“The world around you collapsed in a second and suddenly everything became unsafe — like you wake up one morning and they tell you that you’re now a second-class citizen,” one queer woman from St. Petersburg told The Moscow Times.

Since Russia’s Supreme Court declared the so-called “international LGBT movement” extremist one-and-a-half years ago despite no such formal movement existing, the country’s queer community has been subjected to growing pressure, fear and repression.

Under this sweeping designation, any public display of queerness — a rainbow badge, a photo with a same-sex partner, even a book — can be interpreted as extremist.

“I hide my orientation, but hiding has become part of me. I’m used to it,” said a 24-year-old gay man from Moscow. Like all queer people who gave comments for this story, he spoke on condition of anonymity.

All of the queer people who spoke to The Moscow Times said that the main problem is that the boundaries of what counts as illegal under the extremism declaration remain unclear, prompting many queer people to hide their sexuality altogether.

“I’m in a relationship, but outside of our [social messenger] chats and our home we’re just friends,” one gay man said, describing how many queer people live in Russia.

“You don’t know what’s allowed, what’s forbidden or what punishment you might face,” said the queer woman, 34, from St. Petersburg.

“Will you go to prison for 10 years over a picture on [social media VKontakte]? Or just get fined for rainbow earrings? Or will someone harass you on the street for holding hands with your girlfriend? You don’t know,” she questioned.

Another gay person said he feels that “there’s no place for people like me” in Russia.

“I don’t feel safe — even going to a gay club could cost me my job or worse. Holding hands with a boyfriend could mean jail or death in jail. I have to force myself to adapt to a society that has no space for me,” he said, referring to widespread reports of abuse and harassment against LGBTQ+ people in Russian prisons.

In 2024, Russian courts handed down 146 fines for so-called “gay propaganda,” an offense first introduced in a 2013 law that has been expanded over the years.

Since the extremist designation, Russian authorities have opened at least 12 criminal cases on charges related to LGBTQ+ activities, according to the independent rights watchdog OVD-Info. These charges are punishable by up to 12 years in prison.

One of the most tragic cases in the wave of prosecutions for “LGBT extremism” is that of 48-year-old Andrei Kotov, whose death in a pre-trial detention center raised serious concerns about the pressure faced by those accused under the anti-LGBTQ+ laws.

Kotov was arrested in Moscow in late December 2024 on charges of creating an extremist organization related to his alleged organization of “gay tours.” Authorities added him to the federal terrorists and extremists registry, allowing authorities to freeze his bank accounts without a court order.

Before his death, Kotov said he had been beaten and tortured with an electric shocker in detention.

His lawyer told the BBC’s Russian service that Kotov “had no idea” his work could be considered extremism and that “he never managed to understand what exactly he was being accused of.”

Another activity that could lead to jail could be going to a nightclub or organizing a party.

The first criminal case for “organizing an extremist community” due to alleged LGBTQ+ affiliation was launched in March 2024. Vyacheslav Khasanov, the owner of the Pose nightclub in the city of Orenburg, was arrested along with staff members Alexander Klimov and Diana Kamilyanova.

All three were also added to the federal registry of terrorists and extremists.

In total, over 50 clubs allegedly associated with LGBTQ+ people or holding such events have been raided over the past year and a half under the pretext of fighting “LGBT propaganda,” said a joint calculation by Current Time and the Sfera Foundation, which helps LGBTQ+ people in Russia.

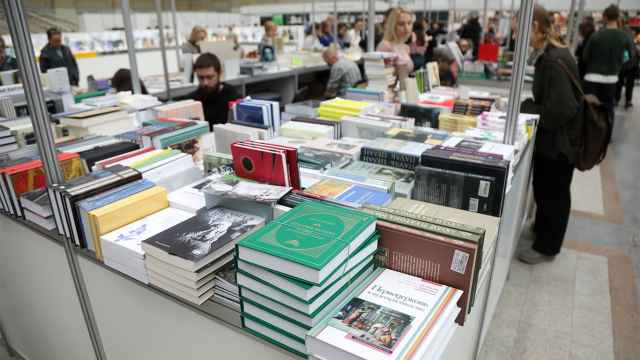

Literature has also come under scrutiny. In recent weeks, at least three major publishing houses — Samokat, Ripol and Eksmo — sent requests to booksellers to remove certain titles deemed to contain LGBTQ+ content from shelves, demanding either their return or destruction with written proof of disposal.

Last month, authorities arrested three employees of the independent publisher Individuum, accusing them of publishing literature with LGBTQ+ themes and charging them with organizing an extremist organization’s activities.

State repression has significantly worsened public attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals in families, schools, universities and workplaces, said Yan Dvorkin, the head of Center-T, an organization that supports transgender and non-binary people in Russia.

“People who were previously just transphobic or homophobic now feel empowered — to intimidate, blackmail and threaten others with administrative or even criminal prosecution,” Dvorkin told The Moscow Times.

LGBTQ+ Russians increasingly avoid disclosing their identity to doctors out of fear of discrimination. According to a recent report by LGBTQ+ organizations Vyhod and Sfera, nearly one-third (29%) of LGBTQ+ respondents said they had avoided medical visits at least once in 2024 due to fear of bias.

For transgender people, the figure is more than 50%. In 2023, Russia also banned gender-reassignment surgery and hormone therapy as part of the gender-transition process.

One 17-year-old transgender girl from Tambov told Center T’s discrimination monitoring team that a doctor refused to treat her because of her gender identity.

Olga, 18, from Kazan, said that during her gender transition, two complaints were filed against her at university due to her appearance — and that she was expelled as a result.

While the risks faced by LGBTQ+ people remaining in Russia are difficult to define, at least 83% of respondents in the report said they feel endangered following the decision to label the “international LGBT movement” as extremist.

For some, the current level of repression against their community has made emigration a near certainty.

“If I leave Russia, it will be 100% because of the LGBT propaganda law,” one gay person told The Moscow Times. “Everyone I know is planning to leave.”

According to Dvorkin, LGBTQ+ people are “increasingly retreating from public life in response to the repression,” which he said is leading to “the erasure of any mention, visibility or representation of LGBTQ+ people in the media.”

“We fought so hard for that visibility,” he said. “Because it’s the only thing that offers protection. When you’re visible, you exist — you can claim your space, your rights, your history,” he said.

“What’s happening now is erasure and it’s dragging us back into an era of fear and powerlessness,” he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.