IZHEVSK — It was a Tuesday morning like any other. Albert Razin, a 79-year-old activist, stood outside the State Council building in the capital of Russia’s republic of Udmurtia holding two handwritten signs.

One read: “Do I have a fatherland?” The other quoted Soviet Avar poet Rasul Gamzatov: “If tomorrow my language will be forgotten, I am ready to die today.”

Ever since the late Soviet period, Razin had been a noisy fixture of public life in Udmurtia, a frail professor demanding rights for the indigenous Udmurt culture. For the deputies passing by him on their way to work, the scene was nothing out of the ordinary.

Then, at 9:36 a.m. on Sept. 10, Razin lifted a lighter to his chest and set himself on fire. Witnesses say he didn’t utter a sound, even when rushed to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead before lunch.

“One moment you’re saying good morning to your friend, the next you’re sprinting out of the building with a fire extinguisher,” said Leonid Gonin, a senior aide to local United Russia deputy Alexei Zagrebin, who had known Razin for years. “It’s hard to put into words.”

Razin’s self-immolation has left a community in shock, asking itself what drove the activist to such a desperate final act. While some have dismissed him as a radical who lost his mind late in life, for others his protest has brought into stark relief an inescapable fact of modern Russia: the slow erosion of its myriad ethnicities.

Udmurtia, which sits between the Volga River and the Ural Mountains some 1,300 kilometers east of Moscow, is one of Russia’s 22 autonomous regions. Together, they include 35 co-official languages alongside Russian, in addition to another 100 or so spoken across the country. Many of the co-official languages are part of the family of Uralic or Finno-Ugric languages spoken in the autonomous regions along the Volga river, including Udmurt.

Much of Razin’s anger was aimed at a system that had never made Udmurt required learning in schools across the republic.

“When I was growing up we were required to study Russian and English, but not Udmurtia’s indigenous language,” said Andrei Perevozchikov, a 32-year-old blogger and activist who considered Razin his mentor. “He understood that it’s the essential part of our culture. If we don’t have our language, everything else will fall away.”

Born in an Udmurt village during World War II, Razin graduated from Udmurt State University in 1962. The university, where he would later teach and found an institute dedicated to preserving Udmurt culture, is in the capital city of Izhevsk, where nearly half of the republic’s 1.5 million people live, 30% of whom are Udmurt.

While Razin grew up speaking Udmurt, in Izhevsk he encountered a city in which the language is largely absent. Unlike the neighboring republic of Tatarstan, where street signs are in both Tatar and Russian and Tatar can be heard on the streets, Udmurt in Izhevsk is only spoken among committed activists.

“Today you’ll only hear it in villages,” said Alexei Shklyayev, a local Udmurt activist. “People are embarrassed to speak it in Izhevsk because it’s seen as being lesser than Russian.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, Udmurtia and the other autonomous republics along the Volga experienced an industrialization boom that brought an influx of Russian workers. The result, said Natalia Zubarevich, an expert on Russia’s regions, was the steady assimilation of local cultures — in some of the republics more so than others.

Some have tried to fight against that trend. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, local intelligentsias saw an opportunity to promote their cultures given that the new constitution saw Russia as a federation, Zubarevich said.

Razin was a central figure in Udmurtia’s national movement. In November 1991, he co-founded the Udmurt Kinesh — the Udmurt Council — which today sits in the State Council, the building outside of which he protested and died.

Razin didn’t believe that much had changed for the better over the years.

“He often woke up in the middle of the night and lay there staring at the ceiling thinking about these problems,” his widow Yulia Razina told The Moscow Times in an interview at the family’s small apartment in a Soviet-era building near Udmurt State University, where she teaches.

Part of the reason for the decline of Udmurt identity, said Zubarevich, is that in recent years urbanization has been taking hold across Russia, with populations moving from villages to urban centers. In Udmurtia, that has meant swapping Udmurt for Russian. Between 2002 and 2010, the number of Udmurt speakers fell by 30%, according to census counts. In 2011, the UN's Atlas of Languages in Danger described Udmurt as “endangered.”

In interviews, local activists, Razin’s close colleagues and his immediate family all said he fought for more than just the preservation of language. But in recent years, he felt that his ideas were being rejected wholesale and that the authorities were ignoring him.

One key flashpoint was a local park in Izhevsk that Razin wanted to have declared a sacred site as it used to be an ancient Udmurt village. In the since temporarily shelved project, local officials wanted to build modern amenities there, and an activist close to Razin said he believed there were plans to build elite apartment buildings on the site.

After Razin’s death, the president of the Udmurt Kinesh Tatiana Ishmatova, who represents the ruling United Russia party, called his positions “without compromise, sometimes reaching the point of radicalism.” Alexander Brechalov, the head of Udmurtia, called on journalists “not to speculate on the topic of ethnicity.”

Meanwhile, the local branch of the Investigative Committee is investigating Razin’s death as a suicide. Razina and her daughter Sofi told The Moscow Times they have been questioned about whether his domestic life drove him to it.

They and others who were close to Razin believe he should be considered an Udmurt hero and have a different view about what was behind his choice of self-immolation as an end.

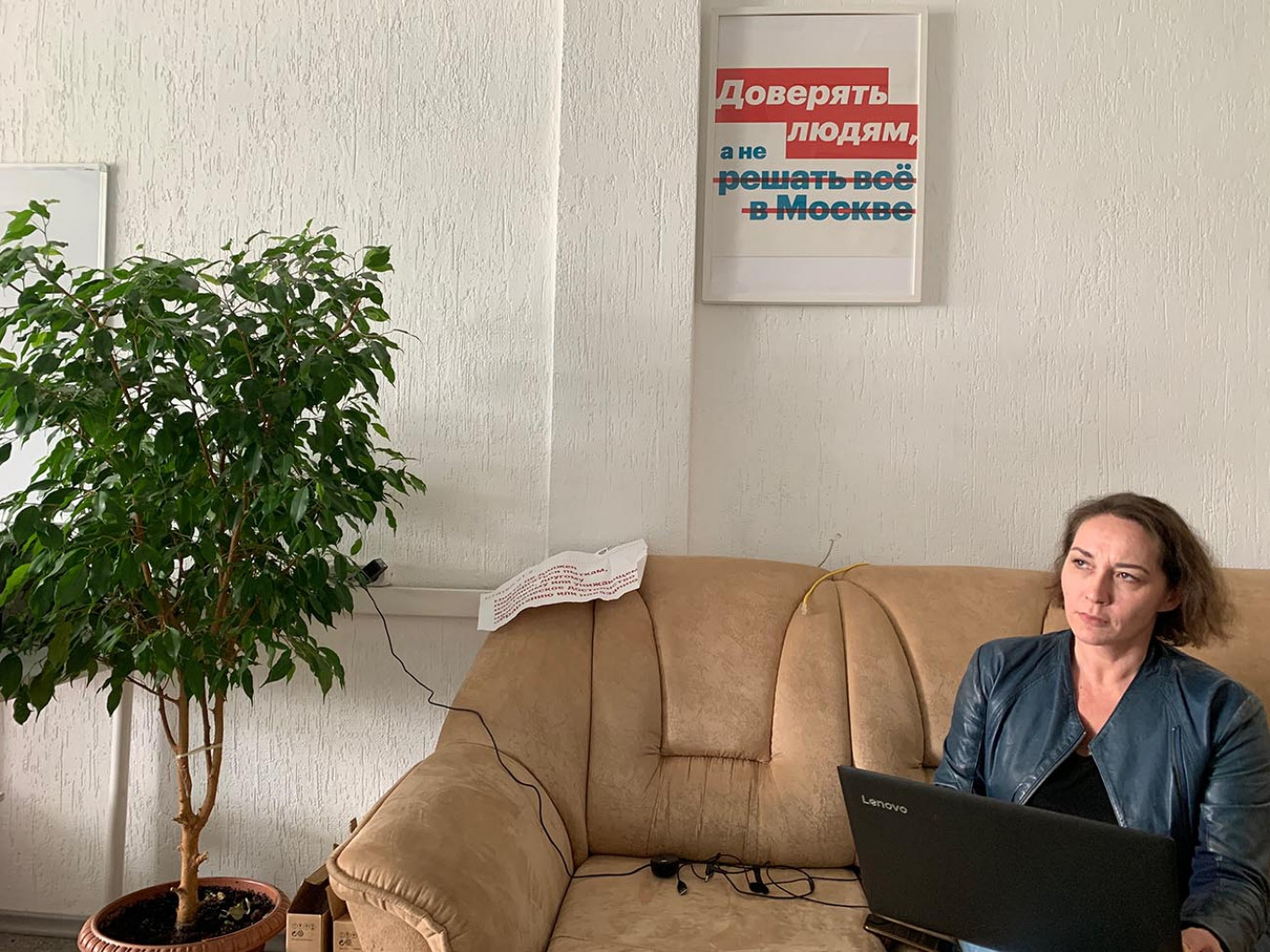

“It’s ultimately about the structure of the country,” said Rezeda Abasheva, the coordinator of opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s offices in Izhevsk. “We have a federation, but in actuality it’s an empire, with everything centralized in Moscow — authority, budget and now culture too.”

Activist Shklyayev believes that the Kremlin would rather see one unified identity across the country than the many that exist today to limit the potential for “color revolutions.”

He pointed to a law signed by President Vladimir Putin last year making the learning of co-official languages voluntary and highlighted a recent quote from the head of the Federal Agency for Ethnic Affairs: “It is the Russian language that unites all of Russian society and the entire Russian world.”

Alexander Verkhovsky, the director of the Moscow-based SOVA Center, which tracks extremism, disputes Shklyayev’s view. “It’s not about combating extremism,” he said. “It’s time-consuming and expensive to enforce mandatory teaching of all these languages.”

“Officials would rather just concentrate their resources elsewhere, even if they are shirking their responsibilities,” he added.

Larisa Buranova, Udmurtia’s ethnic affairs minister, argues that she and Razin actually had the same aim, even if they were often at odds with one another.

“My door was always open for him,” she told The Moscow Times. “We just disagreed on how best to go about preserving Udmurt culture. And while I get a lot of flak for this, I believe you can’t force people to learn a language; we have to make it fashionable for young people so they fall in love with it.”

As those close to Razin have replayed his final months and days, they have seen, in retrospect, signs of what he was intending to do.

Last summer, Razin handed his role as head of Udmurt spiritual life, a position that is typically held for life, to one of his supporters, Nikolai Mikhailov.

At the end of this summer, Yulia Razina noted that he threw out his sandals, saying he would no longer need them.

And Sofi Razina said that on the morning of his death, she found two chocolates on her window sill. He had given her just one a day to have as a treat with her tea since she was a little girl.

Minutes before Razin burst into flames, he gave a video interview to Perevozchikov in front of the State Council. “The Udmurt ethnos is vanishing, and I can’t look at that indifferently,” Razin says in the video. “Decisive steps must be taken.”

As well as being Udmurtia’s capital, Izhevsk is also the birthplace of the AK-47 rifle. On Thursday, Putin visited the city to honor what would have been its inventor Mikhail Kalashnikov's 100th birthday. He did not mention Razin in his comments.

In an echo of the murder of opposition politician Boris Nemtsov in Moscow in 2015, activists have been laying flowers and Razin’s portrait at the spot of his death every morning, only for them to later be removed.

One reminder, however, hasn’t yet been erased. Next to the spot where the tributes appear every day, a dark circle remains, burned into the pavement.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.