The announcement that President Barack Obama is appointing Susan Rice as his new national security adviser, replacing Thomas Donilon, is unlikely to be welcomed in Moscow. As ambassador to the United Nations, Rice repeatedly clashed with Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov as she orchestrated and defended the NATO intervention in Libya.

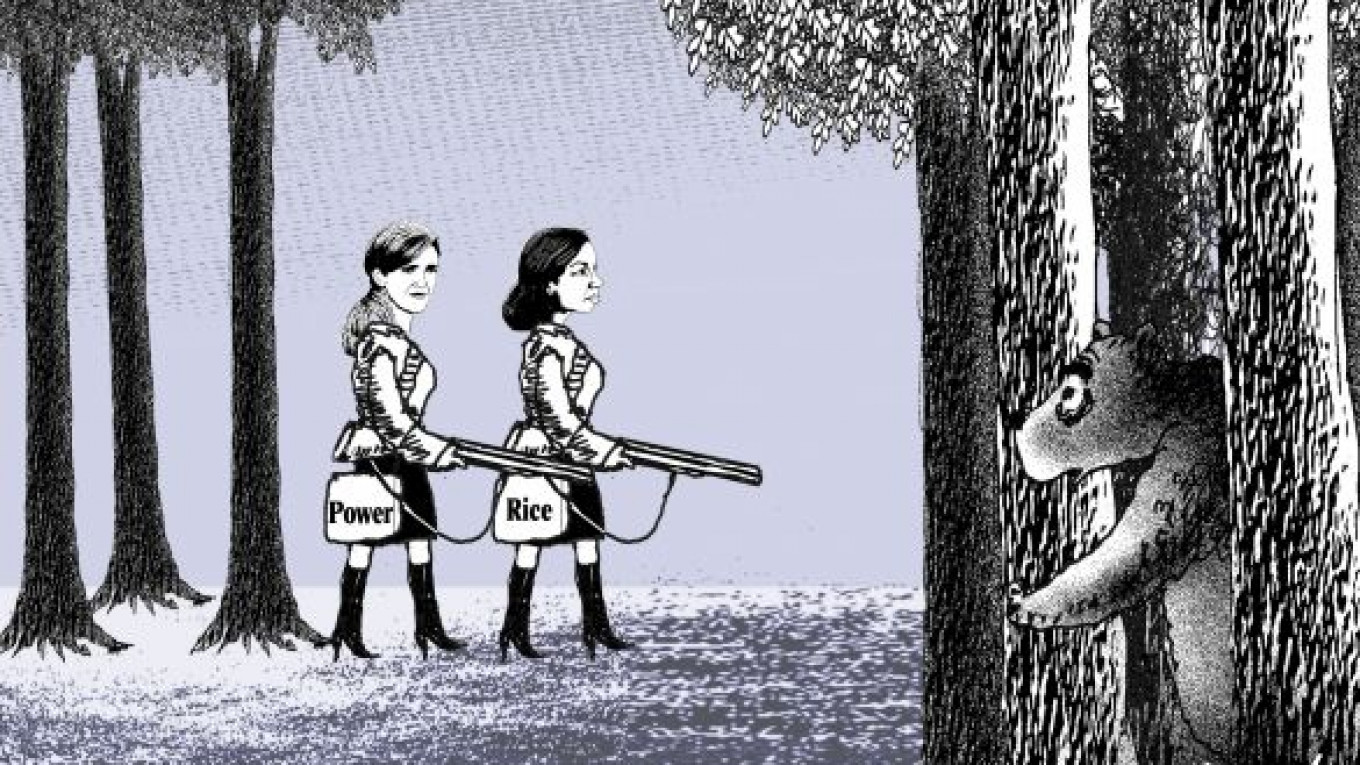

Rice's appointment, along with the nomination of Samantha Power as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, represents a substantial strengthening of the liberal, interventionist flank of the Obama administration at the expense of the pragmatic, realist camp. This suggests that U.S.-Russian relations, already at an all-time low in the wake of the U.S. Magnitsky Act, are unlikely to warm up anytime in the near future.

With Susan Rice's appointment as national security adviser, U.S.-Russian relations, already at an all-time low, are unlikely to warm up anytime soon.

Rice, 48, was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University and wrote her Ph.D. on the peace process that ended the war in Rhodesia. A protege of former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright — no friend of Russia — she served as a staffer on the National Security Council during the first administration of former President Bill Clinton, then as assistant secretary of state for African affairs during the second administration. She oversaw a policy of strong U.S. backing for new leaders in Uganda and Rwanda — leaders who subsequently invaded the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the name of preventing genocide but ended up fighting each other. She worked at the Brookings Institution during former President George W. Bush's presidency. In 2008, she defected from the camp of presidential candidate Hillary Clinton to join Obama's presidential campaign and was appointed UN ambassador in 2009.

During her five years at the UN, Rice was combative but not particularly effective. She developed a reputation for sharp elbows and a caustic tongue. In February 2012, Rice described Russia and China's veto of a UN Security Council resolution calling on Syrian President Bashir Assad to step down as "disgusting". Rice's television comments after the Benghazi attack on the U.S. Consulate there sunk her chances of being appointed secretary of state for Obama's second term since Republican senators said they would block her appointment.

Russian diplomats appear to have breathed a sigh of relief when John Kerry was appointed secretary of state. As national security adviser, Russians will have few direct contacts with Rice. But still, they cannot be happy that someone with such a jaundiced view of Russia's role in the world will have the ear of the president when he designs and implements his foreign policy.

Rice's predecessor as national security adviser, Thomas Donilon, was overshadowed by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. A lawyer and lobbyist with no military or diplomatic experience, Donilon is credited with being a good manager who was able to keep tight control over the fractious bureaucracies involved in security policy. But it is hard to point to any prominent foreign policy achievements since Obama took office. The most pressing disappointment was Obama's inability to forge a consensus for action on Syria. The major accomplishment during these years was arguably the June 2010 UN Security Council resolution tightening sanctions on Iran, but it was Hillary Clinton who was credited with persuading Russia to support that action.

Samantha Power has been an important influence on Obama's foreign policy thinking. An Irish journalist and author, Power won a Pulitzer Prize in 2003 for her book, "A Problem from Hell. America in the Age of Genocide," in which she castigated the U.S. for failing to intervene in Rwanda in 1994. At the time of the Rwanda genocide, Rice was director for international organizations and peacekeeping at the National Security Council and thus one of the officials directly responsible for the inaction that Power so fiercely condemns. Journalist Julia Ioffe wrote in the New Republic in December that "Rice's foreign policy evolution has been that of a haunted realist reborn as an impassioned interventionist."

Obama, who was enamored by Power's book, tapped her as a foreign policy adviser during his 2005 senatorial campaign. After he became president in 2009, she was appointed senior director for multilateral affairs and human rights on the National Security Council, where she lobbied vigorously for more active intervention in humanitarian crises. Her most notable achievement was the enforcement of a no-fly zone in Libya in 2011, which turned into a military campaign for the overthrow of Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi. (For the past year, Power has been absent from the White House on maternity leave.)

The Libya campaign has become a pivotal case for Russia, illustrating the perfidy of the West and Washington's penchant for using military force without considering its long-term consequences.

Within the U.S., Obama's foreign policy has been under attack from all sides. Liberals are indignant about his increased use of drone strikes without congressional oversight, his record number of prosecutions against government employees for unauthorized leaks, and his failure to follow through on the promise to close the Guantanamo prison. Conservatives are making hay over the administration's alleged cover-up after the Benghazi attack. Obama's indecisiveness over Syria has provided more ammunition to critics who favor a more muscular intervention.

Given these constraints, it is unlikely at the end of the day that the appointment of the interventionists Rice and Power will result in a more assertive foreign policy. At the same time, however, it is highly debatable that Russia will somehow benefit from having a cautious and embattled Obama in the White House.

Peter Rutland is a professor of government at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.