An aging leader steps down as president but keeps a firm grip on the reins of power. For many in the Kremlin, the choreographed events unfolding in neighboring Kazakhstan are a model for Russian President Vladimir Putin to consider.

Unlike his Kazakh counterpart Nursultan Nazarbayev, however, nobody’s certain Putin could pull off a transfer of power without triggering infighting among rival Kremlin camps that currently are held in check by his rule. The political and personal risks to Putin are high.

A transition similar to the one under way in Kazakhstan has been actively discussed in Moscow, said Andrei Kolyadin, a former presidential administration official who now works as a political consultant for the Kremlin. “The Nazarbayev scenario could suit the political elite, who want an arbiter who can influence the process after the successor takes over,” he said.

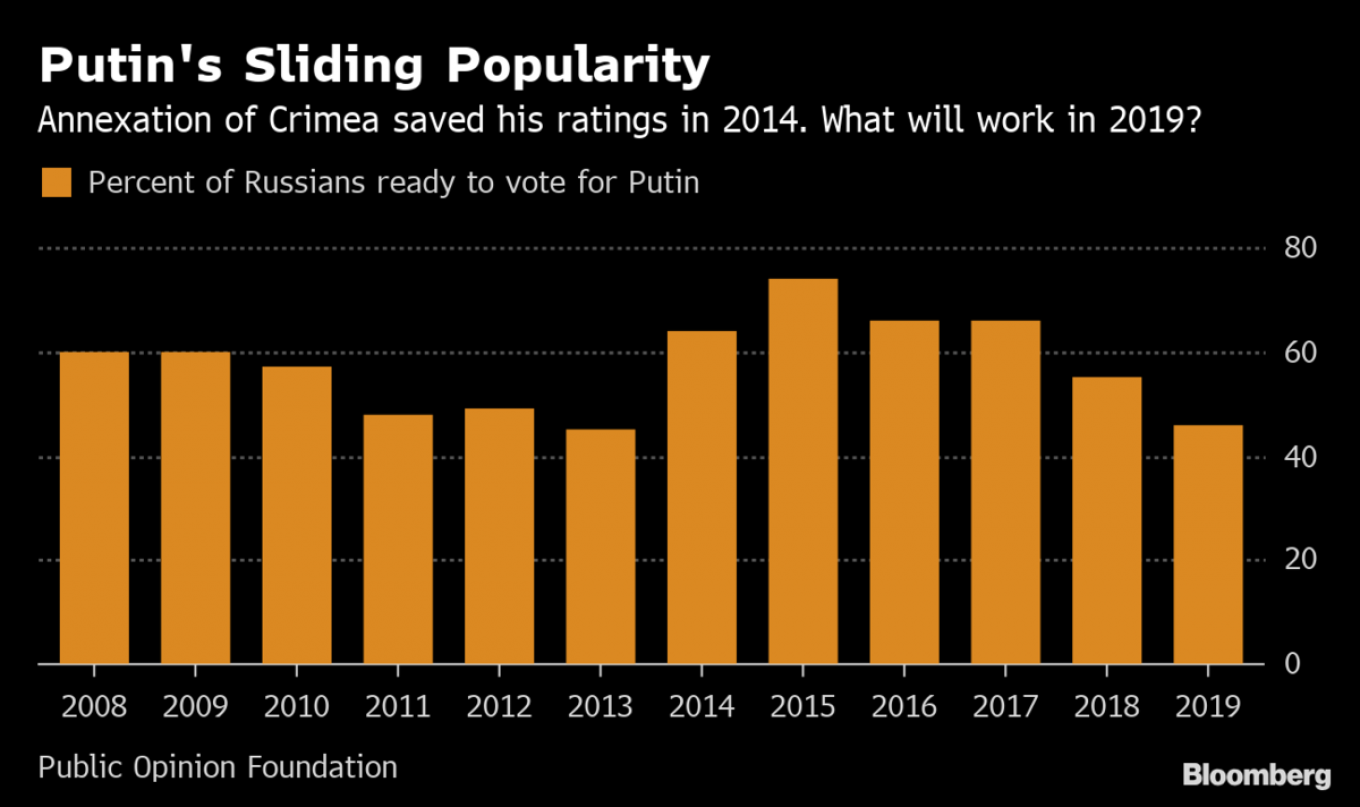

This week’s decision by Nazarbayev, 78, to hand the presidency to a trusted ally, while retaining key powers as Kazakh security council chief and leader of the nation for life, has thrown the issue into sharp relief. Putin, 66, won a fourth and presumably final term with a record 77 percent in elections last year. He’s crushed political opposition and centralized power in his own hands since he was first elected in 2000, becoming so dominant that many Russians find it hard to name potential successors even as his popularity has declined.

Putin, whose term ends in 2024, hasn’t anointed anyone as his heir, while saying repeatedly that he won’t change the constitution to extend his rule. That didn’t stop Vyacheslav Volodin, the speaker of Russia’s lower house of parliament, raising the possibility of constitutional reform in December.

New state

Some within the ruling elite are pressing the Russian leader to remain president for as long as possible, three people close to the Kremlin said, who had asked not to be identified. Options being explored include pressing neighboring Belarus into uniting with Russia to create a new state so that Putin can sidestep constitutional term limits. There’s no agreed scenario for a transition, the people said.

Even so, “Putin can’t stay on forever — he’s mortal,” said Olga Kryshtanovskaya, a sociologist who studies Russia’s ruling elite at the State University of Administration in Moscow. “If he doesn’t prepare the ground for succession it will end badly. Everyone will be at each other’s throats.”

Putin already once engineered a handover of the presidency to his protege Dmitry Medvedev to comply with the constitutional ban on more than two consecutive terms. Medvedev was president from 2008-2012 and Putin took over his role as prime minister, continuing to run the country until he returned to the Kremlin after four years.

Transfer powers

This time, Putin could transfer key presidential powers to the security council or an advisory body called the State Council, both of which he heads now, then use them to exercise influence once he leaves the Kremlin, according to political analysts in Moscow.

The Kremlin will monitor how much control Nazarbayev exercises in Kazakhstan and how power gets redistributed under the new arrangement, said Alexander Baunov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center. Russia and Kazakhstan have “a similar economic structure and type of authoritarianism,” he said.

Still, there are doubts whether Russia’s feuding elites would continue to respect Putin’s authority if he handed the presidency to someone else, said Sergei Markov, a political consultant to the Kremlin. While Kazakhs may allow Nazarbayev to be a mentor figure like Singapore’s founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, “in Putin’s case, if he left, he would face an immediate challenge,” he said.

It’s impossible to repeat Nazarbayev’s strategy because the Russian political system is more complicated than the Kazakh one, said Arkady Dubnov, a political expert based in Moscow who specializes in central Asia.

Protect legacy

The election of Nazarbayev’s eldest child, Dariga, as the Kazakh Senate’s new chairwoman on Wednesday, which puts her first in the line of succession to the presidency under the constitution, is an example Putin has signaled he’s unlikely to follow with his own daughters.

Resistance in Belarus to being absorbed by Russia also makes it hard for the Kremlin to pursue the option of Putin leading a new state, said Kryshtanovskaya.

Already the longest-serving Kremlin leader since Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, Putin will face increasing pressure to protect his legacy as the clock ticks down on his fourth term. The former KGB officer may find himself caught between a desire to preserve political legitimacy by making way for a successor and the challenge of keeping control of the system of power he’s built up over nearly two decades.

“Putin can only envy” Nazarbayev’s actions, Dubnov said. “It won’t work for him.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.