The Russian mentality tends toward two annoying extremes: conceit and self-deprecation.

Even classic Russian historian Nikolai Karamzin suffered from the former of those character defects. He wrote: "Russia alone is authentic, only Russia truly exists; everything else is measured by its relationship to Russia — and those are but phantom thoughts."

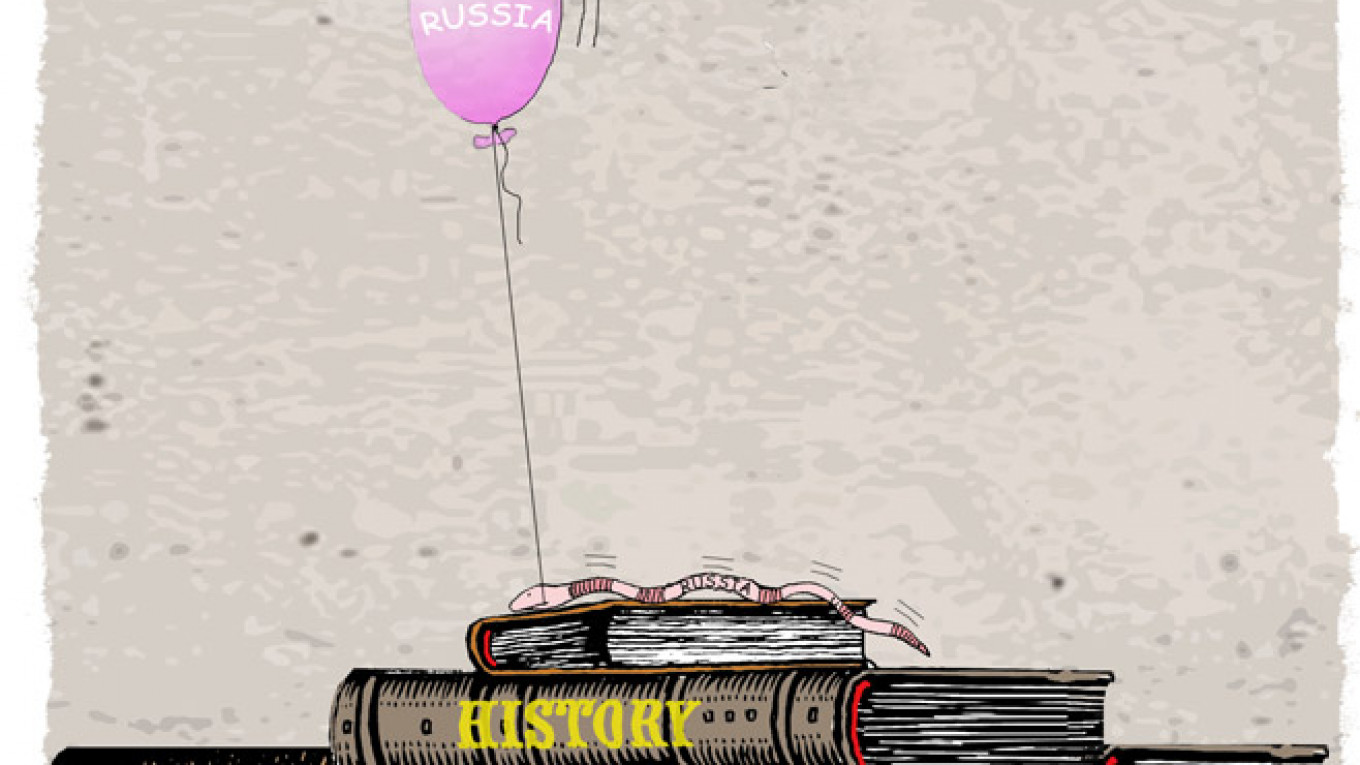

Karamzin did not reach that conclusion quickly, but only after passing through stages in what many have called "Solovyov's ladder," in honor of philosopher Vladimir Solovyov. Solovyov's philosophy may be distilled into the following stages: national identity — national conceit — national self-adoration — national self-destruction.

Here is how Karamzin progressed — or regressed — along these gradations of thought. During stage one in 1790 he writes: "Everything concerning specific peoples is as nothing before our common humanity. It is more important to be a human being than to be a Slav. That which is good for people generally cannot be bad for Russians; and that which Englishmen or Germans invented for the benefit of all people is also of use to me because I am a person!" His words here contain no trace of self-deprecation or pride, and I would gladly ascribe to such sentiments myself.

In stage two in 1802 Karamzin writes: "By connecting us with Europe and showing us the benefits of education, Peter the Great only briefly dampened Russian national pride. With only a glance at Europe, we assimilated the fruits of its long years of labor. … Soon others could, and had to, learn from us; we showed how to beat the Swedes, Turks and finally, the French. All of those glorious republicans who speak better than they fight, ran from the first thrust of Russian bayonets. We know that we are braver than many, but do not know any that are braver than us." That is already conceit.

In 1811, in stage three, he writes: "Looking at our own history. Do we confirm the uninformed opinion of strangers and say that Peter [the Great] made our state great? Will we forget the princes of Moscow? By throwing out the old ways as ludicrous and praising and introducing foreign ones, the Russian sovereign debased the Russian people in their own eyes. Russia has existed for approximately 1,000 years … in the form of a great state, and everyone harps on us … about new rules, as if we just emerged from America's dark forest!" At that point, Karamzin was just one step away from self-adoration, and Nazi Germany has shown us that self-adoration leads to self-destruction.

Fortunately, Russia has never sunk that far. The low point of Russian nationalism came under Tsar Nicholas I, who, comparing Russia with the West, claimed that Russia's "imperfections are, in many respects, better than their [Western countries'] perfections." Thank God, such thoughts do not dominate in modern Russia, but they do exist and they are dangerous because it is a simple matter to slip from one rung to the next in "Solovyov's ladder."

But there is another extreme from which today's pro-Western political opposition in Russia often suffers. Philosopher Nikolai Berdyayev described pro-Western Russians in this way: "The radical Western-oriented Russian intelligentsia has always contained a great deal that is not only alien to the West, but that is completely Asian. European thought was distorted beyond recognition in the consciousness of the Russian intelligentsia. Western science and the Western mindset were deified in a way that is unknown to the more critical West."

Famous Russian philosopher Pyotr Chaadayev — who, by the way, was also from the era of Tsar Nicholas I — still has the best description of the most extreme position in that camp. He wrote: "Alone in the world, we gave the world nothing, took nothing from the world and contributed nothing to the forward movement of human thought. … There is something in our blood that rejects any real progress."

There is no great need to refute the absurdity of these statements because history itself refutes them, as do Russia's considerable contributions to the world's development in the fields of literature, music and science. Even Chaadayev himself later rejected those ideas, a fact that today's radical pro-Western opposition prefers to forget. In a letter to the historian Alexander Turgenev, the philosopher writes: "I am of the view that Russia is destined to perform an immense mental task — to one day resolve all of the questions causing controversy in Europe."

That might be an exaggeration, but one thing is certain: We should not deify or deprecate Russia. This country might be no better than others, but it is definitely no worse. It will therefore be better for everyone if we content ourselves with simple self-respect.

Pyotr Romanov is a journalist and historian.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.