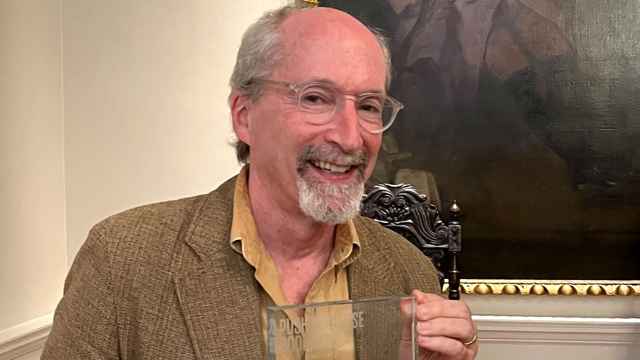

Georg Genoux found himself in an unusual position Friday night at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art on Gogolevsky Bulvar. The director, who usually works behind the scenes, sat in front of a table and, protected only by a striped scarf wrapped around his neck, bared at least part of his soul to an audience that gathered to hear him talk about the German artist Joseph Beuys and his own, now defunct, Joseph Beuys Theater in Moscow.

Genoux came to Russia from Germany in 1997 and has been one of the most interesting, probing and honest theater-makers in this city since the early 2000s. In recent years, he plied his vision of theater and social activism at Teatr.doc, the Playwright and Director Center, the Joseph Beuys Theater, the Sakharov Center, the Memorial historical and civil rights organization, and a cultural center in the Moscow region town of Zhukovskoye. He staged productions in several Russian cities, including Saratov and Voronezh. He played one of the lead roles in Pyotr Todorovsky's 2003 film "In the Constellation of Taurus," a film about the Battle of Stalingrad.

Point made: Georg Genoux has been busy and productive in Russia. He has, however, made the decision to return home to Germany, leaving behind most of his Russian accomplishments. That, in part, is why he agreed to speak at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art — yes he did it to help kick off a new exhibit of works by Joseph Beuys, but he also did it to say why he felt it necessary now to strike out in a new direction.

I have one or two personal reasons to be grateful to Genoux, but they are so insignificant they don't require repeating. I mention this only as a nod to those who might want to question my reasons for some words of praise that may follow. Suspect me of being excessively subjective if you will, but don't doubt the magnitude of Genoux's contributions to Russian theater of the early 21st century.

Talking on Friday, Genoux admitted that he probably would have left Russia in the early 2000s had he not come into contact with Teatr.doc, a theater founded in 2002 that worked primarily with documentary materials drawn by writers and directors from real life. He said he felt alone and misunderstood in the directing class of Mark Zakharov at the Russian Academy of Theater Arts.

"I came to Moscow in 1997/1998 at a time when Moscow theater was more interested in theater as entertainment than in theater as a spiritual endeavor," he said. "I studied with people who weren't interested in what I was interested in."

Teatr.doc "had a collective process and I felt good there," he declared.

Genoux's belief in theater as a place of collective activity and healing goes back to his early studies of the philosopher Rudolf Steiner and the influence of his parents, both artists and students of the prominent German artist Joseph Beuys. Students of Beuys, just like students of Genoux's parents at their own Free School of Arts in Hamburg, determine their own curriculum of study. It is an approach that suggests people learn best when they are pursuing their own goals. It is an approach that Genoux fashioned into an artistic approach.

When seeking partners for projects at various venues, Genoux said during his talk, "I looked for people who had projects, without which they could not live."

He looked for ways that would force audiences to consider the world around them. His production of "Democracy.doc" at Teatr.doc was an interactive work where the spectators themselves decided what characters needed to be on stage and then selected the performers for those roles from among their own ranks. The result was a strange and affecting happening in which individuals playing the roles of "government," "police," "opposition," "terrorist" and many others, moved clumsily around the stage and engaged in polemics that arose spontaneously.

Genoux explored his own German heritage in a way that provoked Russians to consider their own.

His production of "Anne, Helga and I" was a brief but powerful look at the parallel fates of three individuals — Anne Frank, Helga Goebbels and Georg Genoux. The director used this tale about two teenage girls who were destroyed by history and politics run amuck to focus on a paradox in his own family's past. One of Genoux's biological grandfathers was a member of the Nazi secret police. The man he knew as his grandfather until he was 17 was a humanist, a translator of the works of Anton Chekhov.

Another of Genoux's projects, "The Burden of Silence" directed by journalist Mikhail Kaluzhsky, explored the lives of children of Nazi criminals. It was always followed by a discussion moderated by Kaluzhsky.

"Curiously enough," Genoux stated on Friday, "Russian spectators always turned the discussion into a discussion of life in the Soviet Union."

I can see Genoux's soft smile in the words "curiously enough." There was, of course, nothing "curious" about it. This was precisely his goal — to provoke people to think and talk.

Answering his own rhetorically posed question as to why he, a German, began making politically charged theater in Russia, Genoux declared that one of Joseph Beuys' key notions for healing the world was to "bring the East and West together."

Georg Genoux had a profound influence on me. Perhaps because I am a highly politicized individual, I have always sought to keep my politics and theater separate. Art, it has seemed to me for most of my adult life, has purer, cleaner, higher strivings. It is a place for eternal truths, not daily battles. This is what I believed for many years, even decades, and it is what I believed when I first encountered Georg Genoux's art.

I did not like his work at first. I was, in fact, called to play "the government" in his "Democracy.doc," and I was horrified. I went home that night a man of two minds. I was dismissive of what I had experienced "as theater," and I was moved by the socio-political experiment I had experienced. Rejecting "Democracy.doc" on one level, I was fascinated by it on another.

In time I began attending many of the Genoux-inspired projects at the Joseph Beuys Theater, which usually worked in various spaces at the Andrei Sakharov Center. These were often one-off discussions, happenings or pseudo-performances that blurred the boundaries between theater, sociology and politics. As a rule I was skeptical of them going in. I usually left the Sakharov Center still conflicted, but always inspired and impressed.

Was I perceiving art or was I reacting to socio-political stimuli? The change in my own mind occurred when I realized that my question was irrelevant. These events were what they were. They were real and they were of their own genre. They had a clear-cut goal — to shake people out of their ruts — and they succeeded. It didn't matter one whit what you called them. They were powerful, they were thought-provoking, they had substance and they reflected on, and responded to, the world that was coming into being around us in the Putin-Medvedev-Putin era.

They invariably used theatrical means to drive their message home. Who am I to say they were not theater?

The most recent project Genoux took part in occurred in Berlin under the general title of "Crisis." He was asked to present something on the topic and, as he tells it, everyone expected him to shed light on current events in Russia — the Magnitsky case, the Politkovskaya murder, Putin's presidency. Instead he organized an evening in which he talked about crises of personal direction and then, as Genoux would do, began involving audience members to share their own experience with personal crisis.

This crisis has led the director to wrap up his activities at the Joseph Beuys Theater and head back to his homeland to recharge his batteries. He does not count out the possibility that he may return to Moscow some day in a new capacity, but if he does it will not be to resurrect the past.

Here is how he put it in his own words on Friday: "I wasn't able to create a place where people of various backgrounds and professions could come and realize their projects, maybe even come and say 'I'm in crisis and I need money and a team to help me out of it.' It didn't happen. And then I began to think, maybe I shouldn't be trying to force it."

Georg Genoux knows best where he succeeded and where he failed. I wouldn't have an opinion on that. I will say this: If theater and the public discourse that surrounds it are more open, more grounded in reality, more inquisitive and more demanding than they were a decade ago, Genoux can take credit for being one of those individuals who fostered that change.

That's not success we're talking about, that's substance.

Fortunately, there are a few Genoux projects still on tap. The Joseph Beuys Theater production of "Uzbek" continues to play in the exhibition hall at the Sakharov Center. And "The Man Who Didn't Work. The Trial of Joseph Brodsky," a documentary performance that grew out of a workshop Genoux led at the Memorial Society, will still play from time to time.

As nice as it may be still to have these few events around, the only real conclusion to all this is clear: Moscow will be a poorer place without Georg Genoux.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.