In the quasi-religious personality cult surrounding Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, the leader's death mask became for many the Holy Grail — second, perhaps, only to the mummy that still resides on Red Square. The relic, supposedly one of three originals cast by sculptor Sergei Merkurov, is now up for auction through a Boston-based dealer, which estimates it will fetch $35,000-$40,000.

But 90 years after Lenin's death led to a brutal competition for succession, the mask continues to stir up controversy. The sculptor's family has vowed to stop the online auction, which concludes on June 18, saying it is illegal. Beyond their complaint lies a greater question: is the mask even real?

On the frosty night of January 21, 1924, Merkurov was summoned to the estate of Gorky, where Vladimir Lenin had just died after suffering his final, fatal stroke, to preserve the leader's visage. Merkurov, legend has it, initially cast three plaster masks of Lenin's face. The first mask went to the Central Lenin Museum, the second went to the Gorky estate, and the sculptor kept the final mask for himself.

It is this last mask, RR Auction says, that was eventually sold by a member of the family to an agent in the U.S., where it was acquired by the well-known Russian collector Sasha Lurye, and then resold to another private collector.

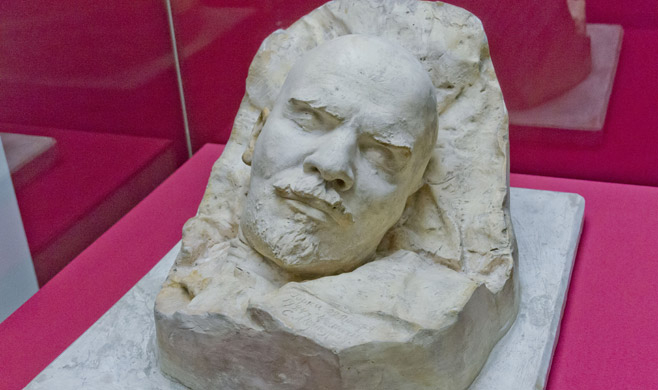

Beyond some chipping around the eyebrows and a weathered patina that apparently testifies to its age, a photograph on the auction house's website reveals the mask to be in fine condition, with the famous signature "Gorky, 22 January, 1924, 4 a.m., S. Merkurov" visible below Lenin's cheek on the right-hand side.

The story, however, quickly gets murky.

Lenin bust from melted down bells.

To mark Lenin's funeral, the sculptor made 14 masks to distribute to members of the Soviet elite, including secret police chief Felix Dzerzhinsky. But Merkurov, who authored dozens of monumental Lenin and Stalin statues across the Soviet Union, was "clever," says death mask historian Dmitry Shlyonsky.

"It seems that he kept a mold with which he would from time to time cast new masks, passing them off as originals," he said.

After World War II, for example, Merkurov made a Lenin statue for Lviv, and awarded the death mask to the city as a gift. A copy of it now resides in Shlyonsky's One Street Museum in Kiev.

"Today, many sculptors still have casts from copies of masks," Shlyonsky said. He said the mask currently up for sale could be one of the originals, but could just as easily be a copy made in the 1950s.

A possible clue to the mask's origins is provided by the death mask held in the Central Lenin Museum, now the State Historical Museum. For decades, the mask was the emotional culmination of the museum's display dedicated to Lenin's funeral, when hundreds of thousands of Soviet citizens lined up to see his body lying in state. Today, it lies on red cloth in its own spotlit glass case.

While at first glance, it appears identical to the mask now on sale, closer examination reveals a subtle difference: the faint inscription "21/I/1924" on its left-hand side. According to museum researcher Olga Grankina, when copies were made of the originals, this date did not show through, as the inscription was too shallow.

The mask was previously put on the auction block by U.S. dealer Historical Archives in 1999. A story in The Moscow Times cited an official at the St. Petersburg department for the preservation of cultural valuables, who confirmed that the department had given permission for the mask to be exported.

While Kommersant newspaper optimistically placed the mask's potential value at $250,000 to $500,000, Historical Archives' Jack Reznikoff said it sold for $30,000 to a private collector.

On show in Moscow, one of the three masks that Merkurov made in 1924.

"It is certainly worth a lot more," he said. "A Lenin autograph, which is very rare, usually sells for $20,00 or $30,000 but there's dozens of them out there."

Reznikoff says he has no doubt the mask is real. "A lot of relics, just by their nature, require a little bit of a leap of faith," he said. "The question is whether that leap is a crack in the sidewalk or the Grand Canyon."

Countless cultural artifacts were smuggled out of the Soviet Union to the West, many of which are now for up for grabs online. A quick scan of eBay reveals thousands of items connected to Soviet leaders, including a World War II-era rug bearing a portrait of Stalin.

Anton Merkurov, the sculptor's great grandson, says the death mask should not be bought and sold. "It is Soviet cultural heritage," he said. "Therefore, the sale is illegal." He said the family has put a stop to several previous attempted auctions.

Even though Anton Merkurov demands that the auction be canceled, Bobby Livingston, vice president at RR Auction, said the sale will go forward. "If something was improperly taken or stolen, then we believe those things should be returned, but when things are disposed of properly, there is a clear change of custody," he said.

Also on sale is a Lenin bust cast out of melted-down church bells, which Merkurov made in 1926, as well as a 1933 letter written by avant-garde film director Sergei Eisenstein. Vacationing in the Caucasus after shooting a film in Mexico, Eisenstein requests glossy magazines on art and cinema from abroad in the letter.

RR Auction has previously sold several death masks of famous Americans, including 1930s gangster John Dillinger and director Alfred Hitchcock. Dillinger's mask, a "second generation" edition, fetched only $700, Livingston said. As of Monday afternoon, the highest bid for the Lenin mask stood at $13,976.

"A piece of plaster, moreover one from who-knows-when, just is not worth that much money," Shlyonsky said.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.