomplish precisely what the CFE was supposed to guard against: the secret concentration of forces as a prelude to aggression.

Moscow's decision to dispense with every pretense of abiding by the CFE provides further evidence that a new Cold War is rapidly approaching. And although, for now, the Kremlin is reveling in tearing up a treaty that dates back to the 1990s, the consequences of that action will not be slow in coming.

The CFE is not simply an outdated set of binding procedures as the Kremlin contends, but the embodiment of a principle. It is the principle that potential adversaries can guarantee their mutual security by committing themselves to transparency in military activity and mutual trust.

Today, Russia has rejected that principle. That leaves only one way to achieve security in Europe — military deterrence. Now, the two sides will build up a balance of military power meant to convince the other that they would suffer unacceptable damage if they attacked.

As a demonstration of this, U.S. forces are now deploying to the Baltic states. I clearly recall the 1980s when the U.S. conducted its yearly Autumn Forge maneuvers deploying 1,300 tanks and tens of thousands of soldiers to Europe. The current situation has not reached that point yet, but then, this Cold War has only just begun.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.