It has been two years since the European Union launched its Eastern Partnership in 2009. The Eastern Partnership was conceived before the war, but its implementation was subsequently accelerated to reassure Georgia and its nervous neighbors that the EU opposed any effort by Russia to impose a "sphere of influence" on the region.

But the Eastern Partnership has only a small budget for mainly technical projects, and it has done little to beef up the EU's pulling power in the East. The only significant European leader to attend the Eastern Partnership's initiation in Prague in May 2009 was German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

The EU could do with more friends, but the Eastern Partnership is still struggling to find a success story. Belarus, always an outlier, has lurched from post-election political crisis in December 2010 to economic crisis this summer. Not so long ago, Ukraine was hoping to sign a new association agreement and a deep and comprehensive free-trade agreement at an EU-Ukraine summit in December. But those accords are in jeopardy now that former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko has been sentenced to prison on what appear to be blatantly political grounds.

Farther east, the threat of renewed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh is higher than in many years, and Georgia itself initially stood aloof from the Eastern Partnership. Since its "Rose Revolution" in 2003, the country has cultivated an image as an ultraliberal dynamo, with officials attacking the EU for its "sclerotic civilization" and the International Monetary Fund as "Gosplan on the Potomac."

This was not mere rhetoric. When institutions proved difficult to reform, the Georgians often simply abolished them — most famously the traffic police and even the local Food Standards Agency. And real progress was made in cutting corruption: Less than 5 percent of Georgians reported making "irregular payments," according to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development's 2011 "Life in Transition" survey.

But the boom years of 2004-08, with growth topping 12 percent in 2007, seem over. Inward foreign direct investment in 2010 stood at $553.1 million (4.7 percent of gross domestic product), down sharply from the record of $2 billion in 2007 (19 percent of GDP). The Russian market has collapsed, owing to Russia's "health and safety" bans on Georgian imports. Turkish imports dominate local food markets, despite the historic reputation of fertile Georgia's wine, fruit and mineral water.

The EU might help to bring foreign investment back. The Georgian government's sudden Euro-enthusiasm is also driven by the collapse of its NATO aspirations after 2008, together with U.S. President Barack Obama's "reset" policy toward Russia, which is much resented in a country where the road from the airport into Tbilisi, the capital, is called "George W. Bush Avenue." Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili has toned down his rhetoric about Georgia following a "Singaporean model." He still talks of a low-tax, low-regulation future but justifies the Singapore metaphor in geopolitical terms. Georgia, too, he argues, is a regional hub with overbearing neighbors and a dynamic economy built on a cosmopolitan base.

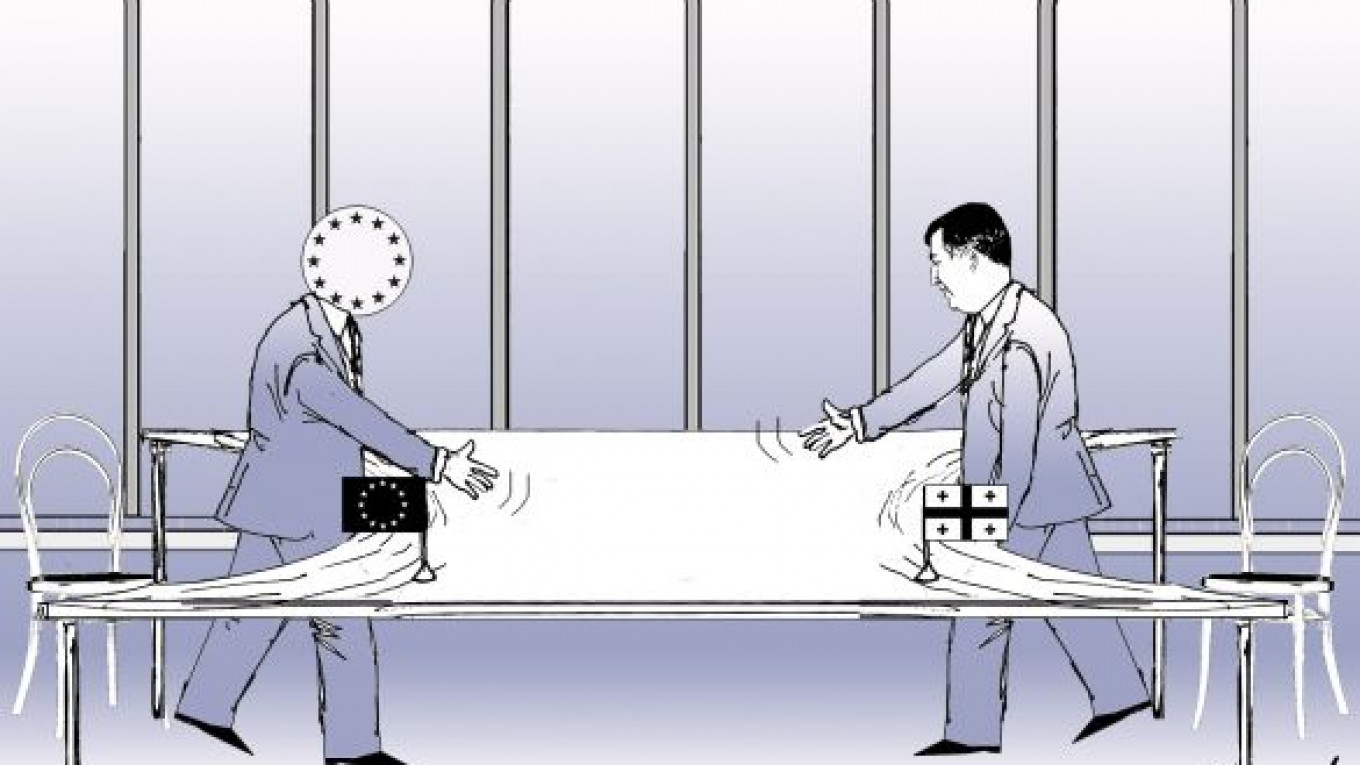

Georgia would be an ironic success story, but the EU seems likely to announce the country's readiness to be fast-tracked toward a free-trade agreement after 2 1/2 years of often painful "pre-negotiations." Closer relations with the EU also mean political parameters. Georgia has duly liberalized its civil code on ethnic and religious minorities, despite fierce opposition from the Georgian Orthodox Church.

But the political scene remains bitterly divided between an entrenched ruling elite with a reputation for cutting corners and a weak and divided opposition, whose maximalist wing has marginalized itself by constantly campaigning for Saakashvili's resignation. Five days of demonstrations in Tbilisi in May seemed deliberately designed to provoke violence. The government didn't cover itself in glory by sending in the riot police, although the two demonstrators who were killed seem to have been struck down by an opposition leader's fleeing car.

Presidential elections are due in January 2013, when Saakashvili's second and final term is up. Saakashvili denies that he will copy Prime Minister Vladimir Putin by moving to the job of prime minister, which would actually be "Putin-plus," as the constitution was amended in October 2010 to shift power to the prime minister. But he is young at 43, and his mission to recover the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia is still unaccomplished.

Georgia still argues that it can have the best of both worlds: a better relationship with the EU while maintaining the vibrancy that makes it unique. It claims, for example, that it can adopt the free-trade agreement while adding only minimally to domestic business costs. It has also sought to reassure foreign investors that its libertarian heart still beats. In July, the government enacted a "Law on Economic Freedom," which makes any new state tax subject to referendum and introduces legally binding macroeconomic parameters to keep the budget deficit below 3 percent of GDP, total state debt below 60 percent of GDP and government expenditure below 30 percent of GDP. Fiscal discipline, it seems, is not just confined to Europe's north.

It should also be borne in mind that the desire to regain influence over Abkhazia and South Ossetia is driving Georgia's new embrace of the EU. With NATO membership no longer an immediate prospect, Giorgi Bokeria, the head of the National Security Council, has called on the EU to play more of a hard military role in the region, transforming its monitoring mission in Georgia into something more like its peacekeeping force in Bosnia.

Georgia will test the EU's new flexibility in the East. The country is ahead of its neighbors in many areas, but behind in others, including national security. But the political will, on both sides, for closer cooperation appears to have emerged at last.

Andrew Wilson is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.