Everyone knew what was in the redbrick 19th-century building by Red Square in Soviet times. It was the Lenin Museum, the home — together with the nearby mausoleum — of the Lenin cult, to which a visit was a rite of passage for Soviet children, sculpting the ideological view of the Bolshevik leader with the help of the vast number of items kept at the museum.

The building stood closed for much of the last two decades, until the War of 1812 Museum opened there a few years back. It was only this year that the "Leniniana," as the museum calls the statues, paintings, clothes and documents connected to the Soviet leader, were put back on show.

The Lenin Museum's archives still exist and number 100,000 items, collected over about 70 years. A thousand of them are now on show in an exhibit called "The Myth of the Beloved Leader." As the title suggests, the Lenin on show now is shorn of ideology and as much about how the myth was created.

A number of items at the exhibit are on show for the first time, dug out from the archives, where they had been hidden by dedicated museum workers during the intermittent purges that hit the collection as political fortunes switched one way and then the other.

"Back then you got a hefty jail sentence for being 10 minutes late for work, and for that kind of thing [hiding artifacts] there would be a very serious sentence," said Olga Grankina, a museum employee who has worked there since 1976.

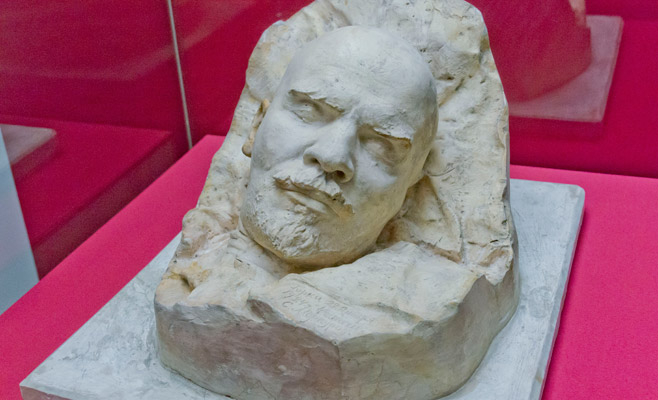

One such item is a bust of Lenin made by Maria Denisova-Shadenko in 1927, where he looks cunning and artful, more a lusty goat than the kind, brave father of the nation that Soviet ideology wanted to portray.

"I have huge respect for the courage of the people who did this, because it is only thanks to them that today's visitors can see them," Grankina said.

The collection of items connected to the founder of the Soviet Union began almost immediately after Lenin's death in 1924, but it wasn't until 1936 that the museum opened in the building on Red Square that had formerly housed the Moscow City Duma.

With Stalin firmly in power, the original exhibit was skewed to show how close Stalin was to Lenin, and purged of anything that could contradict that idea. Portraits were commissioned that had Lenin as the focus but Stalin, the devoted lieutenant and future leader, never far way.

In paintings of Lenin in the 1920s, Stalin was nowhere in sight, Grankina said. "In the 1930s he is always there."

In the 1950s, the museum was ideologically cleansed after Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin in a secret speech at a Soviet party congress.

"They decided to remove any mention of Stalin from the museum," Grankina said, noting wryly that there was a lot to get rid of as by then it was practically "the museum of Lenin and Stalin."

One victim of that purge was a painting of Lenin arriving back from exile at Finlandsky Station in Petrograd in 1917. Stalin is nearby.

"It ended up in the archive and was never shown again until today," Grankina said.

One room in the exhibit houses a huge painting by Isaak Brodsky depicting the opening of the second Comintern, the international communist organization, in Petrograd in 1920.

Lenin is at the center, making a speech to 300-plus delegates, including some of the world's most famous communist figures, such as Clara Zetkin, founder of International Women's Day, and John Reed, author of "Ten Days That Shook the World."

The painting, finished in 1924, was on show to the public for a while but never made it onto the walls of the Lenin Museum, as among the attendees are top Bolsheviks Grigory Zinovyev, Nikolai Bukharin and Lev Kamenev, who would be declared enemies of the people in the 1930s and executed.

"We could not show them. These people were rehabilitated at the end of the 1980s, but in my opinion they were never fully returned to history," Grankina said.

The painting was only unveiled in the Lenin Museum in the early 1990s when the museum, riding the wave of perestroika-era freedom, put on show items that did not fit in with the Lenin ideal, such as the Rolls-Royce he had tootled around in. Soon after, the new Russian state closed the museum.

The exhibit includes a number of Lenin's personal items, such as the coat he was wearing during an assassination attempt in 1918, complete with bullet holes. It was also on display in Soviet times, but things are viewed differently now.

Fanny Kaplan, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party — rivals to the Bolsheviks — was arrested and executed for attempting to kill Lenin.

Grankina remembers how museum workers got access to security service archives in the early 1990s.

"We found out that not one person, Kaplan, was arrested, but three," she said. "Kaplan was half-blind. She could barely see anything. Maybe she took part, but her chances of hitting Lenin were practically zero. She was shot, and the other two were let go."

Grankina points to a poster that appeared on the day of the assassination attempt. It says that the party will respond with mass terror against all the enemies of the Revolution. At the bottom is the time it was printed, just a few hours after the assassination attempt. "Is it not too fast? Only a few hours have passed, and this document has already appeared," she said.

The two Social Revolutionaries who were arrested but released denounced their fellow party members soon afterward, Grankina said.

A group of items that would never have been shown in the Lenin Museum are letters and pictures that were used to teach Lenin to speak again after his catastrophic stroke in 1922, which left him paralyzed down the right side of his body.

Soviet history showed that he lived and then suddenly died, Grankina said, "but really it was a very difficult period."

After he recovered, Lenin never went back into the room where he had lain ill, and he avoided his sister, who had helped him through his illness, Grankina said.

Once he died, "the man was turned into a mystical hero. His image was canonized and considered holy," the museum's curators wrote in a booklet published for the exhibit.

The cult produced some strange results, such as portraits of Lenin made from postage stamps, straw and grain, and even a microscopic drawing of Lenin on a single lentil. Party bosses soon put a stop to such frivolity, but Lenin statues mushroomed across the country. A commission in the 1930s tried to calculate how many Lenin statues there were, but gave up as they realized the impossibility of the task, Grankina said.

Grankina speaks passionately about Lenin and the exhibit, which runs till Jan. 13 — as do other members of staff at the museum.

"You can say that this collection has had a difficult fate: At the start it was in an ideological squeeze, and then it was closed completely. But it is a curious collection," she said.

"It is normal to preserve things, to keep them and think about them," Grankina said. "We want people to come here and think what happened in this country."

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.