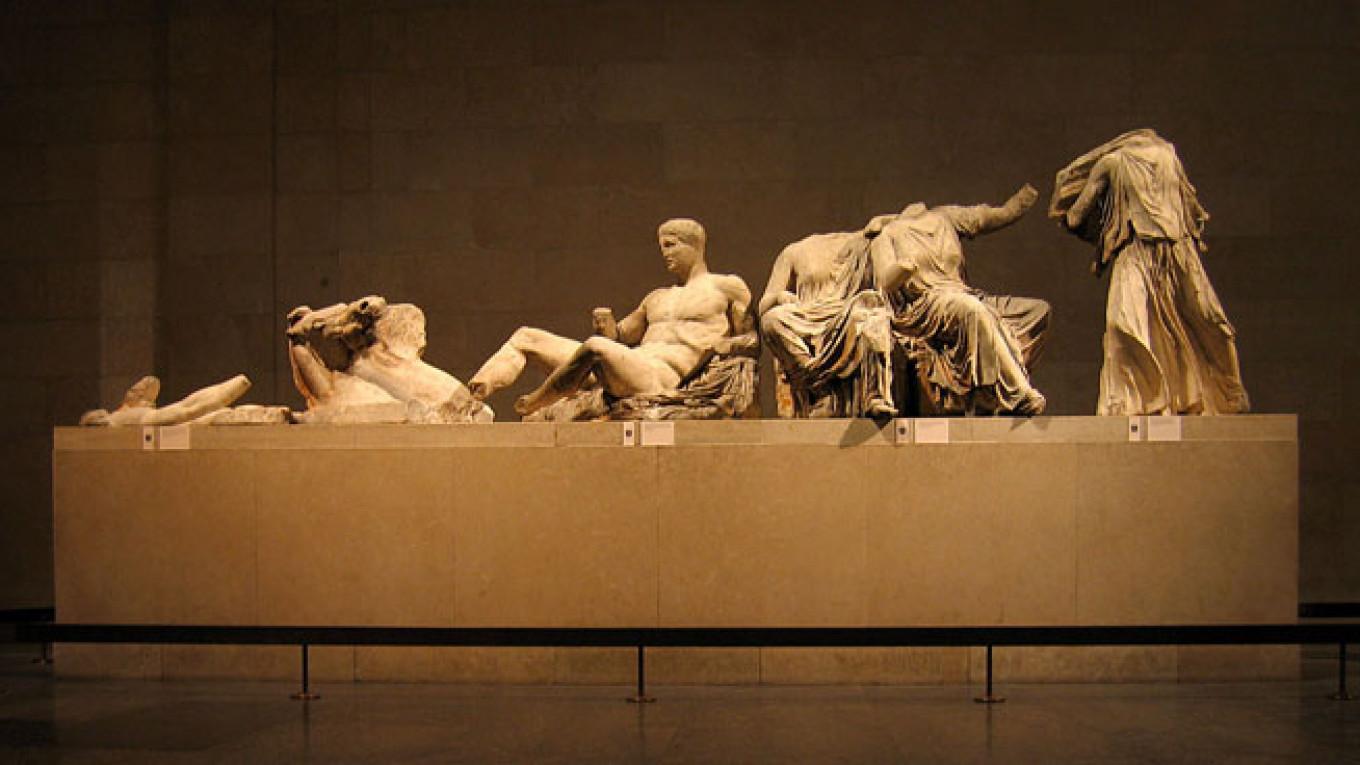

While the West is eager to punish Putin over Ukraine, many were outraged when the British Museum decided to lend Russia one of the most esteemed vestiges of Western art and civilization: the Parthenon marbles. The British Museum announced its loan of the statue of Greek river god Ilissos to the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, marking the first time any of the British Museum’s collection of the marbles has left Britain.

The debate since then has settled into a now familiar set of arguments over which country has legal and moral sovereignty over the object’s display.

Controversy has followed the marbles since Thomas Bruce, seventh earl of Elgin, claimed in 1811 to have obtained a permit to remove the classical Greek marble sculptures from the Acropolis in Athens. They were purchased by the British government and passed to the British Museum. Greece has long lobbied for the restoration of the country’s monuments, and this year UNESCO agreed to mediate the dispute between Britain and Greece.

The controversy was revived after the artwork was flown to St. Petersburg.

While British Prime Minister David Cameron shrugged the whole thing off, saying it was a move made by the museum’s board, London Mayor Boris Johnson was quick to praise the move, calling the statue “a marble ambassador of a European ideal.”

Yet whatever one thinks of the morality or legality of the British Museum’s decision, it is a mistake to minimize the potential for art to play a role in cross-cultural negotiations and political dialogue.

The very concept of cultural property as we know it today has roots in the long tradition of object-collecting in Britain. By the mid-18th century, an estimated 40,000 elite Englishmen had taken the habit of traveling Europe, captivated by classical Greek and Roman ruins.

But all this object-collecting was also intimately weaved with national identity. By the 19th century, burgeoning nation-states were treating art objects as cultural capital, and museums raced to augment their collections.

When Lord Elgin took the marbles, he was thus exercising two British ideas: that cultural vestiges can belong to anyone at all, and that, by later giving the marbles to the British Museum, he was contributing to bolstering Britain’s cultural capital.

The British Museum’s loan of the statue to the Hermitage carries a powerful political message, at a time when Western relations with Russia are at their lowest ebb in 30 years. The loan is being made in 2014, which is the bilateral U.K.-Russia year of cultural exchange.

During a year of strained relationships, artists, curators and museum directors in both Russia and Britain are working hard to continue to develop new, creative and contemporary narratives in both countries.

The dispatch of the statue is a reminder that there are areas where the interests of Russia and the West coincide — in this case, the appreciation of art and a sense of the common fate of Europe against a deeper historical background. The Greeks are rightfully indignant to see a part of their heritage jetting across Europe, and they can be emboldened by the argument that allowing the statue to leave London weakens the British Museum’s case for keeping the marbles, since the museum had long argued that the marbles were too fragile to be moved.

The British Museum’s decision raises a broader question: Should art be used for political purposes?

One thing’s certain: The Ilissos, treated as cultural property with profound worth to a nation’s identity, stands as a fraught relic of how art and objects cannot escape their role in forging national identity and policy in a global society.

Aria Danaparamita is the author of a study of the excavation of the Borobudur statues at the British Museum and Jennifer Tucker is a professor of modern history at Wesleyan University.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.