Champagne. There is no other foreign product — with the exception of potatoes, perhaps — that has become so popular in Russia, first among the affluent, aristocratic public and then among everyone else. In Russia champagne became the people’s drink.

The first semblance of sparkling wine appeared in Russia at the end of the 17th century. In the villages of Tsimlyanskaya and Kumshatskaya of Kuban, there was a tradition of naturally “carbonated” drinks.

Legend has it that when Peter the Great was sailing from Voronezh to Azov on a ship of the new flotilla, he stopped several times on the lower Don. He thought that the local soil was suitable for winemaking. So he brought in gardeners and grape vines in from France. The vines were planted near the village of Tsymly, acclimated quickly and produced a good harvest. Peter was satisfied with the first experiments of Don wine-making. And after a trip to Europe, he sent the French several barrels of his Don wine.

But the French were also developing the vast expanses of the Russian Empire. In 1780, the winemaker Philippe Clicquot had sent a small batch of his wine to the Russian capital for sampling. Alas, due to the Napoleonic wars that followed at the beginning of the century, wine-related relations between Russia and France were resumed only in 1814. It was then that the House of Clicquot (renamed Widow Clicquot) began its expansion into Russia. Thanks to the entrepreneurial spirit and business talents of the young widow Barbe-Nicole Clicquot-Ponsardin, she achieved a very important result: champagne became a fashionable drink. In Russia it became a cult symbol of wealth and high society. For example, in 1825, 252,452 bottles of Clicquot champagne were sold in Russia. This amounted to almost 90% of its total production. Prosper Mérimée wrote: "The Widow Clicquot got Russia drunk."

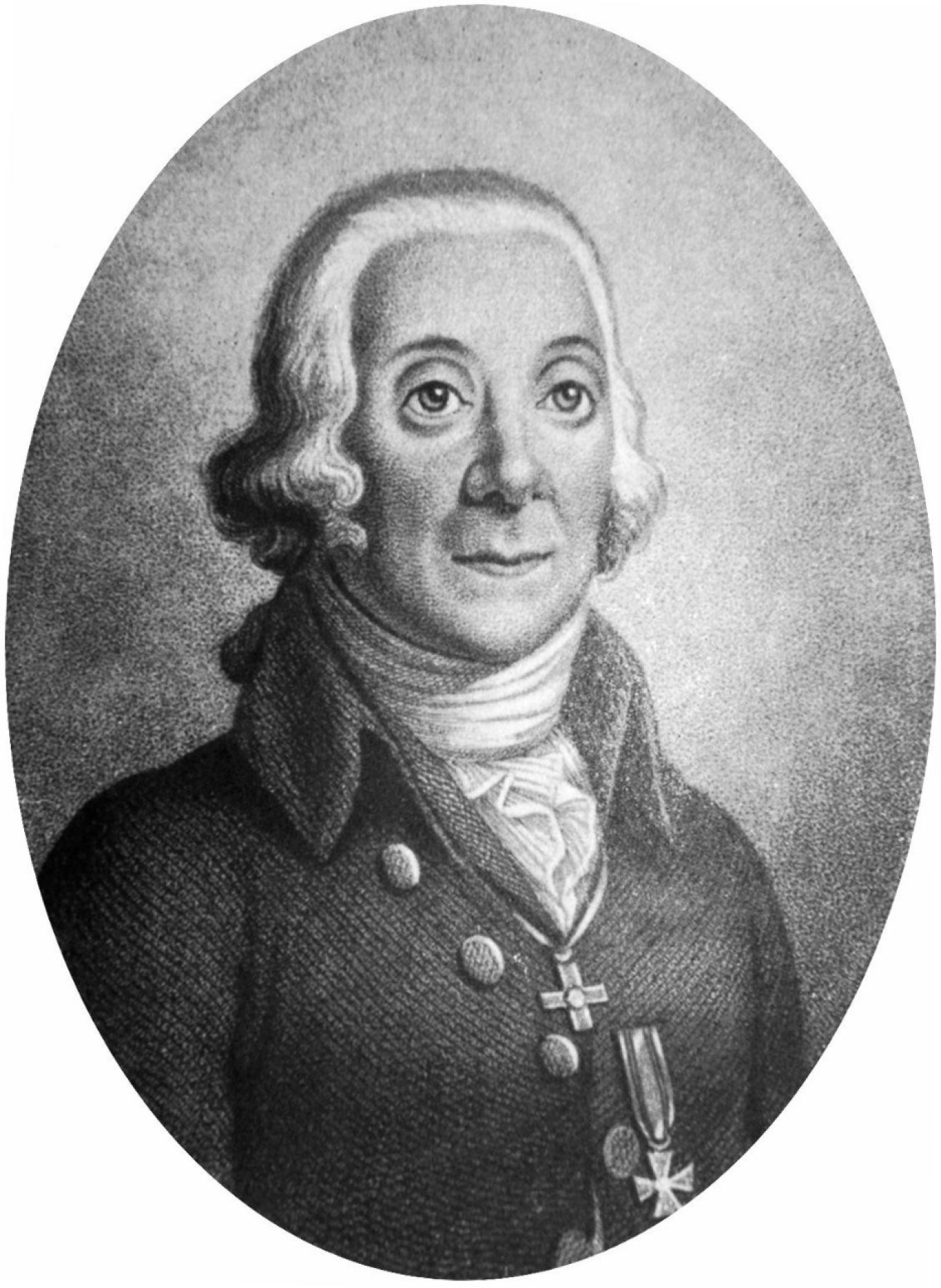

The serious business of champagne in the Russian Empire begins at the very end of the 18th century. In 1799 in the Crimean town of Sudak, the researcher Peter Pallas conducted the first experiments on the production of champagne wines. In the years the scientist lived there, from 1795 to 1808, he described more than 40 varieties of local grapes. In 1804 he established the first Russian Imperial school of viticulture and winemaking.

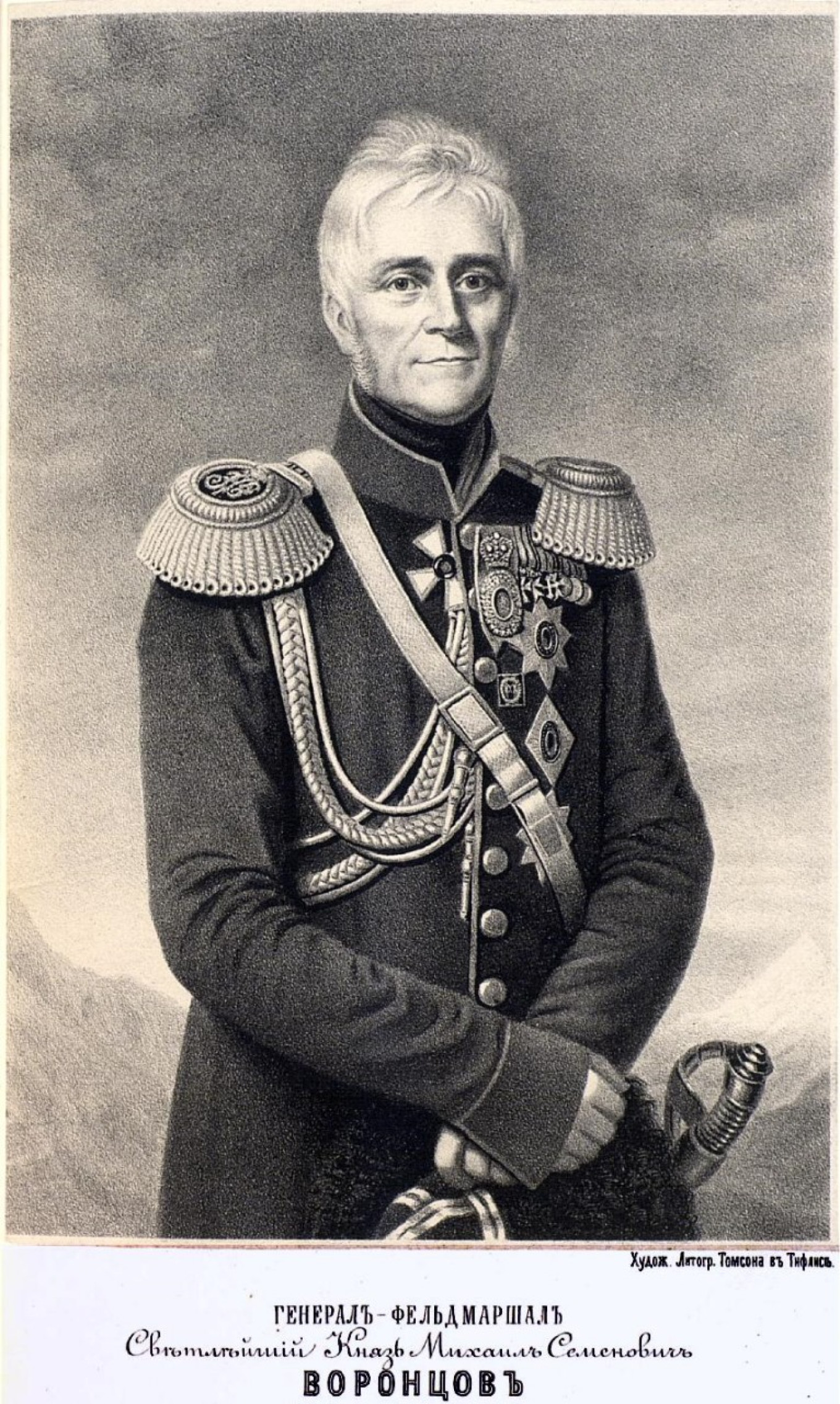

At that time there countless attempts to produce high-quality wine within the Russian empire. Among those who tried to do this was Count — and then from 1845, His Serene Highness — Prince Mikhail Vorontsov. His sparkling wine “Ai-Danil” had already been popular since the 1840s. Vorontsov was required by his position to develop local production. After all, since 1823 he was the Governor-General of Novorossiysk.

History often creates comical situations. Two lovers of champagne, remembered in the history of Russia for their passion for the drink were also romantic rivals in the early 1820s in Kishinev. Do you remember the poems by Alexander Pushkin about the "half-lord, half-cad"? They were about Vorontsov.

Half-lord and half-shopkeep,

Half-wise and half-infernal,

Half a swine — but hope springs eternal,

That one day he will be complete.

What happened between Pushkin and the Count’s wife, Elizabeth (born Countess Branitskaya) is difficult to determine today. And there’s no point. The important thing is that at some point their complicated personal lives became public, which was very unpleasant for both of the men. Vorontsov was constrained by official etiquette and official duties, but nothing kept Pushkin from pouring out his emotions in poetic lines. Which he did.

But back to champagne. The Crimean War and the Sevastopol campaign of 1855 seriously undermined the wine industry on the peninsula, and the consequences of the defeat affected the country's finances and trade for a long time. Perhaps that’s why for 10-15 years high-quality champagne from the Russian Empire was but a memory from the glorious past.

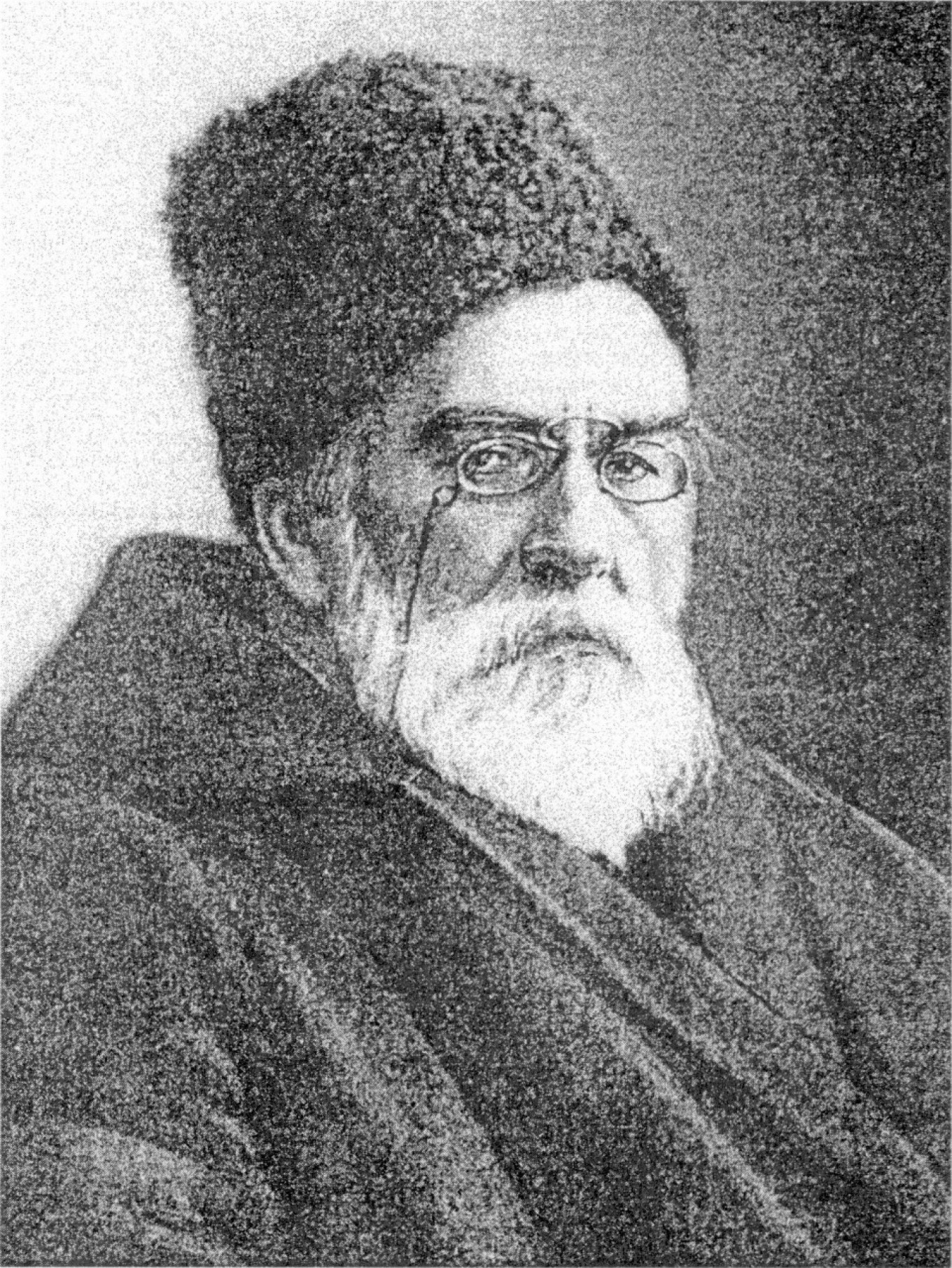

The main mover for its revival was Prince Lev Golitsyn (1845-1915). His work had incalcuable value. Starting from a modest vineyard near Feodosia, at the end of the 19th century he founded the village of Novy Svet (Ukrainian: Novyi Svit, called Paradise until 1912). At the beginning he opened a nursery where several hundred varieties of grapes were grown. Then he built a factory producing champagne that formed the town around it.

His triumph took place in 1899-1900. He produced 60,000 bottles — not very much for Russia, especially considering that in those years Russia imported up to one million bottles of French champagne. But it was this limited "circulation" that created Golitsyn's fame. In 1900 at the World Industrial Exhibition in Paris, a batch of his champagne was presented from the Russian Empire. A foreigner getting a prize in France for his foreign-made champagne? Even today it seems unreal.

And yet the miracle happened at a blind tasting of experts. All the bottles were wrapped in foil so that the names could not be read. When Count Chandon, chairman of the jury, asked to take the paper off the winning bottle, which had been chosen unanimously by the competition committee, few doubted that a French name would be announced. But instead he read "Novy Svet. Le Prince Golitsyn," not believing his eyes.

Champagne is an amazing product. Despite the subsequent World War and the revolution in Russia, it was revived, albeit having lost some of its elegance and exclusiveness. After all, in the USSR champagne was everyman’s drink, present on almost every table.

Champagne is not only wine, but also an ingredient in elegant Russian cuisine. Sterlet (a kind of small sturgeon) in champagne is probably the best-known dish. We once had a chance to cook it together with the chef of the famous Moscow restaurant "Yar." It is really something.

Sterlet in Champagne

River trout can be cooked in the same way.

(4 servings)

Ingredients

- 1 sterlet (trout) weighing about 1.5 kg (3.3 lb)

- 1 lemon

- 100 g (3.5 oz or 6 Tbsp) butter

- ½ bottle dry champagne

- 1 onion

- 1 tsp sugar

Instructions

- Gut the sterlet, wash in cold water. Cut off the top fins

- Bend the fish into a ring and place it in a wide saucepan or frying pan.

- Squeeze the juice of the lemon into the pan. Quarter the onion and add it, the butter and sugar. Pour in the champagne, cover, bring to a boil and then cook for 15 minutes.

- Serve the sterlet immediately while very hot.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.