Following Russia's military operation in Crimea, the subsequent referendum on March 16 and its annexation, Western politicians and commentators were quick to label the events as representing "19th-century approaches" to international relations. But unlike previous Russian military operations, the Crimea campaign was different. With its use of special forces, intelligence, information warfare and cyber-warfare elements, it was highly sophisticated.

Of course, there are elements of 19th-century thinking in Russian security and foreign policy, but this is actually overstated. In reality, Moscow's approach on these issues is far more complex than some Western commentaries would allow. In the Crimea crisis, President Vladimir Putin never questioned Ukraine's sovereignty. He did question the territorial integrity of the country and acted only after time and events unfolded. His silence after the downfall of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych is important. He was allowing time for assessment and analysis of the situation, and then he acted. When Putin acted, the response was very much 21st century. His objective was to use "military persuasion" to create an atmosphere in which foreign powers may accept a compromise. In fact, there is no evidence to support the idea that Putin acted in anger.

Putin saw the Maidan protests as part of a Eurasian crisis, not simply in its European context. Putin believes this is about Russia's role in Eurasia. But in military terms in Crimea, the Armed Forces used small numbers of well-trained and well-equipped special forces combined with an effective information campaign and cyber warfare. That is why it stands out.

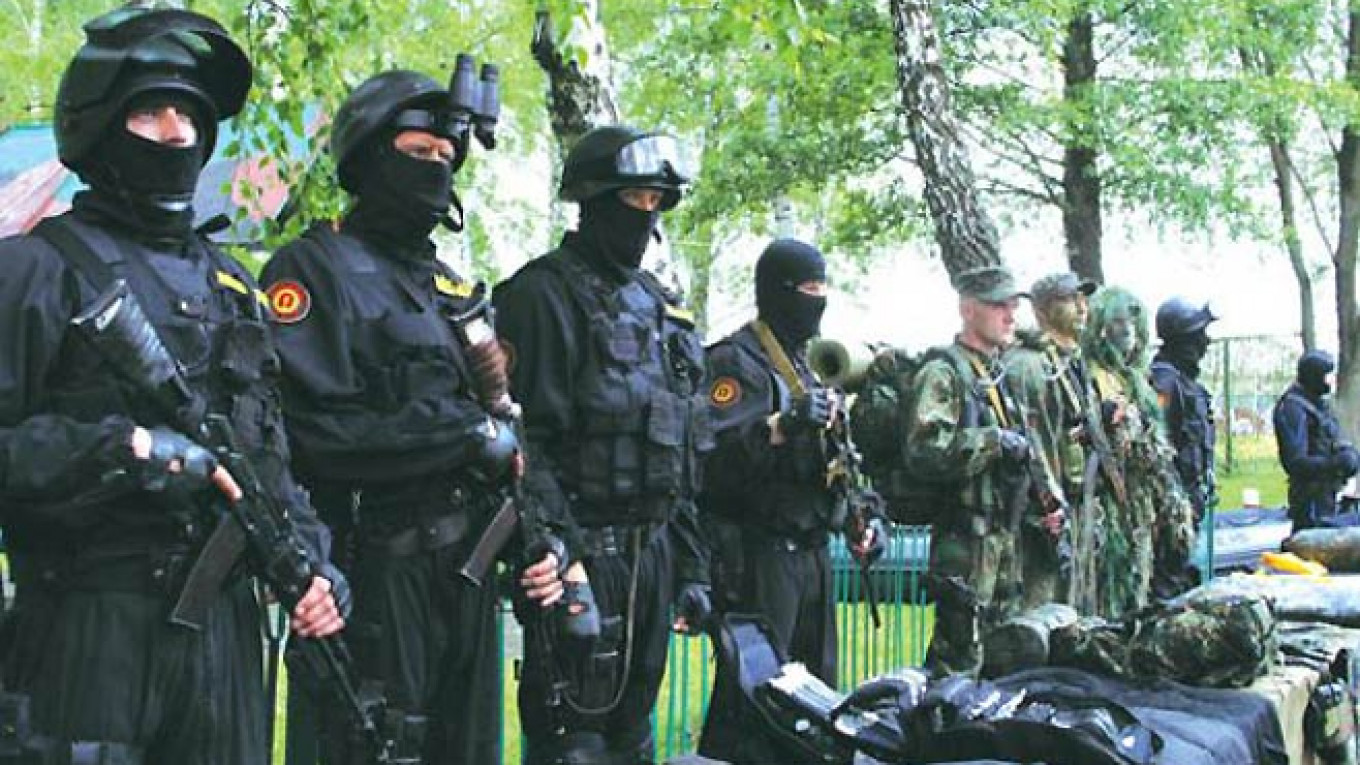

The military operation in Crimea appears to have tested the blueprint for Russia's new rapid-response forces. In this sense the operation reveals very little about the current condition of the country's Armed Forces. The rapid-response forces were to bring together specialist and elite units into an overall raid force projection capability. This centers on the airborne forces, special forces under Russian foreign military intelligence, naval infantry and three supporting Ground Forces brigades. Almost all of this force structure in terms of unit type was involved in the Crimea operation. But its real strength lay in covert action combined with sound intelligence concerning the weakness of the Kiev government and their will to respond militarily. Individual servicemen were highly disciplined and, more important, kept their fingers off the trigger.

It does not say much, however, about the wider condition and readiness levels in the Russian Armed Forces as a whole. But the Crimea operation does signal an intent to use military coercion as a foreign and security policy tool. The decision to act in the crisis is consistent with Russian security strategy and military doctrine. The Kremlin's view of the events in the Maidan differed fundamentally from a Western reading, and this combined with the fear of a Ukraine emerging as a NATO member in the future was too much for Putin. He evidently believed that he needed to act.

There are a large number of lessons from the five-day war in August 2008, but it remains unclear how many of them the Kremlin has incorporated. From these campaigns, Moscow learned fundamentally that preserving the pre-2008 military structure was nonsense. That old structure contained large numbers of so-called "paper units" with very few capable officers commanding forces only in theory. This was rooted in a mobilization principle that had died with the end of the Cold War. In its place, they tried to create smaller, "permanent readiness" units on the brigade model, but the problem remains mixing poorly trained conscripts with contract personnel, which limits their readiness and professionalism. Currently, the Defense Ministry plans to greatly boost contract personnel numbers over the next few years, but there is no sign of abandoning conscription.

The "snap inspections" are more about the style of leadership by Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu. They are fairly useless in practical military terms. The idea is to inspect combat readiness in certain units without advanced warning, but the tests are largely Cold War in style in that they measure how fast the troops can reach an assembly area. Its use shows that Russian commanders do not really know their men. But their use can also lie in the political domain, as we saw by exercising units within Russia in late February and more recently as the buildup took place close to the Ukrainian border. In short, these exercises can be used to cause anxiety on the part of Russia's neighbors.

Moscow appears to understand that any operation to grab land in eastern Ukraine would fundamentally differ from the Crimea operation in size, style and scope. The use of special forces in eastern Ukraine is to destabilize these parts of the country, orchestrate careful crisis control and to establish "escalation dominance." In other words, the triggers to escalate the conflict are in Moscow's hands.

The operational strategy and tactics used in Crimea depended to a large degree on the presence of a Russian base and others factors. Forces in the Southern Military District were on heightened alert and readiness because of the Sochi Winter Olympics. Russian forces were able to operate in a friendly, largely Russian-speaking environment, and Moscow knew, probably in great detail, the disheveled condition of the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

In this sense the operation could be difficult to replicate elsewhere, even if the political will exists in Moscow to attempt some economically unsustainable policy of land grabbing from neighbors. For example, the self-proclaimed Transdnestr republic is effectively cut off from a Russian military perspective, meaning it would be much more difficult to accomplish such an operation and largely depend on insertion by air. The same problems would be encountered in the Baltic states, but they have nothing to fear because Putin would never attack a NATO member.

The Crimea operation was unique, containing elements of old and new. The force mix was certainly new. But the key factors are as old as warfare itself: knowing the potential enemy, assessing his capabilities, gathering intelligence and exploiting the element of surprise. The Kremlin has "discovered" that small, elite forces, good intelligence and cyber-warfare capabilities used in the correct mixture brings success in military persuasion. Crimea, seen from Moscow's perspective, was a brilliant success, and at a strategic level Russian policymakers will draw upon the fact that nothing the West could have done would have stopped the annexation of Crimea. The implications of this will have a profound impact on the strategic calculation in Russia and maybe also within NATO.

Roger N. McDermott is senior fellow in Eurasian Military Studies at the Jamestown Foundation in Washington.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.