In the late 1980s, I closely followed U.S. President Ronald Reagan's "Star Wars" program, or Strategic Defense Initiative. But what I couldn't understand was why the Kremlin took it so seriously, when the program had not developed any new weapons systems and posed no threat to the Soviet Union's national security. The answer was apparently that the Soviet military-industrial complex desperately needed a bogeyman with which it could convince leaders to allocate huge sums of money for defense, even in a rapidly deteriorating economic situation. As a result, the attempt to oppose the Strategic Defense Initiative played a significant role in the collapse of the Soviet Union. History is repeating itself as U.S. Prompt Global Strike is replacing "Star Wars" as the new bogeyman.

The Soviets believed the U.S. "Star Wars" program would upset the balance of power between Washington and Moscow. Now they are saying the same about Prompt Global Strike.

Prompt Global Strike is a conventional weapon system that uses strategic delivery vehicles, such as ballistic missiles and bombers, but with non-nuclear warheads. The Kremlin is afraid that a Prompt Global Strike attack would enable Washington to disarm Russia's nuclear forces and command centers without having to worry about a counterstrike. At a recent meeting devoted to modernizing Russia's aerospace defenses, President Vladimir Putin said, "There has been increasing talk among military analysts about the theoretical possibility of a first disarming, disabling strike, even against nuclear powers." The top brass have apparently convinced Putin that the proper response to the Prompt Global Strike threat is to build up Russia's aerospace defenses.

But does Prompt Global Strike pose a threat to Russia? In terms of the strategic balance between the U.S. and Russia, Prompt Global Strike is more likely to reduce U.S. military potential than increase it. After all, the New START treaty limits the number of strategic delivery vehicles, and each side has the choice of whether to mount nuclear or conventional warheads on them. Of course, a nuclear warhead will cause much more damage than a conventional one. What's more, the New START treaty permits the U.S. to have almost twice as many delivery vehicles as Russia — a fact that, for some reason, does not disturb the Kremlin in the same way that it frets over the U.S. missile defense system and Prompt Global Strike. But the concept of a Prompt Global Strike — using strategic delivery vehicles to carry conventional weapons — does not constitute a violation of strategic stability.

Notably, Putin spoke about countering the Prompt Global Strike within the context of creating an aerospace defense system. This implies that Putin's top military advisers have convinced him that Russia needs to develop an advanced missile defense system to destroy strategic delivery vehicles that may be fitted with conventional warheads. Putting aside for now the question of whether Russia will even manage to create this kind of missile defense system, the issue is why Moscow accuses the U.S. of attempting to upset strategic stability with its global missile defense system when Russia is itself planning to create its own version of a missile defense system.

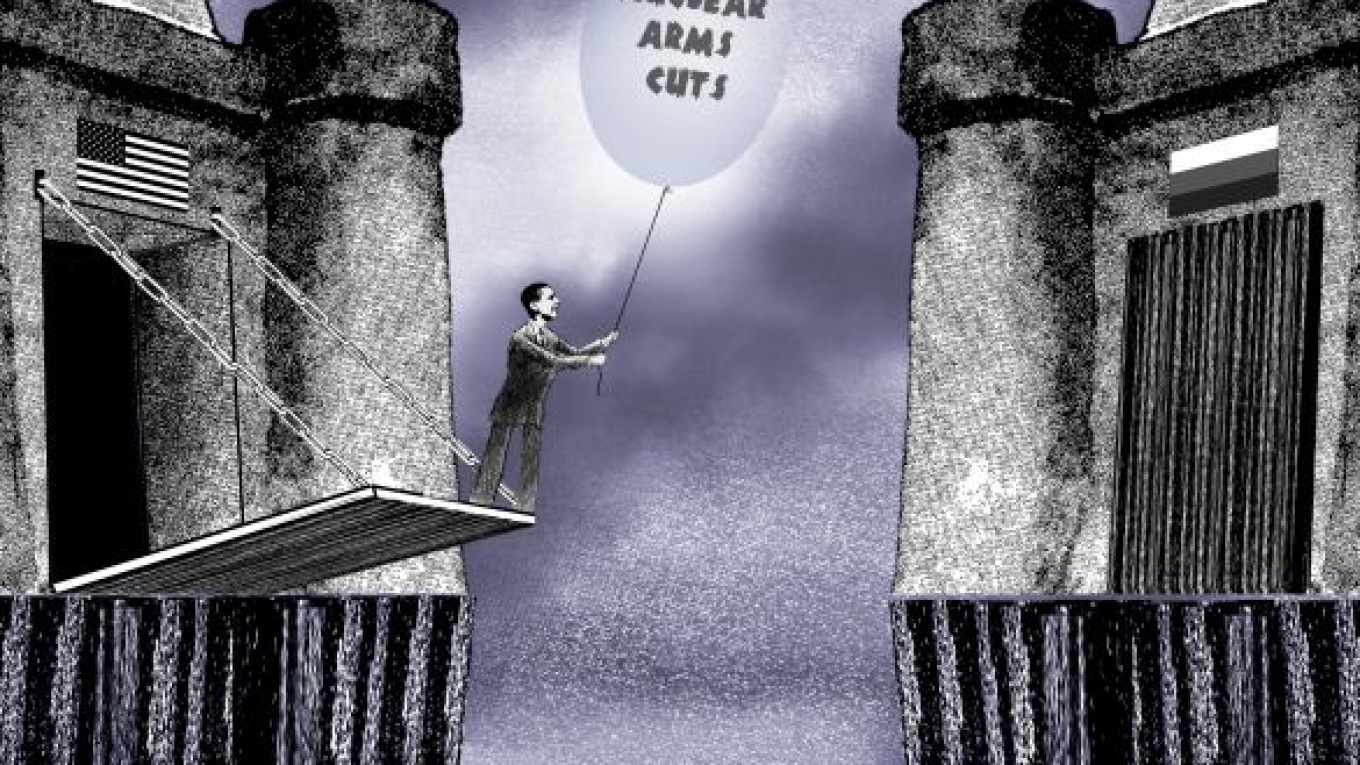

All of this coincided with U.S. President Barack Obama's proposal to reduce U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals to about 1,000 deployed warheads each, or one-third less than levels permitted by the New START treaty. Obama added a number of interesting points on U.S. nuclear strategy to his initiative. For example, Obama states that a massive disarming nuclear strike — the type Putin fears the most — is highly unlikely in the 21st century. Obama also instructed the Pentagon to drastically reduce its reliance on nuclear retaliation in strategic planning and to reduce the importance of nuclear weapons in U.S. military strategy.

In essence, Obama is once again proposing a departure from the outdated, Cold War-era concepts of nuclear deterrence, parity and mutually assured destruction.

If Russia were to agree to Obama's proposal to reduce its strategic nuclear arsenal to about 1,000 deployed warheads, it would also have to give up plans to deploy new strategic weapons systems that have not yet been built, especially heavy missiles.

Meanwhile, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov was quick to explain that Washington would have to first quell Moscow's concerns over its missile defense plans and its Prompt Global Strike system, as well as reduce the imbalance in conventional weapons in general. Only then would Moscow be ready to enter into negotiations — and only on a multilateral basis, with the participation of other nuclear countries, namely China. In reality, when Lavrov throws unrealistic demands about U.S. conventional and nuclear weapons and missile defense all into one big basket, this shows that Moscow is once again playing the spoiler role and has no interest in holding serious talks on disarmament.

The problem is that after the U.S. withdraws its troops from Afghanistan in 2014, the control and reduction of nuclear weapons is the only issue that Washington will have any real interest in discussing with Moscow. But Russia seems to have closed the door on such talks long before they even had a chance to begin.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.