In 1909 two girls, fifteen-year-old Alexandra and her younger sister Fevronia, left an ethnic Lemko village in the Carpathian Mountains, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, made their way to Bremen and boarded a ship to America. Four years later, two teenage brothers, Viktor and Mikhail, left their village in Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, and took a ship from Trieste to New York. The children took little of value with them, but they did have a painted tin teapot, a bolt of hand-woven cloth and a vyshyvanka (Ukrainian embroidered shirt).

Five years later Viktor married a young woman named Helen and opened a small store. They had four children, one of whom, Anastasia, was my mother.

Alexandra married a fellow Lemko émigré named Joseph. She had a daughter Anne and son John, who was my father.

At home my parents were Ivan and Anastasia. In the American world they were John and Stasia, an electrical engineer and a nurse. They spoke English everywhere (except with their parents), baptized their two children in the Russian Orthodox Church but later converted to Presbyterianism. My brother and I were two American kids who grew up on cartoons, piano lessons and baseball, and went off from a middle-class home to liberal arts colleges. We were a poster family for the American Dream.

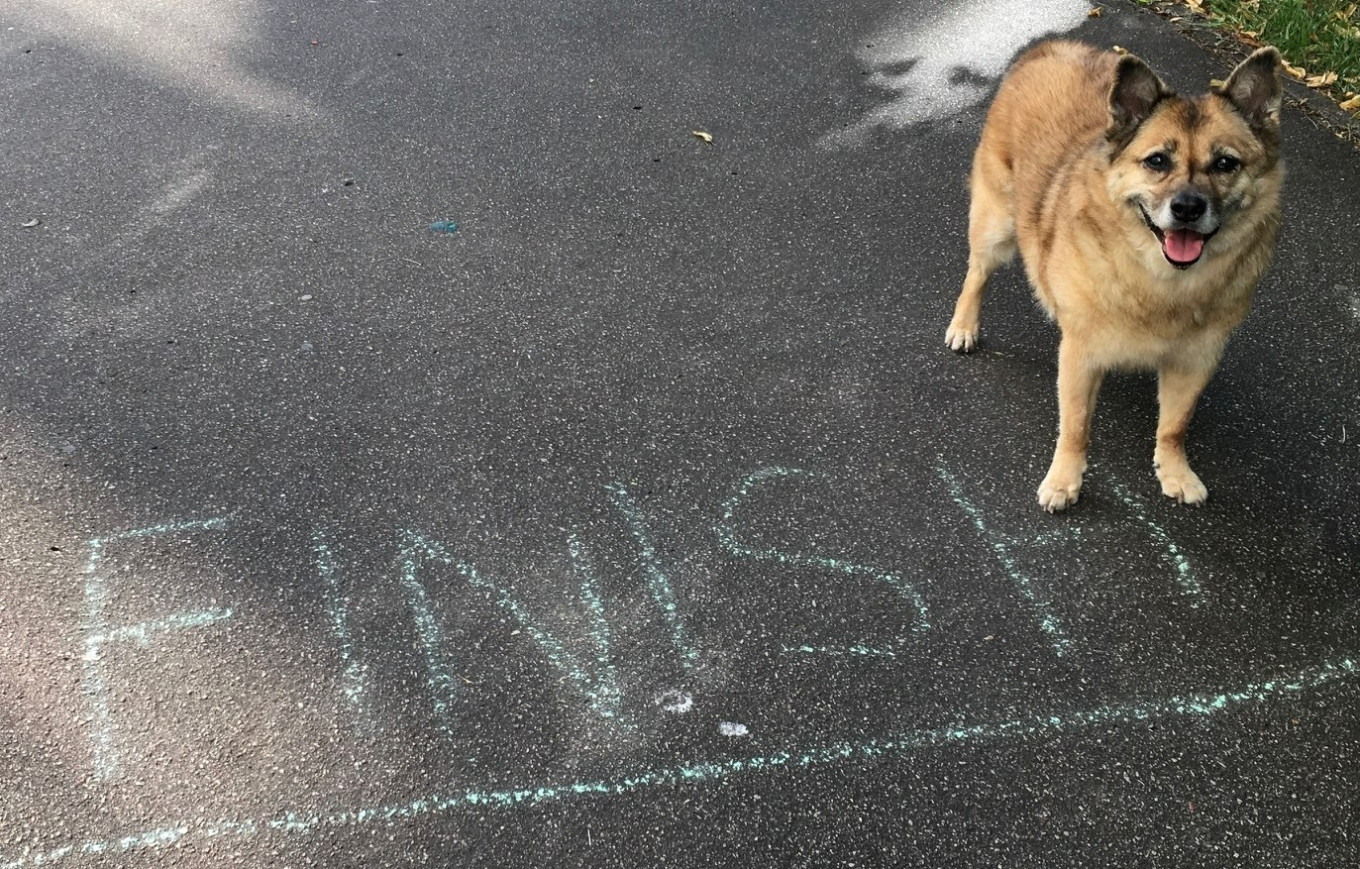

So, if you had told my grandparents that a century after they had fled European empires for better lives, their second-generation American, native English-speaking, Ivy League-educated granddaughter would flee a new version of the Russian Empire in the middle of the night with a suitcase and her dog — they wouldn’t have believed it.

There was clearly a family lesson I failed to learn.

When I left Moscow last March after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, I expected to have a difficult time adjusting to living in Riga: it would be a new country, a new language — a new everything. But it wasn’t that difficult. It seemed at first like the kind of long business trip I used to do. I knew the routine: Find the grocery shop and pharmacy, figure out the taxi situation, make friends with the neighbors.

It's easy to meet people when you have a friendly dog. My neighbors in the housing complex I settled in — called Zolitude (Solitude) I discovered with some dismay — were almost all Russian, mostly from the older generation who had moved or been posted there during the Soviet period. Many of them were disturbingly influenced by the Russian state media they were watching and reading (everyone had a VPN), but otherwise generous advising on everything from the best cheap health clinics to where to recycle plastic and glass.

The Latvians I met, all of whom spoke either English or Russian, were sympathetic, friendly, and kind. In six months I never met a rude person, which must be some kind of national record.

It was also easy to get settled in Latvia, which I kept calling in awe “a normal European country.” You can order something from Amazon and it arrives from the U.S. in six days. When it snows overnight the sidewalks are clear by 8 a.m. Strangers help you navigate the public transportation system. Latvians complain about all sorts of things — and with justification, I suppose — but when you arrive from Russia, the country seems like a model of responsible government and service.

After Moscow’s enormity — the 12-lane highways and three-hour traffic jams, the largest shopping mall in Europe, skyscrapers going up in every district — it is a delight to live in a city that is human in scale. Riga feels like a capital city: it has a turreted presidential palace, vast squares, ancient cathedrals, and — by the way — the largest concentration of art nouveau architecture in the world. But its narrow, cobblestoned streets and two-story wooden houses even in the city center are cozy and inviting.

I haven’t even minded living out of a suitcase, although I resent buying, say, phone charger cords when I have a pile of them in the second drawer on the left in my Moscow desk.

I have felt deeply uncomfortable that some of what makes Riga so welcoming to people from Russia is the 50-year Soviet occupation of the country. Some government office buildings look just like the ones built in Yekaterinburg or Novosibirsk— and probably had the same architect. About a third of the capital's population is Russian, and almost everyone you deal with, from salespeople to taxi drivers to veterinarians, speak the language. I once listened to a harried nurse move seamlessly from Russian to Latvian to English and back again without a second’s pause between languages.

I don’t know much Latvian. It is hard to learn; except for some borrowed words, Latvian has few cognates with the Slavic and Romance languages I know. I have read one book about Latvian history and have a kindergartener’s sense of Latvian literature. I can’t follow politics — except to be impressed by the great number of political parties. It is as if I’m color blind, missing most of the spectrum of light.

But all the same, one day after I’d been in Riga for about three months, I was crossing the bridge over the Daugava River when I caught sight of the church spires rising up over Riga’s Old Town. Suddenly my heart did a little leap of joy. It seemed like a miracle, to be that happy in a new country. I began to think of Riga not as a long business trip, but as a place to live, at least for a while.

If Latvia would have me, that is. Wanting to do everything properly, I hired a lawyer to help me apply for a long-term visa. That turned out disastrously. He had no idea what to do with an American journalist and gave me all the wrong advice. I had to go back to the U.S. and apply for a visa from there.

As I was preparing to leave, I ran into a Moscow neighbor in the Russian bookstore in Riga. I told him I was about to leave the country for a while — visa problems. “Visa problems, visa problems,” he said, waving his hand in the air dismissively. “Of course, you have visa problems. Everyone has visa problems. You’re a refugee.”

Me, a refugee? Impossible. But perhaps not: I might not have fled from my homeland, but I was a refugee from my home. I was terrified of losing another place I was beginning to love. I had a toehold in Latvia, I’d found a haven; if I lost that after all that I’d lost before, how could I bear it?

The thing is: I don’t much like change. Except for a few years in the 1980s, I lived in Moscow since 1978, my entire adult life. I moved into my Moscow apartment in 1993, bought it in 2003 and lived there ever since. I rented the same little house in a dacha community for almost as long. I liked to drive the same roads back and forth between house and dacha, looking forward to the first sight of a little church I liked along the way. In my apartment I didn’t move around the furniture or paint the bedroom a different color. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, right?

Now it is broke, all of it.

But in my worried and sleepless nights — I have not slept straight through the night in a year — sometimes, just sometimes, there is a faint lift of almost excitement. I fell in love with a country I’d never even been to before. I am in Europe. I’ve met dozens of new people. I can celebrate the summer solstice — a four-day national holiday. I’m learning the grammar of an ancient language and finding new artists to love. I’ve remembered the thrill of discovery.

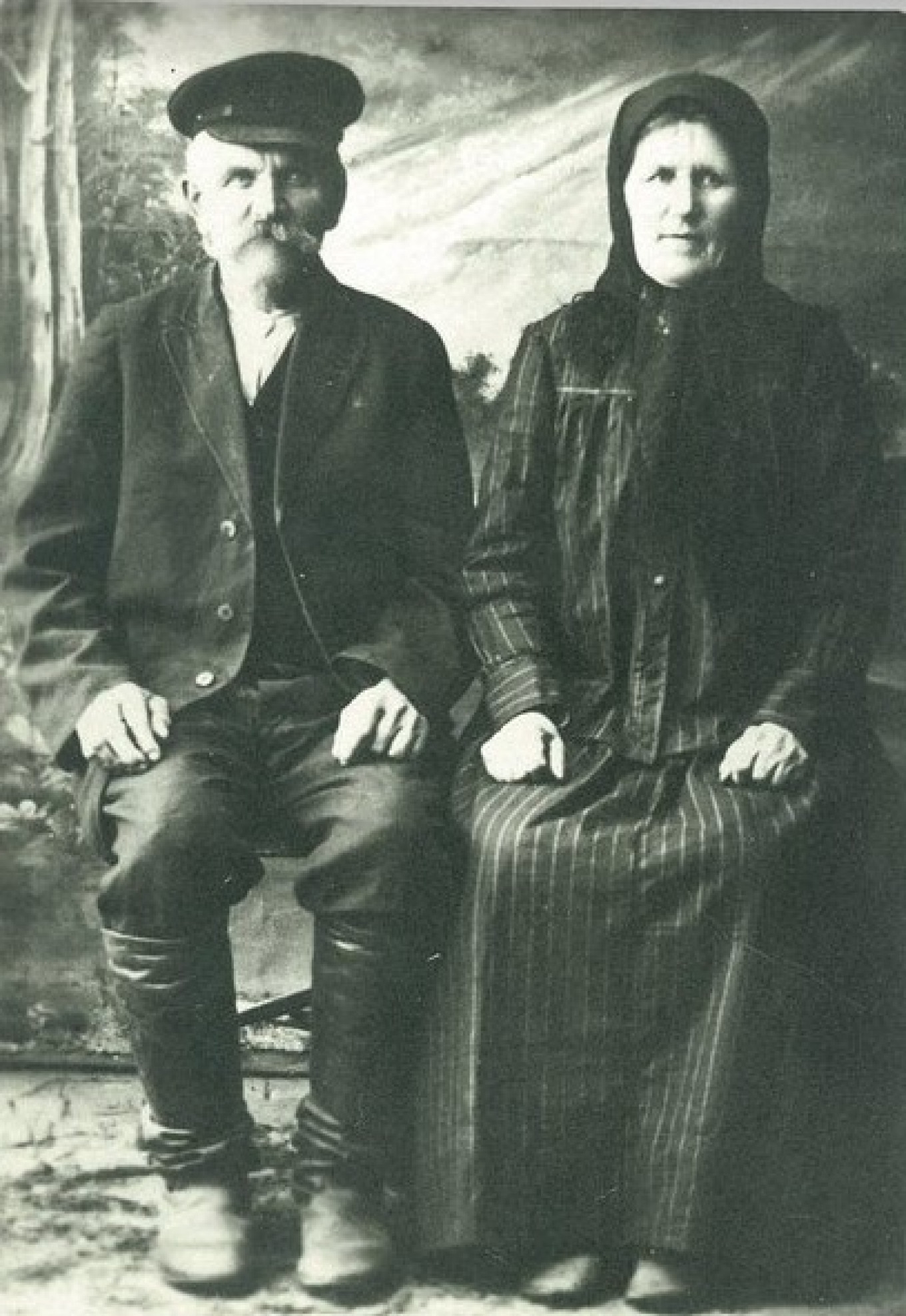

Before my grandfather Viktor and his brother came to the U.S., their father Kiprian had gone ahead and found work in the mines of Pennsylvania. When Kiprian had settled his sons in jobs, he returned to his village in Ukraine with plans to return with his wife and daughter. But it was 1917 before they were ready to leave. I remember hearing as a child — although now I think I made up a romantic story — that the family crossed the country and tried to leave from Vladivostok but couldn’t get out.

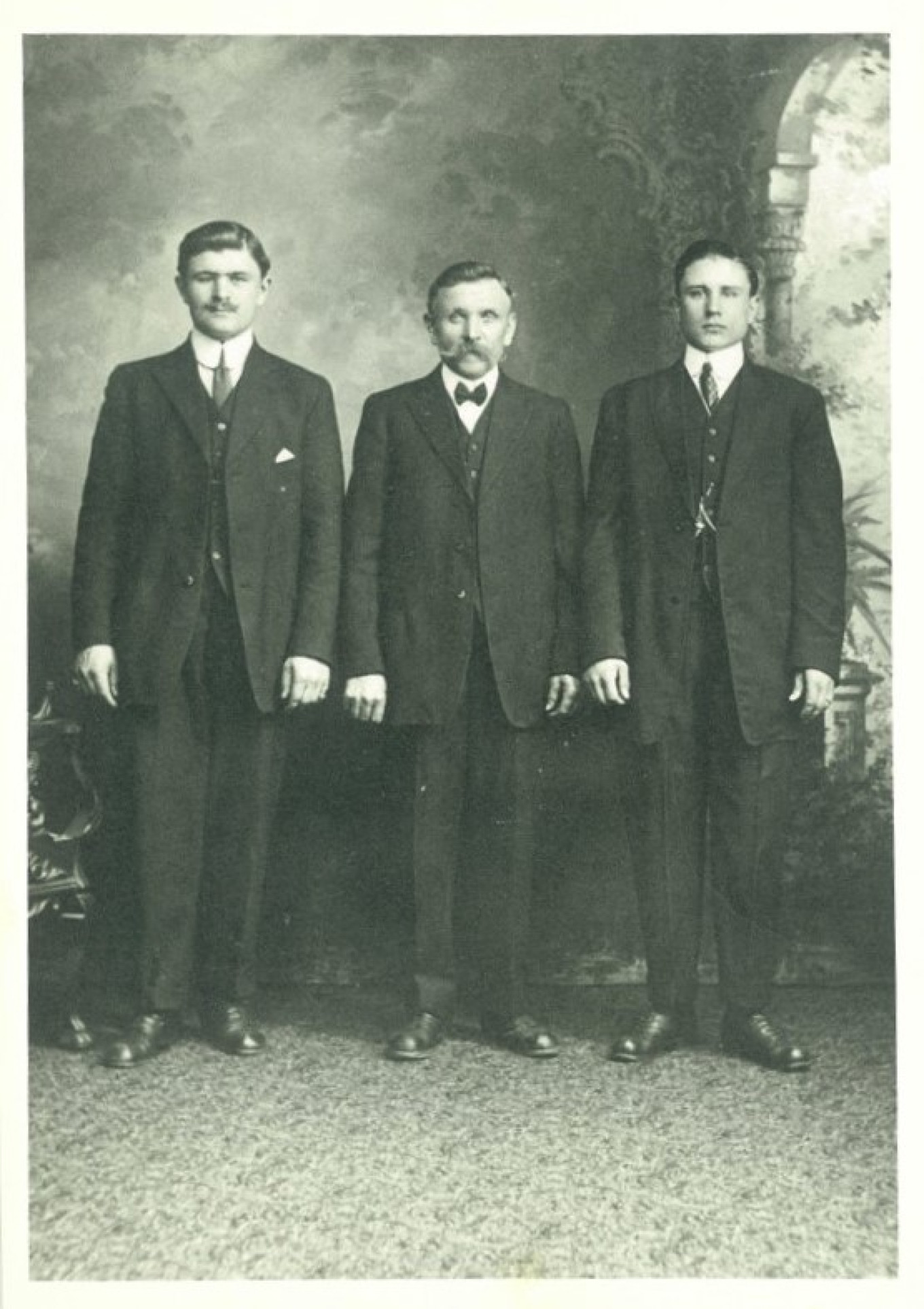

Over the years the brothers sent home money, sewed into the hems of dresses for their sister or tucked in picture frames behind photographs of them, standing stiffly in their American suits. In the 1930s their Ukrainian family told them to stop writing. In the 1960s, during the Thaw, their sister began to write again.

Although Viktor read émigré newspapers and was active in a very anti-Soviet Orthodox church, he had created a rosy picture of the U.S.S.R. Despite warnings and worries, in 1968 he applied for a visa to visit his sister and her grown daughters in Moscow. He and his sister hadn’t seen each other for 55 years; she had been a child when he left. In New York, the entire family — all his children, wives and husbands, grandchildren, cousins, nephews and nieces — saw him off from John F. Kennedy Airport with bottles of champagne and misgivings.

He came back a month later shocked and disillusioned. For months all he could talk about was the poverty, the backwardness, the tiny apartments and shoddy goods, and how his relatives believed state propaganda. I remember him shaking his head over the years he had wasted imagining a different place, a modern and happy version of the home he’d left.

I’m trying to get it right. I do not look back. I have no illusions about the future. Until the war is over and there is repentance — reparations, change — I will not go back. My eyes are on the spires rising above the Daugava and beyond. That’s one family lesson I did learn.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.