On May 10, an unusual post appeared on Facebook, apparently signed by Viktor Ivanov, the head of Russia’s Federal Drug Control Service (FSKN). “Comrades and fellow soldiers,” it began. “I want to apologize that I couldn’t save our organization. We protected our national interests honestly.” Someone somewhere seemed far from happy with the decision to dismantle one of the largest government agencies.

For any former senior level official to question President Vladimir Putin’s logic is, in the context of the Russian system, a demonstration of significant disloyalty. The post — allegedly written by Ivanov himself — disappeared from Facebook within an hour. The FSKN press office described the publication as a “provocation” against the service and its head.

The decision to disband FSKN, along with the Federal Migration Service, was announced on March 30 as part of a broader reform, including the creation of a new National Guard. Under the plans, in little over one week, the agency will be no more, and Ivanov, a longtime associate of Putin, will retire. According to various sources in and around government, Ivanov had been kept in the dark about the plans until the very last minute.

This is a quite unusual way of doing business in Putin’s universe, and seems to be a sign of serious dissatisfaction somewhere within government.

The Power Broker

Ivanov’s name features prominently in any account of Putin’s rise to power. A career KGB officer, he moved to St. Petersburg in the 1990s to take up a role within the city administration. According to some reports, he did this on Putin’s own recommendation. Since then, their careers have dovetailed. When, in the late 1990s, Putin headed the Federal Security Service (FSB), the successor to the KGB, Ivanov was assigned a top position in the service.

Ivanov always dealt with paperwork, not fieldwork, a former official who knew him at that time recalls. “He was always the HR manager,” he says.

When Putin was elected president, the “HR manager,” albeit with KGB roots, enjoyed a meteoric rise to become presidential deputy chief of staff. This was a position of enormous authority. It placed Ivanov in charge of the Kremlin’s HR department, and gave him control over all issues relating to national awards and staffing within the justice system. It was here that he developed a reputation as the Kremlin’s forceful power broker — alongside and together with Igor Sechin, a similarly faithful assistant hailing from Putin’s St. Petersburg days.

The extent of Ivanov’s omnipotence was publicly revealed in court in 2008, when a leading Supreme Arbitration Court judge testified that Ivanov’s staff directly intervened in judicial appointments. This is unconstitutional. One of Ivanov’s former colleagues agreed that “of course” this was what was happening — “but this is how the system works, they were acting in the interests of the state, and besides, it has only gotten worse since.”

It was around this time that Ivanov’s rise was checked and his career problems began. He first ran into Dmitry Medvedev, who became president in 2008, and who found it difficult to deal with Putin’s KGB associates. Ivanov was asked to move out of the Kremlin, and, in a clear demotion, he was transferred from his top position within the presidential administration to become head of the new Federal Drug Controls Service.

Breaking the Golden Rule

The idea for creating a special federal agency for drug control came from another of Putin’s St. Petersburg security associates, Viktor Cherkesov, in 2002. It was largely modeled on the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration created in the early 1970s to fight drug smuggling.

The idea of creating the new agency came naturally enough. The drug threat had, by the early 2000s, become very serious, with Russia forming a huge market for opiates coming from Afghanistan and Central Asia. As a former security services official says, the Interior Ministry was simply unable to deal with the inflows due to their own involvement in drug trafficking. The new agency was given priority resourcing: 40,000 officers, all necessary operational hardware and, more importantly, the authorization to use it. The FSKN wiretapping department gained legendary status.

“Their investigators were given a full forensic set of their own and didn’t need to stand in line to get it,” explains one former FSKN official. “This was quite a big deal.” Every Russian law enforcement agency has a natural inclination to look to expand authority and their areas of control, and the FSKN was no exception. As the years past, they began to prosecute businesses that had little to do with trafficking but dealt with, for example, industrial drugs or chemicals. They targeted veterinarians, industrial chemistry entrepreneurs, and even bakers producing poppyseed muffins.

The tale of Cherkesov’s eventual downfall began in August 2000, even before the FSKN was formed, when Russian customs seized a furniture shipment on the charge of falsifying its weight and price. This apparently routine operation turned into an epic years-long struggle within Russia’s corrupt security clans once it transpired that top FSB officials were involved. Several people were killed and dozens arrested in relation to the case.

Putin tasked his then-trusted lieutenant Cherkesov with securing surveillance and criminal evidence, something the FSKN was famous for. But the operation did not go to plan, as highly influential players have been hurt. In 2007, several of Cherkesov’s FSKN officers were arrested on the grounds of obtaining illegal surveillance in the furniture case. Cherkesov responded to the arrests by publishing an accusatory and highly revealing op-ed in Kommersant newspaper.

But by doing so, he broke Putin’s number one rule: Never air your dirty linen in public. Within the space of a few months, Cherkesov was dismissed and Ivanov had taken over the helm of FSKN.

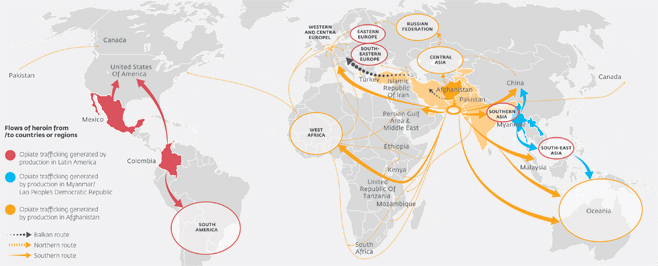

Main Global Trafficking Fows of Opiates

View the map in higher resolution here.

Spanish Inquisition

Eight years on, FSKN itself is soon to be no longer, and now it’s Ivanov’s resignation that doesn’t look entirely honorable. Until recently, Putin was always known for his care of his close associates. He never threw his advisers to the street — least of all, his longtime security service associates. But now Putin seems to be in the process of revising his own approach. Getting rid of old friends is no longer such a problem.

The switch was evident a few months ago with the rough dismissal of the head of Russian Railways Vladimir Yakunin, a former KGB officer and longtime loyal aide. “It’s as if Putin’s old guard finally lost immunity after what happened to Yakunin,” says analyst Alexei Makarkin. “Putin has turned to purging his inner circle. Now he kicks people out without thought or compensation.”

The disbandment of FSKN was presented to Ivanov as a fait accompli. He was offered a deputy minister of interior position, but was given short shrift when he refused. “He tried to reach out to Putin, failed, and now has no other option but to retire,” a source says.

Different power and security state institutions continue to fight each other for their place in the sun. Russian security is in many ways like a snake biting its own tail, sodden in corruption and racketeering. The line between Russian law enforcement, the state and organized crime is becoming increasingly difficult to draw.

Putin’s dissatisfaction with Ivanov may have derived from a scandal that took place thousands of kilometers away in Spain, Makarkin says. In early May, a Spanish judge issued international arrest warrants for 12 Russians suspected of organized crime including Nikolai Aulov, the deputy head of FSKN and Ivanov’s close associate from the 1990s.

“Aulov has a very bad reputation even within the law enforcement community,” says Roman Anin, a Russian investigative journalist. “All those who know him are highly allergic to his name,” Anin adds. Phone conversations tapped by Spanish prosecutors suggest he was close to Gennady Petrov, a top Russian mafia boss.

Speaking to the Guardian earlier this year, Ivanov confirmed that Aulov, his deputy, had been in regular contact with Petrov. “Petrov provided [to Aulov] operationally useful information on a number of topics. The rest is made up,” the paper quoted Ivanov as saying.

Regardless of the denials, the warrant for Aulov’s arrest was embarrassing for Ivanov. “It’s absurd,” a former FSKN official says. “How can somebody wanted by Interpol for links with the mob hold a top position at a special service specifically designed to fight the mafia?”

Anin says that the Aulov problem could plausibly have affected Ivanov’s fate. The recent Western crackdown on criminal groups with Russian links has certainly set alarm bells ringing within Russian establishment. Putin may now be motivated to be harder and more scrupulous toward his longtime associates.

Complete Annihilation

Analyzing the real efficiency of Russian law enforcement is an impossible task. High levels of secrecy limit the information on offer, while official statistics are usually subject to various tricks and manipulations. During its years of existence, FSKN was no exception in this regard, and it is hard to properly assess its record.

Nonetheless, the controversial anti-drugs activist and current mayor of Yekaterinburg Yevgeny Roizman says that the FSKN proved its worth as a competent authority. The amount of heroin smuggled into Russia has begun — finally — to decline, he says, and that is thanks to their activities.

Most experts and insiders surveyed by The Moscow Times agreed that the liquidation of FSKN is a risky call, and the situation with drug trafficking will deteriorate. Roizman believes the agency kept other government ministries on their toes. “There will be less competitiveness,” he says. “The FSKN and the interior could never come to terms and always tried to let each other down. Now the interior will know nobody is after them.”

With the Russian economy shrinking for a third consecutive year, and the fighting among law enforcement clans intensifying, the FSKN was always likely to be a target for restructuring. Indeed, Ivanov apparently rebuffed an attack at his agency last year, when the press leaked that a decree to liquidate FSKN had been already sent to the government. This time, as the Facebook post on May 10 said, Ivanov just couldn’t save it.

Come June 1, nothing will remain of the former agency. “Not one FSKN general will move over to the Interior Ministry,” says the source

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.