Sixty-eight years have passed since the end of World War II. There are still traces of it here and there, but the general recollection is slowly sinking into the layer of archives and museums. The gap between wartime and younger generations is growing. Having been brought up in a relatively peaceful period, I am used to taking the absence of conflict for granted. I do not know much about the war; I am not physically scared of it.

Many say that it was the knowledge and fear of endured hardship and violence that prevented the U.S.S.R. and NATO from starting a new war with each other in the '60s. Listening to the memories of the World War II veterans, I cannot help but realize how costly and meaningful on many levels the victory over fascism was. The story of Duncan Harris, a British participant in the Arctic Convoy, is significant as important historical evidence of both heroism and international cooperation, which was brushed aside shortly after the war. It is also a fascinating story in its own right.

The Arctic Convoys were sea convoys consisting of merchant and naval ships whose aim was to deliver strategically important products, planes and ammunition to the U.S.S.R. It operated under the Lend-Lease program from August 1941 up to May 1945. The program was initiated before the opening of the Second Front and continued until the end of the war.

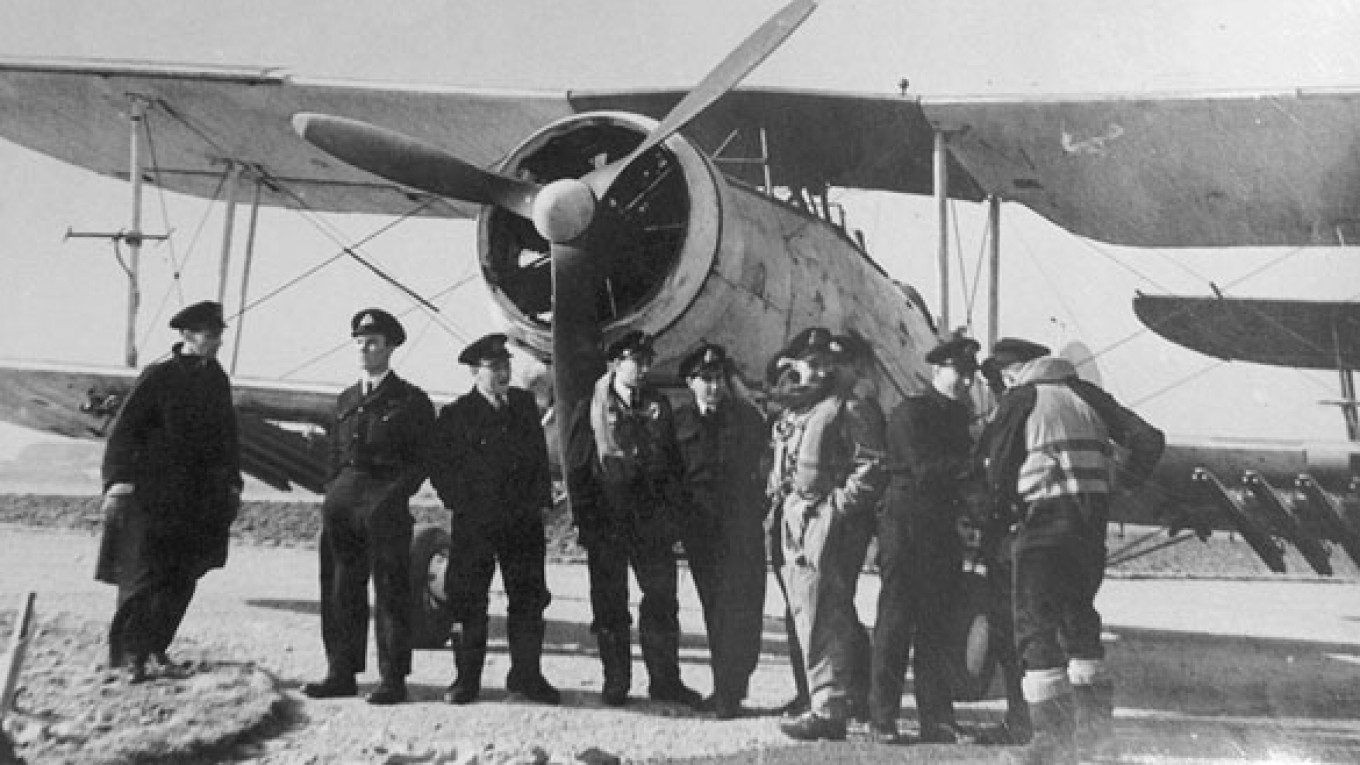

Former pilot Duncan Harris

The Arctic Convoys had an enormous impact on the course of the World War II, as they supplied almost 4 million tons of cargo to the U.S.S.R., goods that the Soviets desperately needed to continue the war effort. The Arctic corridor was the shortest, but also the most dangerous, route to northern Russian ports, primarily Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. The convoys sailed along the Norwegian coast and were an easy target for German submarines and the Luftwaffe. In a recent interview with The Moscow Times, veteran Duncan Harris recollected the Arctic Convoy journeys in which he participated.

Harris is 91 years old. In his long, eventful life, war did not feature as the most significant period, yet his memory of it is as clear as if it happened yesterday. He joined the military as a volunteer and was posted as a pilot to an escort carrier for the Arctic Convoy to Murmansk. Throughout 1944-45, he took part in four trips: JWRA 60, 62, 64 and 66.

Harris was not a member of the ship's company, but rather part of a squadron of Swordfish aircraft. The Swordfish aircraft had open cockpits and were affectionately known as "Stringbags." The squadron itself was based in the ship, flying off and onto its decks. Harris was an observer, or navigator, and flew in the back seat of the plane working sophisticated radar to spot enemy submarines.

"The most difficult part of our work was finding our way back to the ship," Harris said, adding that despite working in the Arctic, weather was rarely a serious factor in their journeys, "the job was the same in the Arctic as it was on the equator."

However, while traveling with convoy RA 64, Harris encountered a hurricane. "I had never been so horrified in my life at the state of the seas," Harris recounted. "I never thought that a ship could do so many gyrations and convulsions. There was one moment when I was sure that we were going all the way over, as we rolled at least 45 degrees. The waves were absolutely terrific, and you saw these things coming towards you. I was not a sailor and to see it without navigational knowledge frightened the life out of me. Had we gone any further, we would have fallen over, filled with water and sunk. But luckily the ship rolled up and over. The hurricane lasted for about 12 hours from start to finish, but the height of the storm took about an hour."

Being an observer, Harris flew in the back seat of an aircraft looking at a screen for signs of U-boats on the surface. If any were spotted, the aircraft closed up and dropped depth charges. But usually by the time it reached the marked area the submarine had submerged. However, sometimes the water was so clear, that it was still possible to see meters under and discern a German boat.

"During all four trips we managed to avoid U-boats. The very fact that I am here suggests it. However, I remember seeing another escort suddenly hit by a torpedo. It killed people onboard. The ship quickly disappeared in the water," Duncan says.

Even having witnessed horrible things, by the end of the day Harris was usually so exhausted that he would fall asleep as soon as his head touched the pillow. The entire journey was too serious for entertainment or humor. Everyone's only hope was to reach the shore safely. Writing letters did not serve much purpose because when one wrote a letter on the way out, it would not be posted until his return — assuming that he made it back. But in ports, both in Murmansk and back home, there were concerts organized for the convoy.

Harris in uniform at Air Navigation School in Arbroath, Scotland, in 1943.

"We particularly enjoyed a concert that was given in our hangar on a makeshift stage by a Russian Army singing and dancing troupe. They were very good," Harris said.

Surprisingly, during the convoy's four- to five-day stays in Murmansk before setting off back, there was no contact with the Russians. People who were saving each other's lives did not communicate.

Harris recalls being very bored during stopovers in Murmansk. The convoy was not allowed to sail all the way up to Murmansk, and instead anchored at a small village about halfway down the Kola Inlet.

"The Russians at that time were very surly," Harris said. "They were under communist rule, and anyone who was seeing talking to an Englishman or a Scotsman was immediately under suspicion. That's why they kept away from us. The language was a great difficulty too. I never came across any English or American sailors who could speak Russian."

The journeys back to Britain were just as dangerous, but the difference was one of morale. They were heading home and were all set for a bit of leave. The first port of call in Britain was Scapa Flow, after which the convoy sailed down into the Firth of Clyde near Glasgow on the western coast of Scotland. There, they tied up to a buoy in Greenock and were finally ready for a short break.

As soon as Duncan reached Greenock, he would jump off the boat to get to the train station to go "hell-for-leather" up the line to Glasgow to meet his wife, Mary, who served in the WRNS — the Women's Royal Naval Service — during the war.

The last day of the RA 66 voyage was different — it coincided with the end of World War II in Europe. During the journey back, the convoy did not know that the war would end that suddenly, so for them it was just another return. It was only when they got to Britain that they learned that the war was over. They celebrated in Scapa Flow, firing a multitude of rockets that were no longer needed.

Being safely back with the family and getting on with life was a privilege that most people had dreamt of for years and one that many did not have a chance to experience. What the convoy sailors did not know was that, having risked their lives in the Arctic, their heroism would soon be forgotten.

"It took 70 years for us to become recognized," Harris said. "A few years ago was the first time I marched in the Cenotaph parade — I did that three times, but then got too old."

An older Harris stands in a Murmansk square on a return visit in 2005.

While Harris recently received a decoration called "The Arctic Star" from the British government, prior to that he had only Russian medals for his Arctic service. "They were very good with their medals," Harris said of the Russians "We received the medals but could not wear them. It was only in recent times that the British government have allowed us to declare our war service with our medals."

Harris was mystified as to why it took so long for Arctic Convoy veterans to be recognized, though he surmised that it was in part because "over this period, Russia was in the grip of Soviet rule, so relations between the two countries were bad. Anything that the Russians wanted to do, the British government was against. The Allies' help to each other was forgotten shortly after the war."

In 2005, Harris went back to Russia with another 200 Arctic Convoy veterans. They visited Murmansk and Arkhangelsk to see the places where they had stayed decades before. As expected, everything looked completely different. During the war, the old wooden Murmansk was completely burnt down, and the area appeared absolutely flat except for the brick-built chimneys. It had to be completely rebuilt afterwards. From this journey, Harris brought back an album and memories of a warm reception by the Russians. This time they were not afraid to talk to British warriors.

Having told me his story, Harris is sitting in his armchair, thoughtful. There is a photo of Mary standing on his desk — a beautiful smiling young woman with large expressive eyes. How strange and poignant this mixture of happiness, long-term danger and separation must have felt for them and all the others. How difficult it is for me to imagine.

"How did you meet Mary?" I ask.

"We first met on the first Monday of June in 1939," Harris said. "Having passed my civil service exam I was sent to London where I had never in my life been before. I was put in an enormous office with clerks clicking away and there sitting opposite me was this gorgeous girl, and that was Mary. That is how it all started. We were in touch all that time. She was in Glasgow and I did my navigational training in Arbroath. Every weekend I used to hop across to Glasgow to see her. In 1943, we got married, and shortly after I was sent away with the Arctic Convoys. We were separated, but so were millions of other people in the war. We didn't think of it as a particularly beautiful story. We just thought we were damn lucky," Duncan replies reflectively.

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.