It was a night designed to showcase the Kremlin’s vision of cultural independence from the West and show Russian viewers that efforts to isolate their nation over the invasion of Ukraine had failed.

But the Intervision Song Contest — Russia’s revival of a Soviet-era contest in response to being kicked out of Eurovision — could not escape the shadow of the much more famous European competition it sought to distinguish itself from.

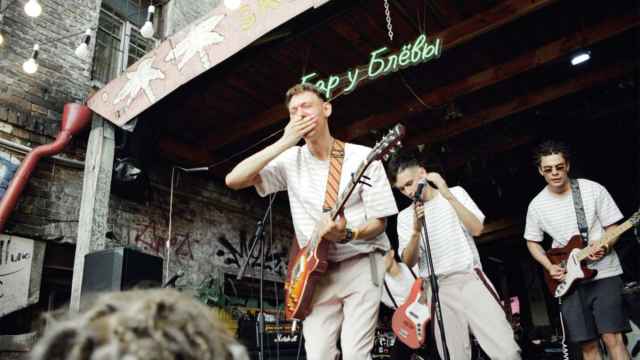

Bringing 22 musical acts from BRICS, CIS, Latin American and Middle Eastern countries to the stage at Live Arena outside Moscow, Intervision was marked by awkward moments, forced solidarity and performances that often fell flat.

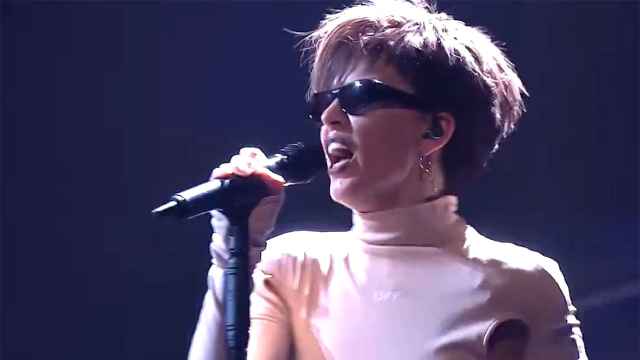

The broadcast on state-run Channel One opened with a performance from Russia’s only Eurovision winner Dima Bilan and its 2015 contestant Polina Gagarina.

What followed was four bizarre hours of Russia’s attempt to recreate Eurovision — at times looking like nearly an exact copy — interspersed with moments of performative international solidarity.

Speaking a mix of Russian, English and Chinese, the hosts hailed a “historic” night in which all contestants were united by the language of music.

But while the hosts preached unity and respect and lavished praise on each of the acts, technical hiccups and gaffes peppered the event.

Two of the hosts mispronounced “Kazakhstan” and “Kyrgyzstan,” technical difficulties delayed the jury vote and someone wandered into the Saudi judge’s shot while he was supposed to be showing his votes.

And although the hosts noted that there were billions of potential viewers, the program’s official YouTube broadcast had garnered just 103,000 views at the time of publication.

While Intervision billed itself as a “de-politicized” celebration of music, President Vladimir Putin himself appeared in a pre-recorded video address.

Standing in a windowless conference room in front of two Russian flags, he hailed international friendship, traditional values, cultural diversity and the right of every nation to “develop freely” and “preserve their identities.”

“We value our traditions and respect the traditions of others. Specifically, respect for traditional values and for cultural diversity,” he said, omitting any reference to his war on Ukraine.

Minutes later, the cameras in the arena cut to Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, who told the show’s hosts that the idea for the contest was “beautiful,” and that it was important for the contest to invite “BRICS countries and their partners.”

After an energetic performance, Russia’s representative, the pro-war pop star Shaman, asked the jury not to consider his performance for the contest’s top prize.

“I’m representing Russia, and Russia has already won. We won because everyone is here as our guest,” he said from the stage.

There was a clear attempt to play on the Russian audience’s sense of patriotism, from eventual winner Duc Phuc saying that the GUM department store had the “best ice cream in the world” to Qatar’s Dana Al Meer being presented with a traditional Russian balalaika.

After Kyrgyzstan’s NOMAD Trio left the stage, the broadcast cut to an interview with Uzbek artist Shokhrukh Ganiev and his mother. Ganiev told the hosts that while it was his first time in Moscow, his mother was last there in 1979. He continued that he was excited for his mother to see Red Square again and that he had “fallen in love” with it.

Following Chinese artist Wang Xi’s performance, one of the hosts noted how “cool” it was that Russians could now go to his concerts without a visa, referencing a new agreement between Russia and China.

In perhaps the most political moment of the evening, the organizers announced that the U.S. contestant, the Australian-born singer Vassy, had had to withdraw at the last minute due to what they claimed was “unprecedented political pressure from the Australian government.”

As the competition drew to a close, one of the hosts called Intervision “a new trend in the world of music” before announcing that next year’s show would take place in Saudi Arabia.

After Duc Phuc of Vietnam was pronounced the winner, all 22 acts performed a joint number titled “A Million Voices.” While the ballad was an overly saccharine multi-lingual revision of Polina Gagarina’s controversial 2015 Eurovision song “A Million Voices,” it was undoubtedly the most authentic-feeling moment of the evening.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.