After four days at Tolstoy's country estate in Yasnaya Polyana, taking language classes and walks in the snow, I was on my way to the train station in Tula to go back to Moscow. I chatted with the young driver the hotel had hired for me about his car, his brother who went to college and had once been in Sweden, and then about where I was from.

"New York? Is beautiful?"

"Yes, and it's beautiful here, too."

Being an American middle-aged professor with teenaged children, I was used to asking hopeful questions, even if in my clumsy Russian: "In life what you want to do for work?"

"To drive cab."

I thought that over and said in confirmation: "To do what you do now."

He was 21. "Yes. I have achieved ambition." As far as I could tell, he was being neither proud nor resigned.

I nodded. "This is your own car?"

"Yes, my car. My family has this car." It was what we used to call a jalopy — loud, rattly, dirty vehicle, with hand-cranked roll-down windows and a front door that opened only from the inside. It reminded me of the beloved car I had when I was twenty-one.

I gave him a five-dollar tip, which I called a "propina," which is Spanish and then I in confusion said, "Nyet, nyet — vzyatka" (a "bribe" — which by the puzzled expression confused him more than propina), and he asked if I wanted help with my bags.

"No, thank you."

Exhilarated, the way some of us get when travel plans that have long made us anxious are working out perfectly, I strode in my snow-boots through the busy combo bus and train station and then, with thirty-five minutes to spare, in sight of the departure board, I planted myself over my two book-heavy bags. Books are cheap and good in Russia, and I hadn't been able to resist buying for a song quirky Russian volumes of Tolstoy scholarship. I reviewed the last several days — my arrival in Moscow, the train to Tula, my foggy-headedness during my Russian lessons with Yuliya, my happy long solo progulki, or strolls, through the wintry rolling farmland and woods, the tasty traditional meals at the little restaurant by the estate gates — and decided I had done okay, after all. I had been frustrated for a week by my hesitancy to converse, but I was gabby again. I knew I could get by in Russian.

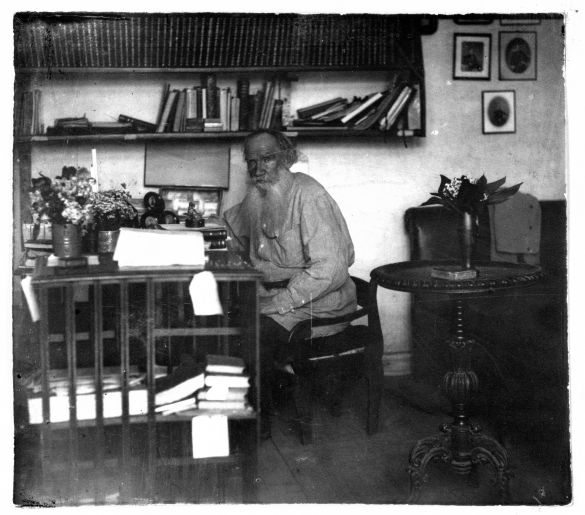

Tolstoy appearing contemplative in his Yasnaya Polyana study in 1908.

I listened for the track announcement. I didn't hear mine, but finally I noticed its listing on the board. Track 3! I took a breath and heave-hoed down the steps and through the connecting tunnel. I went up the stairs and coordinated one of the numbers on my ticket voucher with the number of the train. I greeted the uniformed woman standing at the top of the stairs — I had found the right car.

She did not greet me back but held out her hand as I stood on the first of the three steps. She wanted the ticket. I handed her the voucher I had printed out in Moscow. She looked at it and handed it back to me and said something dismissive. I took the next steps up and she yelled at me.

"This is the ticket," I insisted in Russian.

She refuted me and my ticket.

It dawned on me that I had read somewhere something — maybe back in New York when I had paid for it — that it was necessary to turn this voucher into a ticket; it wasn't required from Moscow, but it was required from everywhere else. Because that had seemed to me unreasonable — ridiculous, even — I had let myself forget that little detail.

But it would be no skin off her nose, I hoped, to let me stay on. The train was leaving in five minutes! But she was incensed at my stupidity — and appealed to another porter and a burly curious passenger her case for her belief in my blockheadedness. Even if you can't catch all the words you know you're being complained about.

"It's the same voucher!" I protested.

From the porter who wasn't yelling I understood that I had to go back to the station and exchange it for a ticket.

"Is there time?"

"No, probably not." He looked at his watch and doubtfully shook his head. Russians are wonderful at fatefulness; they don't have our American cheeriness that everything will work out.

I let out an anguished yelp and, hefting my bags down, I clomped across the platform, down the stairs, through the tunnel and up into the station in about sixty seconds.

There was a line of a dozen folks at the ticket window. I ran up to the window next to the one serving the line and shouted at the uniformed back of a woman I saw standing in the office.

"Please!" I called. She turned and glanced at me.

I pushed my voucher against the window. She ignored me and started to walk the other way! She called out something to someone and turned back around and proceeded slowly to my window.

I explained, "Ticket! My voucher — please to exchange — train go now!"

She looked at her watch. She shook her head and said, "Probably too late."

"Please!" I pushed my voucher and passport through the slot.

She made a face but read it. "Hm! You need ticket for this — to exchange."

"Yes, I know!"

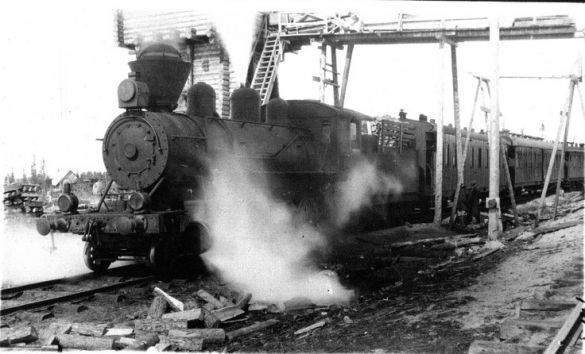

A train speeding through the countryside just after Tolstoy's era, in 1919.

She shrugged, took a gander at the trays on her counter, found a form, and filled it in with my information (even at such a moment, I loved seeing my name being rendered into Cyrillic), and then she stamped it, and then she turned it over and stamped it again, and then she looked at it a moment and only then did she slip it and my passport back under the window.

"Big thank you!" I yelled.

I re-schlepped my route at a lumbering jog. I was that stumbling panic-faced traveler you see every day at Penn Station or Grand Central.

Up the stairs, I saw the train and the steps were being pulled up from the platform and the door was closing — closed! I staggered up to it and banged it with my fist.

The woman porter opened the door and held out her hand for my ticket. She didn't lower the stairs but I hoisted my bags up and pushed them onto the landing and then pulled myself up by the handrail.

I had made it — and I was furious! (A year later, I wondered, what was the worst that could've happened if I'd missed it? Another night at Yasnaya Polyana!) I asked for my ticket back but without looking at me she held up her hand (did she know the expression "Talk to the hand"?) and continued examining the fresh ticket. Thank goodness it's really difficult to express one's anger in a foreign language!

When she shrugged and pushed the ticket at me I growled, "Thank you so much!"

She answered my sarcasm with the mild, multipurpose, "Pozhaluista!" which can mean "you're welcome"; "if you would …"; "please"; "no problem!" She had won that round too. I was now the idiot-passenger you see once in a while who's mad at an official who's only been doing her job.

I walked up the passage and found my cabin that I shared with two passengers, an older woman who nodded in greeting and then slept the next two hours to Moscow and the other, the middle-aged man who had witnessed my embarrassing first attempt to board the train. He got up from my berth and climbed to his above mine and offered me some of the buttered toast his old mother had made him for the first leg of his journey that would take him all the way to Vladivostok — further away from Moscow than my New York City is.

I apologized to him for the scene and my anger.

He blinked but didn't smile. "Pozhaluista."

He was a kind man.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.