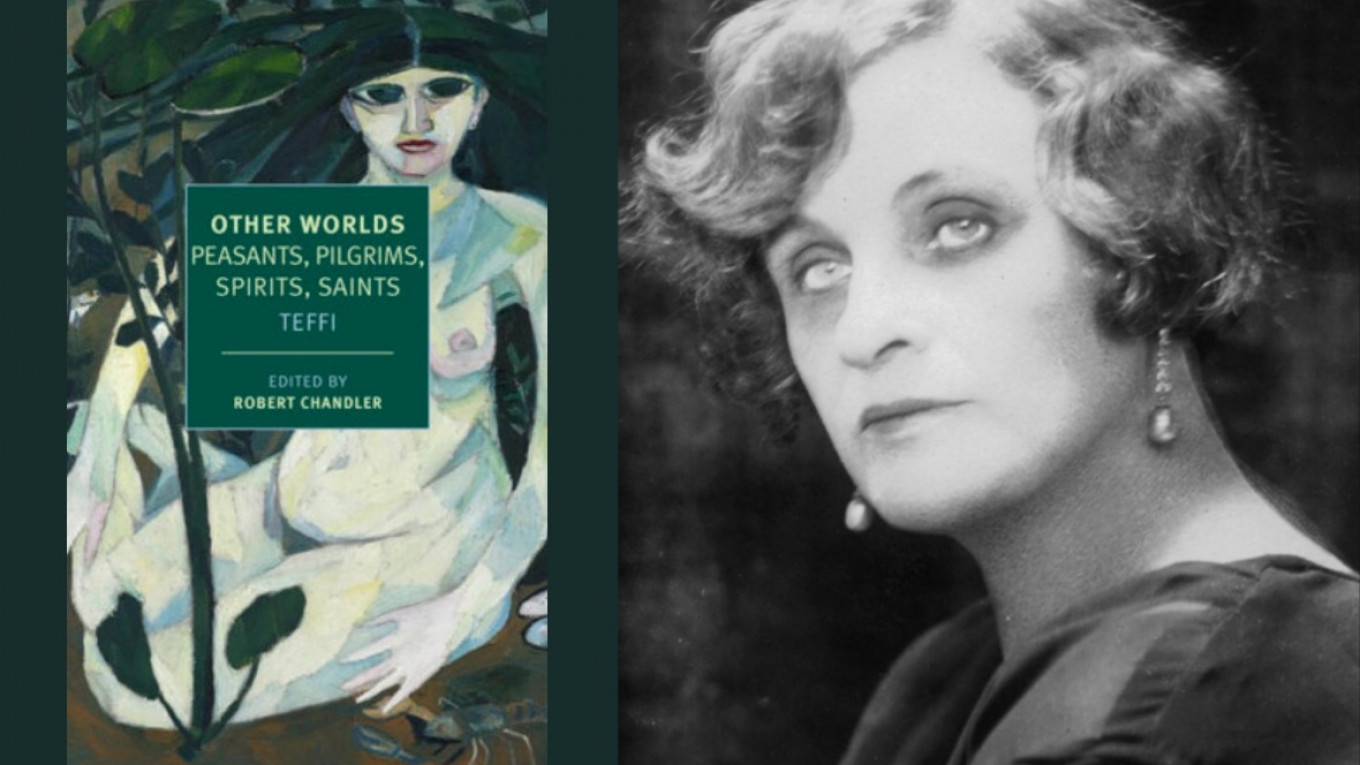

This Translation by Robert Chandler

Teffi is difficult to translate. I have said a little in the foreword about her Pushkinian grace and deft use of repetition. She also makes the most of two freedoms—the freedom to omit words and an extreme freedom of word order—that are available only in a highly inflected language like Russian or Latin. And the precision of her psychological understanding, visual descriptions, and references to details of nineteenth-century Russian life leaves a translator with no room to maneuver.

Her use of dialect and substandard speech presents a particular difficulty. Many of the stories are set in Volhynia, in what is now western Ukraine, and the peasants and less educated characters speak a language heavily influenced by both Ukrainian and Polish. There is no logically satisfactory way of translating such speech. On the one hand, much of the texture of these stories is lost if all the characters—educated and uneducated alike—are made to speak the same standard English; on the other hand, translating their speech into a particular English or American dialect risks disorientating a reader, making him or her feel they have suddenly been transported to, say, Somerset, Yorkshire, or Appalachia. In the end, the latter risk seemed worth taking—if only because I had the good fortune to know two translators, Pavel Gudoshnikov and Sian Valvis, both of whom have an unusual gift for reproducing Yorkshire dialect. With their input, our versions of several of these stories—especially of some from The Lifeless Beast, where Teffi deviates most boldly from standard Russian—have gained greatly in poetry, humor, and vividness. I should also explain that I asked Valvis to introduce a hint of Scots into the dialogue of “Solovki,” which is set in the Far North of European Russia.

All these translations are the fruit of collective vision and revision. All those credited as translators of individual stories have also read the entire book and made helpful suggestions with regard to many of the other translations. And I have used most of the stories as texts for translation workshops at Pushkin House, in London. Participants have often come up with good, lively turns of phrase that my wife, Elizabeth, and I have eagerly incorporated in our final versions. Native speakers of Russian have also drawn my attention to many passages in the original that I had initially misunderstood. Teffi’s apparent simplicity often veils unexpected subtleties; I almost always underestimate her work on first reading.

If we read Teffi in Russian, we feel that we are listening to a living, speaking voice—not just reading words intelligently arranged on a page. The greatest difficulty for a translator lies in reproducing this immediacy, this illusion of spontaneity. The simplest words, paradoxically, are often the hardest to translate. Two short sentences about Baba Yaga, for example, proved surprisingly difficult. Though not especially original, the Russian is pithy: “Sku–u–u-uchno (B-o-r-i-n-g). Skoree (sooner) by (if only) zima (winter).” We published an earlier version of our translation of this article in the anthology Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov.1 There we translated these two sentences as “She feels b-o-r-e-d. If only winter would come soon!” This is accurate, but I can’t hear the intonations of Baba Yaga’s voice. It was only recently that we changed it to “Would winter never come?” This has the ring of speech—and the right plaintive tone.

One of the joys of running a translation workshop is that almost every participant makes at least a few valuable contributions. Even someone relatively unschooled or inexperienced will sometimes suggest a brilliant solution I would never have thought of myself. In a description of a group of people walking across a grass-covered bog, Teffi writes that “beneath the velvety green carpet they could sense sticky, viscous, quagmiry death.” In the original, the last four words (lipkaya, tyaguchaya, tryasinaya smert') are expressive, even onomatopoeic. We struggled over them for some time. The word “viscous” was clearly unsatisfactory. It is a dull, rather scientific word, and too similar in meaning to “sticky.” It was a secondary-school student, Sophie Benbelaid, then only seventeen and less than half the age of anyone else present, who came up with “treacly.” We all immediately recognized that this was perfect— perfect—above all, perhaps, for being so unexpected an adjective to use of death. And we quickly agreed on a final version: “Hidden under the velvety green carpet lay sticky, treacly, quagmiry death.”

There are many features of Teffi’s style that I first consciously noted only while working on this book, as I tried to understand what made a particular sentence seem dull and pedestrian in our draft even though it was lively and graceful in the original. Teffi’s pacing, her handling of transitions, is fluent and delicate; our first drafts, in contrast, often sounded either ponderous or jerky and disconnected. And Teffi’s syntax is unusually flexible. The first sentence of “Water Spirit” is performative; the syntax enacts the narrator’s growing anxiety as she travels alone through remote countryside. The first third of the sentence reads as if lifted from a dull guidebook. The syntax then becomes less controlled, and the tone more desperate. By the end of the sentence, the syntax has fallen apart; the last three words—gloosh', dal', oozhas—sound like wild exclamations rather than descriptive statements.

In English, Teffi’s single long sentence seemed to work best as a series of short sentences. Our final version runs as follows: “The town was just thirty versts from the railway station, and it was forest, bogs, and more forest all the way. Rickety wooden bridges dancing across wild streams. Backwoods. The back of beyond. Dreary, dreadful, godforsaken.”

It is those last three words—gloosh', dal', oozhas—that were hardest to translate. The repeated long vowels—oo, aa, oo—are crucial; they do much to convey the narrator’s sense of fear and horror. And two of these words have no English equivalent. The noun gloosh' is cognate with glookhoy, a common adjective meaning “deaf,” “muffled,” or “muted.” Nicolas Pasternak Slater writes, “Gloosh' is untranslatable. It carries the feeling of a dull sound that is almost silence, at the same time as the remoteness of the back of beyond.”2 Dal' means something like “distance,” but it is more colloquial and expressive. Oozhas, at least, is relatively translatable—except that “horror,” while conveying the dictionary meaning, lacks the long oo that is so important in the original.

Our version evolved only gradually. Since a literal translation is not even possible, we tried to compensate for the inevitable losses by means of alliteration, assonance, and repetition. “Backwoods” evoked “back of beyond.” “Dreary” and “dreadful” seemed a natural pairing; for some time our last sentence read simply, “Dreary and dreadful.” Eventually, however, I realized that this sounded too neat, that it lacked the necessary emotional intensity. The addition of “godforsaken” allowed the sentence to echo on in the mind. I was pleased when my friend and colleague Maria Bloshteyn wrote, in response to this last change, “It now sounds almost like a hex or a spell. Teffi would have loved that.”

It has been said that the first letter of the Hebrew Bible is untranslatable. Nevertheless, the Bible as a whole evidently can be translated. Something similar is probably true of any great work of literature, however universally it has been recognized; there will always be at least an occasional sentence where the author has made such creative use of the most specific resources of a particular language that any attempt to reproduce this sentence in another language is bound to fail. Since Teffi’s linguistic creativity—the poetry of her prose—has yet to be properly acknowledged, I shall end by quoting a virtuoso passage from “Shapeshifter”: I dolgaya, dolgaya, tianulas' doroga. Sierdtse bolielo ot bieloy toski besprediel'nykh snegov. Literally, this means, “And long, long, stretched the road. Heart ached from white anguish of boundless snows.”

Like the sentence quoted earlier, this sentence is performative. The repetitions of the word dolgaya and of the syllable iel enact the sheer vastness of these white spaces. The final occurrence of iel is especially effective, since bespredyel'nykh (“boundless”) would stand out anyway because of its length. As for “white anguish,” this is as unusual in Russian as in English; it gains added resonance, however, from its similarity to “white fever” (bielaya goriachka)—a standard term for delirium tremens.

Our final version of this sentence is acceptable, but no more than that: “The white anguish of the boundless snows, the monotonous jingle of our bell, the motionless, evil figure beside me—all this made my heart ache.” This conveys the meaning of the original and some of its feeling, but it is not—like the Russian—something that anyone is likely to remember by heart. Nevertheless, as often happens, English then offers us at least partial compensation for these losses. Our next two sentences read, “The driver swayed silently in his seat, as if dead. Ahead loomed the dead of night.” The curt final sentence works extremely well in English. In the original, “dead” serves merely as an ordinary adjective, agreeing with “night.” English allows us to use the more idiomatic “dead of night.” The bleak context reinvigorates the idiom, and the repeated “dead” takes on still more weight from the rhyme with “ahead.”

One of the many reasons I so often choose stories by Teffi for translation workshops is that she has an unusually wide appeal. Regardless of age or literary taste, most readers warm to her. Erica Wagner concluded a London Times review of Memories with the sentence, “Teffi is a courageous companion for anyone’s life.” Nicholas Lezard began a Guardian review of Subtly Worded, our first collection of Teffi’s stories and articles, by saying, “Pushkin Press has done it again: made me fall in love with a writer I’d never heard of.” Other reviewers and readers have responded in a similar vein. There is no doubt that Teffi evokes in her readers an unusually strong sense of personal connection.

It is now well over fifteen years since Elizabeth and I translated two of Teffi’s stories for our first Penguin Classics anthology, Russian Short Stories from Pushkin to Buida—and we can certainly say that she has been an engaging and rewarding companion. We admire her wit, grace, and courage more and more as the years go by. And she has a gift for bringing people together; my workshops and e-mail collaborations have been a constant joy—both at the time and in retrospect.

NOTES

- New York; Penguin Classics, 2012.

- Personal e-mail, June 2020.

About the House

Everyone, of course, is familiar with the house spirit—the domovoy.

The domovoy is a serious being. He is fair and just, and he takes care of the house, all family concerns, and the stables. For some reason, he’s not interested in the other animals—only the horses. That’s probably why it’s so easy for witches to steal other people’s milk; the domovoy doesn’t protect cows.

This doesn’t mean that witches actually slip into other people’s cowsheds. What they usually do in order to steal milk is place a harrow upside down in their yard and draw milk from the tines. All they need do is call to mind the other person’s cow. Milk flows from the tines of the harrow, and the cow in question dries up.1

But all that is women’s business—no concern of the domovoy. His concern, as we’ve said, is the house and the stables.

For the western Slavs, and in a few parts of our own country, things are different. They have a number of smaller beings looking after their houses. These little beings are everywhere; they have their homes in every corner, behind the stove, under the bench, in the entrance room, in the larder, in corn bins, under the floorboards. Sometimes they quarrel. They squeal and have little fights. Clever people say that it’s mice scampering about. But how can it be mice when none of your fatback’s been stolen? Still, know-it-alls always know best.

A Polish woman once told me how, late in the evening, one of these beings drank some of the strainings from a fruit liqueur she’d just made. He overdid it—and forgot the whereabouts of his little home. Wherever he looked, someone was already there. Each of these beings, after all, had their own particular spot. So he rushed about anxiously, squeaking and squealing, and kicking up small clouds of dust. In the end, he got inside a pot that had had sour cream in it. And closed the lid after him. The following day the Polish woman kept hearing little giggles as she went around the house. Evidently, these little beings were having a good laugh. And there were smears of sour cream everywhere—under the bench, on the floor of the stove, and in every corner. The poor fellow must have ended up with sour cream all over him.

These small beings are good-natured. They never do evil, though they sometimes play tricks on you. They sprinkle your salt on the floor or roll your thimble away. They like hiding things: an old man’s glasses, an old woman’s needle, a young girl’s hair ribbon.

When that happens, you must tie a knot on your belt or in your kerchief, or twist some string tightly around a chair leg, and chant:

Play, little devil, play—

But give me back

What you take away!

And he’ll do just that. Straightaway. Because they’re quick, fidgety folk and there’s nothing they hate more than being tied on a leash. But you must never forget to untie the knot once the lost thing’s reappeared. If you leave the knot tied, they’ll never help you again. And anyway, why torment them?

As long as you behave decently, these little beings are kind and affectionate. They do all they can to warn you of any approaching trouble. But this isn’t easy for them. They can’t talk. They can only tap and knock. They let out quiet sighs. They rustle about in corners or whimper in chimneys. They twitch a curtain or tug very gently at your dress. Little signs like that are all they can manage.

If someone falls ill, they come out to help. They make such a to-do at your bedside that you can sometimes glimpse them with your naked eyes. Usually, though, they are adept at staying hidden.

I once heard this from a woman who was convalescing: “The doctors told me my temperature wouldn’t go up any higher, but in the evening, when everyone left and I was all on my own, I could hear something almost like whispering. From just behind me: ‘No, no, she’s still in a bad way. Still a lot of poison under the ribs. Here—and by her liver, and to the left . . .’ “

This whispering went on for a long time. They were concerned; they clearly felt sorry for me.

“‘No!’ I heard. ‘She’s not yet over the worst!’ I turned over very quickly and saw two strange beings. One was like the green leaves of a pineapple, but longer and more attenuated. The other was like a large, flat glass ruler standing on end, with a pleated headdress like a chambermaid’s. They both had gleaming eyes, like little beads. When they saw I’d turned over, they darted behind the screen.

“And they were right. I wasn’t over the worst. The next day my temperature rose still higher. And I can remember groaning with pain when the fever was at its peak and I tried to turn over in bed. The doctor just said, ‘She made an awkward movement.’ And then I heard tiny whispers from all around the room: from under chairs and tables, from behind pictures, from behind each flower on the wallpaper: ‘An awkward movement. An awkward movement. Whisper-whisper-whisper . . .’

“Frightened little eyes were gleaming at me.

“‘An awkward movement!’

“They were frightened on my behalf. Very anxious indeed. They really are very sweet.”

When you move to a new home, you must leave saucers of milk and honey beside the hearth. You must also offer these beings something on the night before Christmas, because this is a sad and painful time for them.2 It’s the eve of their great fall, the eve of the birth of He who took away their human souls. They also need comfort before the beginning of Lent, as Butter Week draws to an end. Fasts, gloom, and churchgoing—they find all that both dreary and hurtful. And you don’t want to hurt them, since they’re sweet and good-natured.

Not like the domovoy. A Russian house spirit can be very bad-tempered indeed. He likes to pinch plump girls. He chokes stout old gentlemen during the night. He’s a real martinet—he likes to scare and intimidate. All in all, he’s like some petty tyrant of a small landowner. Fanatically conservative about every tiniest matter, refusing to acknowledge anything new. He even goes out of his way to damage new furniture. He makes it split and crack during the night—you can’t not hear it.

These little beings aren’t like that at all. They certainly don’t try to frighten people—they’re much too frightened themselves. Life isn’t easy for them. Some little fellow makes a home for himself in the cockroaches’ corner behind the iron stove, in a spiral of dust. Then someone comes along with a broom—and that’s the end of his bolt-hole. Where can he go now? Everywhere’s already taken. And if you’ve lived all your life in a comfortable spot behind a chest of drawers, you’re not going to be able to make your home in even the very best of stove vents.

Nor are they in the least scared of innovations. Even something like a golf-club bag suits them fine. They wait till the dust has built up for a while, and then they settle down inside it. All that matters to them is that you should stay in one place—the one thing they can’t do is accompany you if you choose to move house.

In the old days, when families lived for centuries in the same nest, these beings all had their assigned places and knew what was what. And everyone—generation after generation—knew that there’s something in one room that squeaks, something in another room that keeps tapping away, and that there’s a third room where, during the night, it sounds as if someone keeps rolling a nut across the floor.

And nannies went on threatening children—generation after generation of them—with the same dark corner of the nursery: “That’s where the buka lives. If you’re not asleep in good time, he’ll give you what you asked for. Thwack, thwack, thwack!”

Nannies never described the buka or told their charges anything about him. It was left to each child to imagine someone uniquely horrible and frightening.

The buka was the nursery spirit. He was in charge of the education of small children and his hour was in the evening, as we were going to bed; his role was to make sure we didn’t get up to mischief and went straight to sleep. He belonged to the night. During the day nobody even mentioned him; not even the stupidest nanny would try to threaten her children with him before it got dark.

In the old days, if a family didn’t live all year round in one place, but, say, spent the summer in the country and then moved back to the city for the winter, a few of these smaller beings might follow their masters, but most of them stayed behind in their familiar haunts.

And as for some shaggy little creature used to living under the carpet on a grand staircase—what will become of him in the country? He’ll catch cold in no time at all. He’ll get chilled to the bone from some draft and then sneeze himself to death.

The domovoy, of course, is still less likely to go anywhere. As his name implies, he is domestic; he is responsible for the house and cannot be moved from it. If the house is sold to a new owner, or is left to a relative, the domovoy stays put. And if he doesn’t like the new owners, you can be sure he’ll make his feelings known. A domovoy may grieve deeply when a family close to his heart, a family that’s been around for hundreds of years, moves to another home. But no matter how deep his anguish, he cannot leave the house and go with them. He belongs to the house.

Can these little beings be seen? They can—but not by everyone.

They can only be seen by children, by people in bed with a high fever, and by drunks. And not by any old run-of-the-mill drunk, only by the well and truly blind drunk, by those who can see double.

I once happened to see such a drunkard myself. He was sitting opposite me on a tram, so I had plenty of time to observe him. The poor pie-eyed fellow was obviously infested with these little imps—he kept blowing them off his sleeve, flicking them off his knee, or shaking them from his lapel. From the way he acted, it was clear that they were tiny, not in the least scary, and very boisterous. Judging by what I’ve heard tell, that’s how they appear to everyone who’s truly blind drunk.

Beings like that don’t even really belong to the house at all. They’re just small fry, insignificant beings with no party allegiance or sense of responsibility. They certainly aren’t doing the drunkard any harm. If he flicks them away, it’s merely because he’s embarrassed—their presence shows only too clearly just how drunk he is.

Or maybe he simply finds it disgusting to have such trash settling on him—crawling all over him like flies.

Anyway, even if not all of these beings are particularly pleasant, they are at least harmless.

Whereas the spirit I’m going to tell you about now is spiteful and evil through and through. I wouldn’t wish anyone to encounter him.

His name is . . . But let’s leave that until the next chapter.

Translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler

NOTES

- Compare Zelenin: “For Ukrainians and Belorussians, a witch’s main activity is stealing milk from cows. If a witch milks a cow on the Feast of the Annunciation, on Easter, or on Saint George’s day (April 23), only she can then continue to get milk from that cow. The milk flows from an aperture in one of the logs of the witch’s home, if you turn on a tap there”; in D. K. Zelenin, Vostochnoslavianskaya Etnografiya (Moscow: Nauka, 1991), 421.

- […] Teffi may have in mind the belief that some of these spirits are the unclean dead—former human beings who no longer have souls because they were denied a Christian burial.

Excerpted from “Other Worlds: Pilgrims, Peasants, Spirits, Saints” by Teffi, edited by Robert Chandler and published by New York Review of Books, 2021, with translations by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler, Agnès Szydlowski, Maria Bloshteyn, Anne Marie Jackson, Sabrina Jaszi, Sara Jolly, and Nicolas Pasternak Slater. This translation by Robert Chandler, Elizabeth Chandler, copyright © 2021. Used by permission, all rights reserved. For more information about this book, see the publisher’s site.

Robert Chandler's article about translating the story "Solovki" can be found here. You can read more of Teffi's writing with this excerpt from “Memories,” Teffi's last journey across Russia and Ukraine, before going by boat from the Crimea to Istanbul, in 1919 published in The New Yorker.

For more information about Teffi, translation, and this collection, see the Community Bookstore video below.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.