A comprehensive retrospective of Aristarkh Lentulov, one of the most important figures in the Russian avant-garde movement, opened at the Bakhrushin State Central Theater Museum a week ago. Devoted to the artist’s 135th anniversary, it encompasses works from all periods of his life, from the turn of the century to the 1940s.

The exhibition presents 250 artworks from 20 museums around Russia and 11 private collections, including the artist’s great grandson Fyodor Lentulov. It’s the first exhibition of Lentulov’s work of this scale in 30 years, and it was organized in record time: just four months and two weeks.

The title of the exhibition, “MysteryBouffe,” refers to the play by Russian avantgarde poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. The author himself called it “the revolutionary road” and set the tone for much of post-1917 art. Although Lentulov did not design the stage sets (they were developed by Suprematist avatar Kazimir Malevich), the idea of a “mystery-bouffe” or comic opera reflects his ideas about art. Mayakovsky used to say that what he did with literature, Lentulov did with art.

Born into a poor priest’s family in a small town 100 kilometers from the central Russian city of Penza, Lentulov studied art in Kiev and St. Petersburg before moving to Moscow in 1909. He was one of the founders of the Jack of Diamonds, a group of Moscow avant-garde artists that included turn-ofthe-century greats like Malevich, Robert Falk, Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova.

Although one of the major figures in Russian avant-garde movement, Lentulov found inspiration in lubok (Russian popular prints), store signs, icons and ancient Russian architecture. Lentulov also had access to the Western art collections of pre-revolutionary entrepreneurs Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, so you can see some allusions to Van Gogh, Gauguin and early Matisse.

“We wanted to show how he changed various styles: Behind every painting exhibited here there’s a whole group of similar works that we are just not able to show,” says Svetlana Dzhafarova, the exhibit’s curator. Lentulov’s paintings show the influence of styles including Cubism, Primitivism, Fauvism, Expressionism and Futurism. He was a painter who liked to play with light.

“He’s most interested in how nature changes due to different light, different positions of the sun. Later he started painting theater floodlights for the same reason. It’s his justification for the transformation of reality that we see on his paintings,” says Dzhafarova.

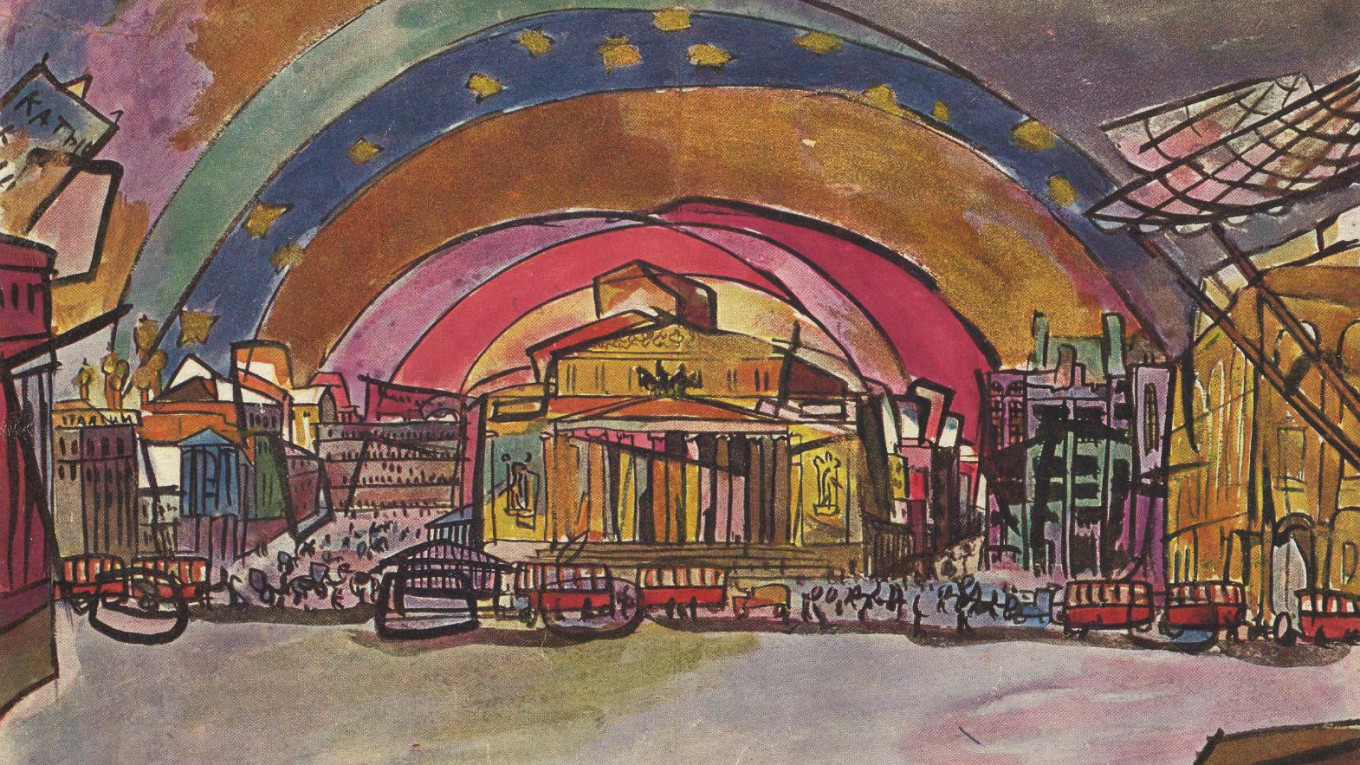

Since it is being held at a theater museum, the exhibition draws parallels between Lentulov’s paintings and his works for theater— stage sets and costume designs. This allows us to see the close connections between the two artforms in the first few decades of the 20th century.

“He had a certain theatricality in all of his works, even those that had nothing to do with theater,” says Dzhafarova. Russian theater in the early 20th century was different from that in Europe, because Russian theaters started inviting high-profile professional painters to produce backdrops, rather than ordinary set designers.

About 70 costume and stage decoration sketches for 10 theater productions are exhibited, including “Hoffmann’s Fairytales,” “Stepan Razin” and the model of the set for Lermontov’s “Demon,” for which Lentulov received the Diplôme de Medaille d’Or at the Paris International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925.

With time, Lentulov started using decorative elements in his paintings, too, gluing on bits of fabric and pieces of embroidery, or using bronze, silver and even gold paints. This is especially true for his female portraits. One of his favorite subjects was his wife, Maria Petrovna, whom he painted in different outfits and at different ages. Several of these portraits are at the exhibition, including Maria as Venetian socialite Luisa Casati, as well as a Cubist double self-portrait in which he poses with his wife both en face and in profile.

Lentulov liked to paint monasteries. At the exhibition you can see a series of paintings depicting the New Jerusalem monastery complex and the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius in Sergiev Posad, as well as a monastery in Nizhny Novgorod and the Strastnoi monastery in central Moscow, torn down in the 1930s.

During the Soviet era, Lentulov turned to Social Realism. Dzhafarova explains this by his tendency to follow the latest trends in art: “It’s not like it only happened in Russia. Avant-garde vanished in Europe, too and not because it was destroyed by the government.”

His paintings from this period include canvases depicting the building of the metro, new constructivist architecture and factories.

“Lentulov was inspired by industry,” adds Dzhafarova. “You can’t paint something like this artificially—he was a very organic artist.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.