The Tretyakov Gallery is now showing a grand retrospective devoted to Nikolai Ge, a 19th-century Russian artist of French descent, whose work was rejected by the artistic establishment and who is now seen as a prototype of Russian expressionism.

Ge spent his life in search of spiritual understanding and artistic acceptance, and despite critical reviews, including the disapproval of Tsar Alexander III, he never abandoned his search to find an artistic style and spiritual understanding with which he felt comfortable.

This is reflected in the title of the Tretyakov exhibit “What Is Truth?” a tribute to Ge’s journey to find answers to what the gallery calls the “eternal questions.”

“The Russian people were not ready for the kinds of provocative symbolism with which Ge presented them,” said Tatyana Gorodkova, the exhibit’s curator.

Arranged into six chronological sections, the exhibit follows Ge’s long career from his conventional academic beginnings in the 1850s to travels to Italy, St. Petersburg, the Ukrainian countryside and the final periods influenced by Lev Tolstoy and ending in his last great series of biblical paintings known as the “Passion” series in the 1890s. The different sections show the changes in Ge’s style and how he looked for acceptance among his contemporaries.

“Only later on in his life, after he no longer needs to pay attention to society’s opinion, does Ge return to his earlier style,” Gorodkova said.

In 1857, Ge begin his journey away from the Academy of Art style, traveling to Italy in search of “air and freedom.” However, the creative growth that Ge underwent while abroad was not positively received upon his return to Russia.

“Heralds of the Revelation,” painted in 1867, received criticism upon its unveiling in Russia. Italian stylistics were considered “primitive” in comparison with the realist paintings popular among Ge’s contemporaries, and Ge’s wall-sized depiction of Mary Magdalene after Christ’s resurrection received further criticism upon its unveiling in Russia.

Upon his return to Petersburg in 1870, Ge directed his attention to historical subjects and portraits in hopes of receiving acceptance in Russian art circles. Most striking among the historical paintings is “Peter the Great Interrogating the Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich.” The canvas conveys the tension between Peter and Alexei, while still acknowledging the poignancy of a father and son at odds.

A display of Ge’s portraits from this period is largely comprised of Petersburg intelligentsia who accepted the artist into their circle, finding him to be an intellectual equal. However, after five years in Petersburg, Ge became increasingly discontent with the concept of art as a business, and moved to a farm settlement in Ukraine. His landscapes from this period convey a sense of peace in the countryside and bear a resemblance to those from the artist’s time in Italy.

However, it was not until Ge read about Lev Tolstoy in the early 1880s, that the painter truly found peace with his surroundings. In his memoirs, Ge wrote that the great writer’s philosophy, based on ascetic morality with roots in early Christian teaching, allowed him to forge a path to better understand his relationship to the world and to his art.

“Everything became clear to me,” Ge wrote. “Art was pulled down by the fact that everything was disproportionally higher than it.” Ge became close friends with Tolstoy and painted a famous portrait of the writer in 1884.

This understanding brought Ge “endless happiness,” and 12 years after the beginning of Ge’s transformative relationship with Tolstoy, the artist began his last project before his death in 1894: the “Passion” series.

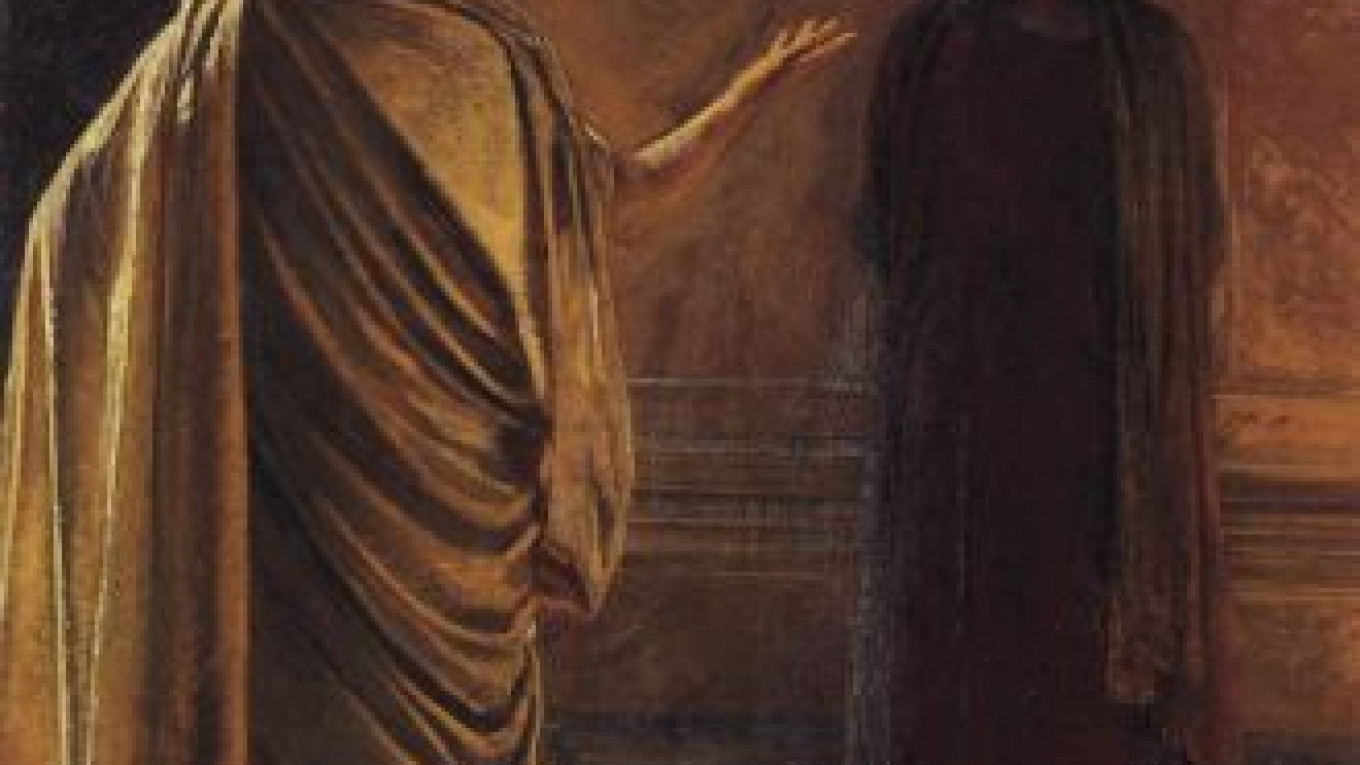

This group of paintings depicts Christ’s betrayal, interrogation and crucifixion. The painting, “Quod Est Veritas? Christ and Pilate,” in which Christ is interrogated by the Roman leader, was expelled from а Wanderers exhibition in 1890 as it was seen as a critique of excess in modern society.

Despite the fact that his last works were not welcomed into Russian art circles, the paintings proclaim Ge’s ultimate personal success in finding truth outside of societal dictates.

To emphasize the idea of discovery, there is a separate section of the exhibit devoted to examining the layers of several of Ge’s works. This part of the exhibit includes large displays of Ge’s paintings that he reformatted, a touch-screen that allows the user to find out more about how and what Ge modified on selected canvases, as well as a video about the restoration and preservation of the artist’s paintings.

Included on this lofted floor are display cases of Ge family artifacts, including letters and photographs, to provide another layer of context for understanding Ge.

“What Is Truth? Nikolai Ge, 180th Anniversary,” runs at the New Tretyakov Gallery until Feb. 5. Audio guides in English are available. 10 Ulitsa Krymsky Val. Metro Park Kultury.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.