Tatyana Karpova sits on a patched leather couch in her musty ninth-floor apartment in southeastern Moscow, her wrinkled hands folded on her lap. A worn rug hangs on the wall above her head. The decor dates back to a happier time, before the night of Oct. 23, 2002, when her son Alexander set off to a local theater to see the Russian musical "Nord-Ost."

Alexander was among the 130 people who died after Chechen terrorists took about 900 people hostage for three days at the theater in Moscow's Dubrovka neighborhood, prompting the intervention of Russian special forces.

Twelve years later, Karpova is still waiting for clarity and closure. The 68-year-old is waiting for Russian authorities to acknowledge their mistakes during the three days of the tense siege.

Twelve years ago, Chechen terrorists took more than 900 people hostage at a theater in Moscow's Dubrovka neighborhood, forcing Russian special forces to intervene. Tatyana Karpova's son Alexander was among the 130 people who perished as a result of the three-day siege.

In 2011, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Russia had violated the hostages' basic right to life during the rescue operation, in which a mystery knockout gas was pumped into the theater. Although some Russian politicians have admitted that the country was unprepared to handle the crisis, authorities have refused to elaborate on the rationale behind their decisions and their management of the situation.

"We received a condolence letter from the American ambassador to Russia at the time," Karpova says. She removes the letter from its frame, prominently displayed on the living room's bookcase. "We never heard anything from local or federal authorities. No condolences, nothing. "

A Night at the Theater

The artistic mind of Alexander Karpov — whom his mother affectionately refers to as Sasha — was always percolating. Sasha loved folk music, foreign languages, The Beatles and Tolkien. He was the proud father of a 4-year-old daughter. He was a born performer and songwriter, founding his own band in the mid-1990s.

In the summer of 2002, Alexander was hired to translate the American musical "Chicago" into Russian. He and his wife Svetlana — who survived the theater siege — had a pair of tickets to "Nord-Ost," which one of their friends had produced. Karpova, who works as an English tutor, says her son was keen to see the musical and compared it to "Chicago."

During the second act of "Nord-Ost," a love story set during World War II, Chechen terrorists — 22 men and 19 women who had driven 1,500 kilometers to Moscow — stormed the building. Armed gunmen took the stage.

"I thought it was some kind of mistake," says Viktoria Kruglikova, a Moscow schoolteacher who attended the show that night with her daughter, sister and 15-year-old nephew. Her nephew, Yaroslav, did not survive. "They came onto the stage so abruptly, we were all shocked. We thought it had to be some kind of misunderstanding."

The leader of the armed group, Chechen rebel Movsar Barayev, told the hostages that if Russian troops did not withdraw from Chechnya, the theater would be blown up. About 10 days before the siege, Russian forces had claimed to have killed Barayev in the North Caucasus republic.

Throughout the mid-1990s and the early 2000s, Russia waged two brutal wars in the breakaway republic of Chechnya. The majority of terrorist attacks perpetrated in Russia at that time took place in the south — including in the cities of Budyonnovsk, Pyatigorsk and Vladikavkaz — near the restive republics of the North Caucasus. Moscow had also known its share of terror, with the 1999 apartment bombings that claimed 233 lives and the deadly bombing of an underground crossing under Pushkin Square in 2000. But the capital had never witnessed anything quite like this.

The hostage-takers released a handful of children, pregnant women, Muslims and foreigners. The others were ordered to remain in their seats.

The heavily armed fighters and the large bombs they had put in the center of the auditorium posed the challenge to Russian security forces of how to disarm the terrorists without harming the hundreds of innocent people in the building.

Several hostages, mostly children, being released from the besieged theater. The rest were held for three days.

Knockout Gas

In the early hours of Oct. 26, the third day of the siege, special forces released a knockout gas into the theater's ventilation system, hoping to render both the terrorists and the audience unconscious.

"There was an odd smell in the air all of a sudden," Kruglikova says. "The tensions of the last three days seemed to slip away. We were all very sleepy."

As the gas took effect, Russian troops stormed the theater, shot the terrorists dead and began removing the unconscious hostages. Hostages were laid haphazardly on the front steps of the theater, making it nearly impossible for medical personnel on the scene to monitor who had already been treated and administer to the hostages with any kind of method.

The paramedics were not told what kind of gas had been used in the operation and were therefore unable to provide patients with a proper antidote. Nor were local hospitals warned of the arrival of the unconscious hostages.

"No one told the waiting buses where to take the people. Can you imagine?" Karpova says. "There was such a panic that the drivers were asking each other where they were supposed to take the injured hostages."

Some families did not know where their loved ones were or what had become of them for days after the operation, only to eventually track them down themselves by visiting the city's morgues. Karpova's hopes were dashed when she found her son's body in a hospital morgue.

A few days after the siege ended, Health Minister Yury Shevchenko said the gas was composed of fentanyl derivatives, a non-lethal opioid broadly used in medicine. Independent observers have said the use of fentanyl was extremely unlikely given the manner in which the hostages quickly became unconscious. To this day, authorities have not publicly identified the gas, and no one has been held accountable for the botched rescue operation.

"Could special forces have avoided storming the building? We don't know, we are not military strategists," Karpova says. "But what ordinary Russians cannot understand is how you can conduct an operation without knowing what comes next. They released the gas but didn't know how to get it out of people's systems."

In the aftermath of the siege, authorities claimed that the fatalities had occurred not as a result of the gas, but among people who had in fact succumbed to pre-existing chronic medical conditions.

"Sasha was young and healthy," Karpova says. "I was told that he died because his kidneys and liver were chronically diseased and that they had failed. There was not an ounce of truth in this. Even the children who died were listed as having had serious chronic illnesses."

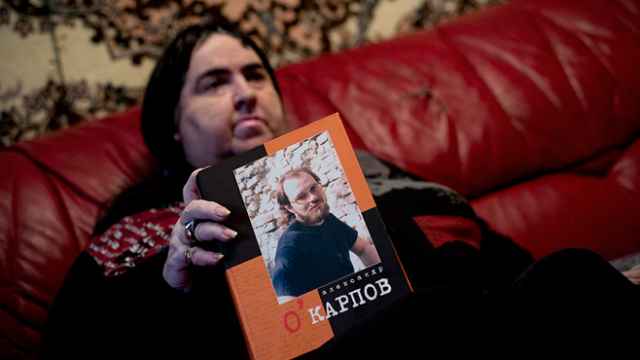

Tatyana Karpova showing reporters a book about the life of her son, a musician who died in the hostage-taking.

'Successful' Operation

Karpova spearheaded an investigation into the siege that she says found that 97 of the 130 hostages who perished, including her son, had not been given any medical assistance.

She has in her possession six official documents she says prove that Alexander was alive for more than 6 1/2 hours after the special forces' operation, but that he was put in a bus filled with corpses.

Authorities declared the operation at the theater a success. They initially said that Russian forces had killed the terrorists and that no hostages had perished in the process, according to hostages' families.

Karpova says she felt insulted to the core by the official assessment of the operation.

"How can you call an operation a 'great success' when so many people died?" she said.

Former State Duma lawmaker Gennady Gudkov, who served on the legislative body's security committee at the time of the hostage taking and went on to become critical of the Kremlin, said authorities had indeed conducted a successful operation.

"I personally consider that the operation was successful because, in itself, it did not cause a high number of casualties," Gudkov told The Moscow Times in a telephone interview. "But regrettably the subsequent rescue operation was disorderly, and this is what resulted in the deaths. Many things could have been done differently in the aftermath of that operation, from a purely organizational perspective."

Russian security analysts, who have not shied away from highlighting the shortcomings of the medical treatment given to the hostages, have said that without the intervention of the elite Alfa and Vympel anti-terrorism squads, the whole audience would almost certainly have perished.

An archive photo showing negotiators outside the theater where nearly 1,000 people were held hostage in 2002.

Never Again

Karpova's three sons — Alexander, Nikolai and Ivan — were all named after Russian tsars. After losing her eldest son in a tragedy that turned into a travesty, Karpova's attitudes toward Russia's leadership have changed.

"I will never forget and forgive [President Vladimir] Putin for what he did, but mostly for what he didn't do," she says. "How could he let a gang of heavily armed people get into the center of Moscow?"

Karpova and relatives of other hostages spent the three days of the siege inside a vocational school located down the street from the theater. They were elated when authorities initially announced that there had been no casualties, and shared their shock and grief when they learned of the 130 deaths.

"After it happened, we knew we had to stick together," Karpova says. "So we founded an organization that supports those affected by the tragedy."

Karpova co-chairs the Nord-Ost Foundation, which provides financial assistance to those affected by Dubrovka and other terror attacks, such as the 2004 Beslan school hostage-taking that left more than 300 people dead, including 186 children. Funds collected through the foundation have been used to cover the cost of victims' funerals, survivors' medical treatment and the cost of schooling for the children who were orphaned in the tragedy, Karpova said.

"We were all injured because of that gas," Kruglikova says, choking back tears. "To this day, my daughter and I have serious health issues. I have problems with my heart and liver. And it is virtually impossible to get any help from the state. We have to do everything on our own. We should not have to ask for help, it should be offered."

Kruglikova says she does not want an apology from authorities. Like Karpova, she just wants closure.

"I never want anything like this to happen again," Kruglikova says. "I just want people to be safe. That's all I want."

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.