Fashion-conscious Soviets loved Pani Walewska perfume and Miltons jeans, while the oligarch decade ushered in Bentley cars and Dior stiletto heels. But these days, all you need to be hip in Russia is a white ribbon and a little anger.

Protesting for free and fair elections has consigned the bling thing to the vintage bin of history, for now, ahead of the March 4 presidential election, which is widely expected to be won by former President and current Prime Minister Vladimir Putin.

"All go to these protests. I have no doubt that it is the newest trend," said Alexander Arutyunov, a Russian fashion designer, who started a blog "Fashion on the Barricades" after the latest protests on Feb. 4 that had an estimated crowd of about 80,000 people.

"It is an unexpected trend, I had no idea so many people, so many well-known people — celebrities, actors — would go to these demonstrations, but it has become a trend."

The recent opposition protests, the largest since the early 1990s, have been very much about serious politics and the demand for democracy. But somewhere along the way fashion began to play a role, and now it threatens to help divide the country further.

White ribbons — a symbol used by the opposition — can be found everywhere on Moscow's streets from student backpacks to posh people's purses, signaling widespread sympathy.

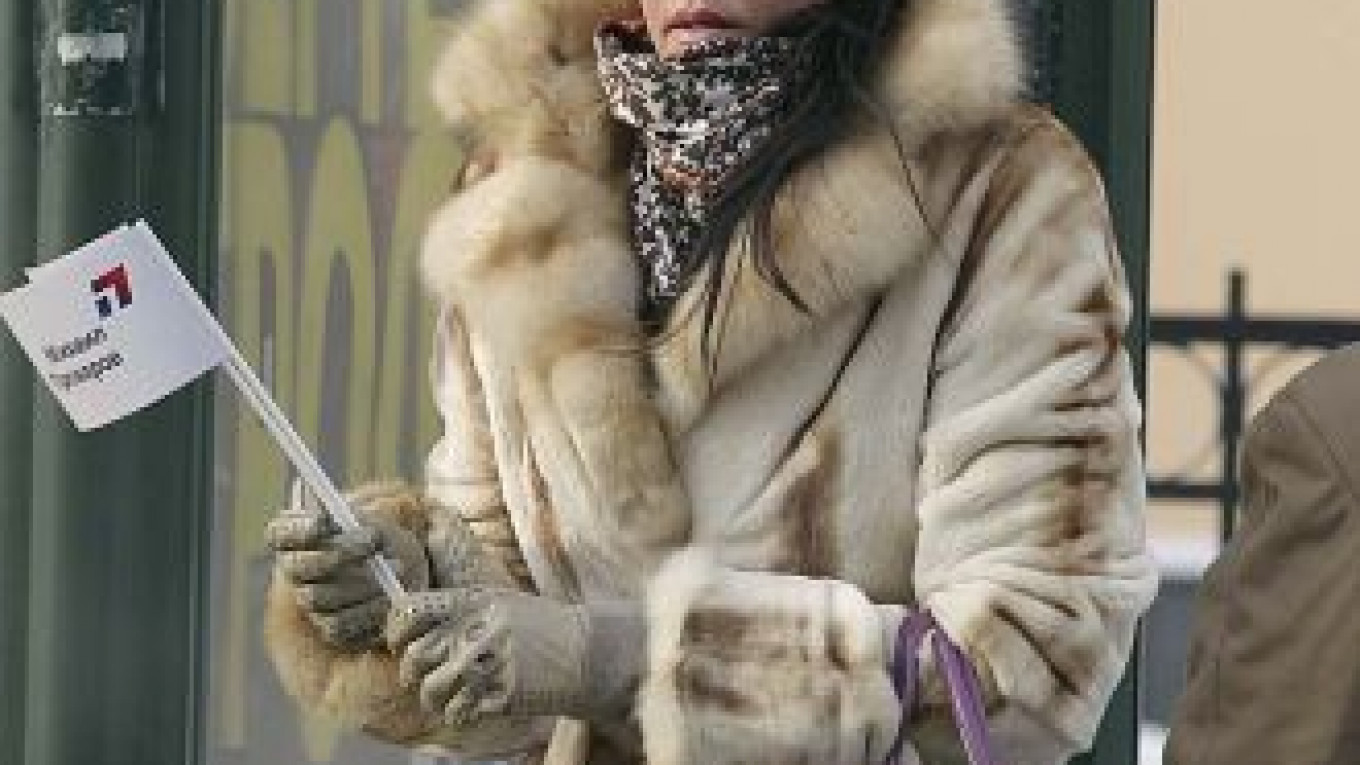

Then, there is the issue of fashion, increasingly used by officials as a tool to divide society between the poor in battered quilted jackets and the rich in mink coats.

"The most despicable thing the authorities do — they split people into two camps," tweeted Russian socialite and reality TV host Ksenia Sobchak.

The growing opposition movement has been supported largely by an emancipated middle class. Despite owing their economic and social rise to Putin's leadership, this section of Russian society still demands greater rights and freedom.

Officials from Putin's United Russia ruling party have been trying to downplay the opposition, suggesting the protests are limited to a group of rich and bored liberal urbanites.

"It's a lie," left-wing leader Sergei Udaltsov told a protest crowd on Feb. 4. "We are not revolutionaries in mink coats."

The New York Times reported that somebody in the crowd at that point shouted "I am." Udaltsov continued, "I've been wearing this jacket for three years and you (the ruling elite) have villas."

On his blog Arutyunov, who says his interest is not in politics, but fashion, champions the idea that people who attend the protests should dress better.

"If you decide … to go to the protests — dress up! Make it a statement. Have some fun with it," he wrote.

He wore high-platformed Prada shoes and a jacket and trousers of his own design. But his favorite look was a slim girl wearing a sheepskin coat, a traditional Russian scarf on her head, teamed with green sunglasses and bright red lipstick.

"Very Russian and very stylish," he wrote on his blog at Fashionprotest.ru.

Sobchak, the high-society daughter of Putin's late friend and former St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak, is a critic of Putin.

Russia's answer to U.S. socialite Paris Hilton advises protesters to leave displays of wealth, such as mink coats, at home when attending demonstrations that so far have all taken place in frigid weather.

"I wear a down [jacket]," Sobchak said.

During recent demonstrations, posters that read: "I'm ready to dress less well" showed fashion was as much a part of the political battleground as opinion polls and sound bites.

The placards were a riposte to a YouTube video in which a member of the pro-Kremlin Nashi youth movement lists the fact that people can now dress better as one of the achievements of Russian President Dmitry Medvedev's term in office.

While the protests have been peaceful and playful, they also provide a public activity where people can enjoy themselves and feel proud.

"Now, suddenly, a civic stance has become fashionable," Georgy Alburov — who runs RosVybory, a new project by Alexei Navalny, a blogger and the main engine behind the protests, aimed at monitoring the presidential election.

"It has become trendy to go to demonstrations. When a person who hasn't gone to the protests gets asked what did you do on Saturday, he needs to justify why."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.